相較於日本從百年前便萌生之妖怪學研究,臺灣直至近年才因中研院學者林美容的《魔神仔的人類學想像》開啟了從人類學、民俗學角度正視過往被視為「鄉野奇譚」的鬼妖民間傳說。接下來的文壇掀起了一瀾妖風:何敬堯、臺北地方異聞工作室、行人文化實驗室附屬妖怪研究室等創作者各由不同視野重新耕掘臺灣妖怪文獻與建構新論述,並進而發展出以妖怪為題材之小說、桌遊、電玩等相關文創產業,至2018年國立臺灣文學館策劃了「魔幻鯤島,妖鬼奇譚――臺灣鬼怪文學特展」,梳理了臺灣鬼怪傳說的流變與衍化,至此,往昔民間熟知的「林投姐」、「魔神仔」等鄉野傳說正式被納入臺灣歷史脈絡裡被討論與再現。

相對於文壇的妖怪流風,當代臺灣劇場上以民俗鬼怪為題材之創作卻仍屬少數,2013年,臺南「南島十八劇團」的《女誡扇》改編了日本作家佐藤春夫創作於1925年的《女誡扇綺譚》,這個短篇小說以臺南安平廢屋裡的靈異女鬼傳說為基底,營造出殖民地式「迷濛奇幻的異國浪漫」。1「南島十八」於臺南安平古蹟「樹屋」裡演出此作,在枝葉根莖亂布的廢屋裡呈現出詭譎的日臺文化混雜氛圍。而2018年「再現劇團」的《物怪之里》則以「理解妖怪,正是理解一套社會符碼與規則在一個族群『暗面』中如何運作最貼切的方式」2 這樣的角度切入民間原有妖怪傳說,如「椅仔姑」、「老猴魅」等,並延伸出從現代社會衍生之「怪」,如因河川汙染而產生變異的「石娘」、隱喻現代尼特族的「繭妖」等等,這個作品不探求民俗學脈絡下的妖怪傳說,而是藉妖討論「現代」帶給人類的影響。而同樣來自臺南的「雞屎藤舞蹈劇場」,從其介紹語「我們是雞屎藤,為各位帶來府城的故事」即知其作品多以府城及臺灣民俗、歷史與文學為素材創作:《府城仙怪誌》(2015)改編日治時期臺南作家許丙丁的文學作品《小封神》;《少女黃鳳姿》(2016)以日治時期少女作家黃鳳姿的生活及其筆下的臺灣民俗信仰為題;《府城夜話》(2018)則以臺南三則鄉野奇譚:〈陳守娘〉、〈洲仔尾白馬穴傳說〉與〈運河奇案〉3 等民間傳說為文本,「重新從田野調查、訪談、歌仔冊及民間紀錄裡尋找幽微故事之外的舞蹈紀實劇場」。4為聚焦於「臺灣妖怪」與當代的連結,筆者將以自身擔任雞屎藤舞蹈劇場編導之身分,在本文裡討論《府城仙怪誌》與《府城夜話》兩個作品裡的仙鬼妖,如何在混合後殖民與全球化脈絡之下重構「地方感」(sense of place)的創作策略。

臺灣歷經多重與連續殖民政權5,到了1980年代政治解嚴後,臺灣的解殖民工程才正式開始起步,政治上、藝術上的本土運動風起雲湧,然而對於何謂「臺灣文化」卻一直處於變動的歷程。6 到了2019年的當下,除了尚未完成的「心靈的去殖民」7,當前面對的更是混合了資本主義擴增下的「全球化」(globalization)現象,在當代的都會生活中,我們逐漸失去「地方感」,也使得「地方感的重建」(re-establishing sense of place)成了草根組織行動抗衡全球化的重要策略。8 除了各地方的古蹟保存、都市再造、社區總體營造等的推行,「劇場的展演在地方感的再現與重塑又扮演了何種角色?」9

