當前世界政治與經濟發展的平衡,已然將歐美與亞洲之間的局勢重新洗牌,因此也為亞洲這塊後殖民的戰後大陸設定了新的文化與藝術話語。藝術拍賣會上,中國上層階級的精英競相把屬於自己的文物帶回祖國;在學術論壇與文化議題中,人們越來越常爭辯「歸還」的必要性――歸還那些殖民時期從亞洲、非洲、南美洲盜走的古董、文物、檔案與遺產,讓它們回到原來的出處。歐美各大博物館紛紛致力將亞洲當代藝術納入自己的收藏與展覽。事實上,許多亞洲富豪早在這些博物館的董事會裡取得席位,透過資金的挹注,推廣亞洲藝術,藉以調整館方蒐購作品的路線,好打造一個「國際藝術的門面」。不過,最重要的是,「立足本土平臺、加強文化價值」已經成為許多國家公私部門領導者關切的重點和政策。學界、機構與媒體都在想方設法,將國家與地方的藝術文化帶進研究與展覽。因此,當各地出現許多雙年展與藝術獎――用來表彰過去十年間的傑出創作者――也就不足為奇了。提到藝術獎,上海外灘美術館主辦的「Hugo Boss亞洲藝術大獎」(Hugo Boss Asia Art Award)、哈恩.內夫肯斯基金會與曼谷藝術文化中心當代藝術獎(Han Nefkens Foundation-BACC Award for Contemporary Art),以及新加坡美術館的「亞太藝術獎」(Signature Art Prize),被公認為所有的地方藝術獎當中最負盛名的三個。作為2015年「Hugo Boss亞洲藝術大獎」的評審與2018年「亞太藝術獎」的提名人,這三年來基於我對上述二獎的觀察和參與,見證了東南亞藝術,特別是越南藝術家,奇蹟般的崛起。2015年,菲律賓的女性藝術家谷口瑪麗亞(Maria Taniguchi),與中國、臺灣和香港藝術家一同入圍「Hugo Boss亞洲藝術大獎」的決審名單,最後脫穎而出,獲頒30萬人民幣的獎金;2016年,越南藝術家阮芳伶(Phuong Linh)贏得15,000美元的哈恩.內夫肯斯基金會與曼谷藝術文化中心當代藝術獎;2018年6月,「亞太藝術獎」高達60,000新加坡幣的獎金,發給了越南藝術家潘濤阮(Phan Thao Nguyen)。這樣的成就,讓越南在亞洲與全球的當代藝術版圖立下新的里程碑。

如果說,阮芳伶與潘濤阮獲獎的殊榮,可以提振越南在國際藝術舞臺上的民族士氣,那麼,趁著這股勁勢,我們不妨將視角調得更複雜、更批判一點:為什麼國際評審會選擇阮芳伶長達十年的計畫及潘濤阮的作品《熱帶午睡》(Tropical Siesta)?為什麼分別來自亞太與中亞各國的140多位藝術家入圍「亞太藝術獎」,最後被選進決賽名單的15件作品裡,越南與日本就各占了兩位?除了潘濤阮之外,「亞太藝術獎」決審的入圍作品展還包括了另一個越南藝術家聯盟「螺旋槳團體」(The Propeller Group)的《AK-47 vs. M16》――這個聯盟位於西貢,三名成員分別是安德魯.阮俊(Tuan Andrew Nguyen)、富南.沙哈(Ha Thuc Phu Nam)與麥特.魯賽羅(Matt Lucero)。

這幾件作品皆以歷史敘事作為故事的骨幹。在《熱帶午睡》裡,藝術家用一組雙頻錄像與X 光底片上繪製的油畫,創造了一個虛構的世界,其中的居民全是來自農村的孩子:他們上學、玩耍,重新搬演神職人員亞歷山德羅(Alexandre de Rhodes)的遊記。一般認為德羅創造了越南語的拉丁化拼音文字,但實際上並非如此,用羅馬字母拼寫越語發音的另有其他歐洲傳教士,但德羅編寫了第一部《越葡拉詞典》,賦予拉丁化的越南文一種科學定位。潘濤阮的錄像與油畫裝置中所暗喻的歷史也是虛構的,是一個模糊的灰色區塊,游移在眼見為憑、照本宣科,以及具體現實之間。