從「民族舞團」起家的「雞屎藤舞蹈劇場」,藝術總監許春香早年在學校裡教授民族舞蹈。在臺灣戰後的舞蹈教育裡,所謂的「民族舞蹈」指涉的是涵括在「中華文化」大傘之下,強調五族共和(漢滿蒙回藏)的中國地方舞蹈,「臺灣」則被視為是「地方舞蹈」的一環,在表演裡多以「混搭式原住民舞」或帶著鄉村風情的「臺灣農村與廟會舞」呈現。從2007年以臺南林百貨及家族回憶為素材的《昭和摩登.府城戀歌》開始,雞屎藤開始尋找能呈顯臺灣舞蹈其它面向的劇場型態與美學,從題材開始,涉入更多元的臺灣時代;從身體質地的重建開始,尋找在多重文化影響之下,帶著「臺灣氣味」的身體呈現方式,試圖以具「地方感」的舞蹈面對全球化下的文化定位模糊。

一、在府城仙拼仙

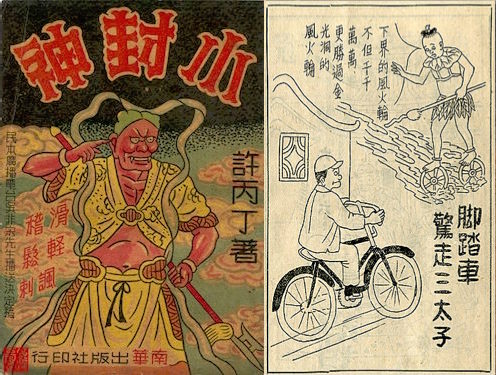

《府城仙怪誌》首演於2015年,是雞屎藤「文學舞蹈劇場」10系列製作之一,以府城著名文人許丙丁(1899–1977)創作之白話章回小說《小封神》為素材改編,並於臺南延平郡王祠作環境劇場展演。奠定許丙丁創作特色的《小封神》於1931年首刊於日治通俗報刊《三六九小報》上,許丙丁以筆名「綠珊盦主」發表連載至1932年為止共24回。許丙丁將此書自題作「滑稽童話」,他以詼諧、諷世筆觸描寫日治時期府城三宮三廟、正神偏神之間發生的爭端趣事,「是臺灣第一部正式發表兮漢字臺語小說」11,亦是第一本以府城寺廟神佛為主角的白話小說。

許丙丁《小封神》漫畫書影 (楊燁先生收藏與攝影)

許丙丁《小封神》漫畫書影 (楊燁先生收藏與攝影)

更加趣味的是,《小封神》並不僅僅是個虛構架空的「奇幻文學」作品,作品中亦具有鮮明的「時代性」與「在地性」。首先是小說的背景時空設定於1930年代的府城,其中所提及的神仙議會、人口節育、自轉車(腳踏車)比賽驚走三太子、雷震子與飛行機較量等情節,皆反應了日治時期臺灣現代化過程的軌跡。1930年代正是日本殖民臺灣的中晚期,「現代化」對臺灣而言不僅指涉的是來自西方的事物,也是經由日本明治維新後的「亞洲式現代化」,「現代性」(modernity)因此作為在日本殖民過程中,顯示殖民者優位位置的重要工具之一。在許丙丁的《小封神》裡即可見到他藉神佛對於民間迷信的抨擊,亦能觀察到日治後受到「殖民現代性」影響的知識分子筆下對於「現代/傳統」、「先進/落後」的價值觀。

此外,許丙丁諧擬了中國神話經典《封神演義》的文體,卻將其作「在地化」的改編,不僅是故事中出現的人物皆為府城考察有據的當地信仰神尊,故事中的地理空間亦被置於日治時期的臺南。故事的開始即是位於臺南「赤崁東街」之小上帝廟(即「開基靈祐宮」)派遣部將去到「打銀街」的「同裕當鋪」典當通天冠以換取銀兩展開整個故事,「打銀街」這個名稱始自清代,即指稱今臺南忠義路一帶因銀樓商家群聚而產生的街區。除地景的敘述之外,許丙丁亦挪用了許多原有民間傳說,並鑲嵌在《小封神》的架構之下,例如臺南目前置於赤崁樓以及在保安宮裡被奉祀的十隻乾隆御賜石贔屭,即分別化身為小說中的「龜靈聖母」與其徒眾們。

許丙丁的原著故事情節錯綜複雜、登場人物繁多,因此雞屎藤的改編策略即是聚焦於小說中所呈顯的「地方感」與日臺文化混雜的「時代性」。我們在改編過程中加入了一個原著中未出現的角色――日治時期「末廣公學校」(今進學國小)的少女りんご(蘋果),另外亦加入布袋戲的演出,以布袋戲擅長之唸白演繹許丙丁以常民式文白交雜的臺語寫成的文字,亦以布袋戲「寫意、象徵」的表演特色對應原著裡虛實交雜的敘事。故事從蘋果在放學途中遇到1945年臺南大空襲時,在古老中藥店裡避難遇到戲偶三太子開始,讓戲偶三太子帶領主角進入許丙丁筆下虛構的神怪世界,亦是透過日治少女的視角,看見許丙丁的小說裡帶著府城在地性的民俗與神妖。

《府城仙怪誌》中的主角りんご(蘋果)與戲偶三太子,2018。圖/韓政宏攝影

《府城仙怪誌》中的主角りんご(蘋果)與戲偶三太子,2018。圖/韓政宏攝影

《府城仙怪誌》於廟口古蹟呈現,期待讓觀眾感知歷史建築、故事與當代的連結。圖為延平郡王祠,2015。圖/韓政宏攝影

《府城仙怪誌》於廟口古蹟呈現,期待讓觀眾感知歷史建築、故事與當代的連結。圖為延平郡王祠,2015。圖/韓政宏攝影

除了透過原著裡的文字勾勒出屬於府城的「地方感」,雞屎藤亦運用劇場元素建構府城意象:展演空間多選擇於廟口古蹟呈現,如臺南延平郡王祠、楠西北極殿與臺北孔廟,各具特色與歷史意義的廟宇空間原本即是具文化性的空間,亦是許丙丁原著裡所有事件的發生舞台,這樣的展演型態不只是一個作品的展現,而是讓觀者重新「看見」歷史建築、故事與當代觀眾的連結,「觀演者則透過觀劇中身體與空間的感知,感受這些消逝的地方記憶在當下的意義」。12 而在劇中仙妖的形象上,亦反轉過往「民族舞」慣有的華麗、亮片古裝風格,而是混合日、臺、漢文化的呈現:如主角蘋果身著日式公學校學生制服;劇中反派「馬扁禪師」則身著漢服、戴墨鏡、留日本式長髮,呈現猶如臺灣戰後初年「胡撇仔戲」(Opera) 13 的風格;金魚、鹿角兩仙以武俠片裡中國道士的形象登場;龜靈聖母則以「男扮女裝」穿著傳統民族舞的華麗服裝呈現帶點「酷兒」意味的形象;而十隻贔屭精則參考了臺灣民間車鼓陣表演者頭戴大花、身著花布衣的打扮。

《府城仙怪誌》從情節、地點到服裝的混雜文化呈現其實也演現了臺灣劇場從傳統過渡到現代的歷程,而這段歷程所對應的亦是臺灣當代的後殖民(post-colonial)情境――多重與連續殖民的軌跡在文化、藝術與社會各層面留下深切的痕跡,亦構成了當代臺灣文化混雜的面貌,因此這個「雜匯(hybrid)文化」的展示也被我們視為是建構臺南「地方感」的方式之一,儘管它其實是懷舊的(nostalgic);儘管各文化之間的權力關係需被更清晰地梳理。