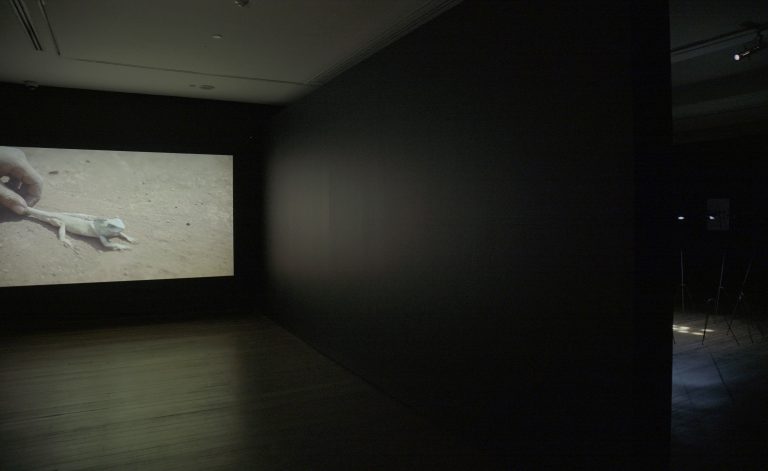

潘濤阮,《熱帶午睡》,2017,錄像裝置,「亞太藝術獎」決審入圍作品展。圖/潘濤阮提供

潘濤阮,《熱帶午睡》,2017,錄像裝置,「亞太藝術獎」決審入圍作品展。圖/潘濤阮提供

同樣是裝置,螺旋槳團體的《AK-47 vs. M16》包含錄像與雕塑。雕塑部分是一塊用在彈道測試上模擬肉體損傷的透明凝膠。那塊凝膠中有兩枚相互撞擊的子彈,分別射自兩款傳奇突擊步槍,一是由蘇聯研發的AK-47,一是由美國陸軍研發的M16。緊挨著雕塑旁邊的,是一件錄像作品,慢動作顯示一個在凝膠中延展的彈道測試,造成時間感的喪失。《AK-47 vs. M16》是一個關於「對峙」的深刻縮影;這個對峙在兩顆子彈之間,在兩種步槍的設計概念之間,在冷戰雙方的軍備競賽之間,也在越戰時期各自使用這兩款步槍的前線士兵之間。作品的實體呈現令人驚嘆,儼然將觀眾帶入歷史的神話世界裡。

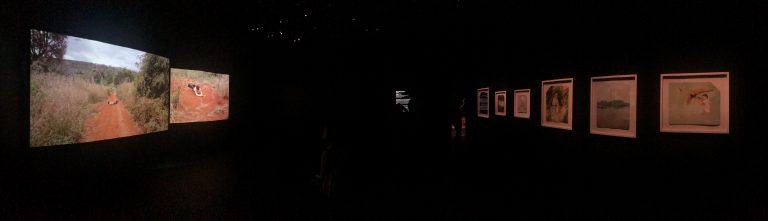

「無盡無視」展場一隅,阮芳伶獲得哈恩.內夫肯斯基金會與曼谷藝術文化中心當代藝術獎首獎之後,於曼谷藝術文化中心舉辦的個展。圖/阮芳伶提供

「無盡無視」展場一隅,阮芳伶獲得哈恩.內夫肯斯基金會與曼谷藝術文化中心當代藝術獎首獎之後,於曼谷藝術文化中心舉辦的個展。圖/阮芳伶提供

「無盡無視」(Trùng Mù-Endless, Sightless)一展羅列了多種美學的形式,講述這個國家的歷史與藝術家個人的身世。這是一段旅程,帶領觀者體驗光、聲、煙霧、動態的影像、靜態的雕塑以及取自越南中部高地的玄武岩土壤繪畫。這些作品透過後殖民故事、基督教在越南領地的擴張、被遺忘的記憶,以及時空意識中無可名狀的盲點,隱隱結合在一起。阮芳伶稱自己為「行旅藝術家」,不斷上路探索、學習、創作;或許,她心中所想的,是16世紀歐洲文藝復興藝術家的流動性,然而,她的旅程所反映的,實際上更像是一股驅力,敦促她去挖掘那些不及述說的無盡歷史,其中有著種種碎裂的現實和虛構,躺在塵埃、消亡的世代與平凡的社區之下。

我們不妨這樣看:潘濤阮、螺旋槳團體與阮芳伶的作品價值之所以持久,除了視覺的魅力外,主要還來自於歷史隱喻。

歷史隱喻在藝術裡並無新意。我指的不僅僅是當代藝術,看看越南的民間藝術――那些在1920年代河內的越南美術大學尚未成立之前的作品――當時的藝術家沒有名分,卻已在作品中使用許多的符號、民間傳說、神話與歷史故事。即便在越戰當中,無論是北越或是南越的作品,內容也經常傳遞某種政治信息,有些可能來自藝術家本人,有些來自政權當局。不過,1975年南、北越再次統一後,整個民族在藝術作品中所呈現出來的歷史,轉而偏向國家的視角。儘管風格、內容,甚至關懷或情感方面,仍然帶有個別藝術家的特質,但在多數例子裡,作品反映的歷史均屬人云亦云、隨聲附和的版本。越南的當代藝術發展自1990年代初,藝術家開始堅持用藝術來創造在野的歷史話語。當然,對於這種不符合官方說法的地下詮釋路線,政府/國家機制的因應之道,就是鼓勵風景、抽象或日常生活這一類先前才被他們斥為「資產階級」的題材。面對如此的責難,藝術家亟需揭示/創造歷史的多重面向,尋求被埋藏或遺忘的歷史片段。越南藝術家各憑本事,同時從形式和話語切入,以美學作為虛構歷史的手法,將過往的片段依照時序串成連續的敘事。

此類作品打開許多詮釋歷史的另類途徑,取代主流書籍或媒體中刻板的解讀。這股運動激勵了藝術家本身――讓他,或她,自覺像一個考古學者――同時也激勵了觀眾,更大大地挑起西方博物館與研究機構的興致,畢竟越南的歷史主要便封存於那場涉及越南與美國的戰事之中。因而,現在正是時候,讓國際的文化、藝術平臺以及國家機構與政府單位,都能認可當代藝術透過美學呈現微觀歷史的作用,並尊重其角色所含納的批判與人文價值。美學在這裡,並不僅僅意味著視覺上的吸引,另外還包括再現的政治,以及如何質疑或構成政治的歷史話語。

無論如何,「敘述或揭示歷史」不該是越南藝術的唯一路線。若只作為一種用來連結世界的獨特策略,越南藝術不過是一種政治宣傳的替代手法――假借邊緣類型的刻板印象,將自己包裝在理所當然的異國風貌裡。我們真正需要的,是一個多元的藝術生態,以及各式各樣關於硬體、教育和資金的支持。