馬扁禪師」身著漢服、戴墨鏡、留日式長髮,呈現臺灣戰後初期的「胡撇仔」風格;金魚、鹿角兩仙則以中國道士形象登場,2018。圖/韓政宏攝影

馬扁禪師」身著漢服、戴墨鏡、留日式長髮,呈現臺灣戰後初期的「胡撇仔」風格;金魚、鹿角兩仙則以中國道士形象登場,2018。圖/韓政宏攝影

《府城夜話》裡的直播主與陳守娘,2018。圖/韓政宏攝影

《府城夜話》裡的直播主與陳守娘,2018。圖/韓政宏攝影

二、府城鄉野奇譚裡的「地方」

打破過去改編臺灣文學作家文本為舞蹈劇場的模式,首演於2018年的《府城夜話》則以「事件」為文本,以「紀錄劇場」的概念重新演現三個發生於府城的鄉野奇譚:〈陳守娘〉、〈洲仔尾白馬穴傳說〉以及〈臺南運河奇案〉。根基於「事件」而非「文學」,劇中考據了不僅是過去常使用的文字資料,亦加入口述歷史、田野調查、媒體報導、學術研究、甚至是網路文學的當代詮釋,尋思在剝除了「傳說」的外衣之後,我們能從這些鄉野傳說裡看到什麼樣的府城過去?而這個過去又如何被當代的我們認知?

我們在表演裡加入了一位「網路直播主」,在演出現場以「直播」為表演模式,觀眾大部分時間僅能透過投影在一破屋上的影像看到直播主的表演與互動,而飾演直播主的演員則現場在破屋內對著鏡頭演出,並現場配合場上表演者的行動。網路直播是近年來新興的媒體型態14,我們以直播主的視角作為觀看這些鄉野傳奇的當代觀點,因此整個演出不僅呈現事件的原委,更透過直播主的口白帶領觀眾探尋構成這些傳說的多元觀點。

《府城夜話》〈陳守娘〉劇照,2018。圖/韓政宏攝影

《府城夜話》〈陳守娘〉劇照,2018。圖/韓政宏攝影

〈陳守娘〉為臺灣三大奇案之一15,為府城名氣僅次於林投姐之女鬼。其故事的記載可上溯自劉家謀《海音詩》以及連橫《臺灣通史》,陳守娘傳說在2013年「PTT」網站的「Marvel版」16上,因網友Kokone以幽默與當代化的口吻重述了這個傳說後而再度聲名大噪。在這個版本裡,陳守娘居住於今臺南東菜市一帶,年少守寡,被婆婆與小姑設計後被虐致死並埋在山仔尾(今南門路一帶),死後魂魄含怨大鬧府城,與有應公、永華宮的廣澤尊王與德化堂的觀音大士等府城神明交鋒。我們帶著舞者們在臺南踏查陳守娘故事裡的足跡與廟宇後,察覺在清代的陳守娘其實是典型身處多重壓迫(國族、性別、甚至是死後面對的神權)下的臺灣漢人女性,然而這位女性並未如現實中許多受害女性一般在死後即被遺忘,而是挺身為爭取自己權益不惜挑戰位階更高的神明們。可憐當時臺灣女性唯有透過民間傳說裡「女性厲鬼」的復仇得以為自己一吐長期被多重壓迫之氣,這些女性厲鬼或可被視為被壓迫底層女性的潛意識之魂。為翻轉原始故事裡女性厲鬼的可怖形象,我們選擇讓五位表演者皆成為陳守娘的分身,這也意謂著其實過往有類似遭遇的女性並不僅一位。整段創作並不著重於陳守娘的幽冥形象,而是將祂如何從被壓迫引發憤怒而成為厲鬼挺而造反的過程,以舞者在理解了整個事件背景後所生長出的「動作譜」(score)為這段演出加上了「臺灣與臺南性」。

《府城夜話》〈洲仔尾白馬穴〉劇照,2018。圖/韓政宏攝影

《府城夜話》〈洲仔尾白馬穴〉劇照,2018。圖/韓政宏攝影

〈洲仔尾白馬穴〉則是一則與風水地理有關的傳說。民間傳說清代義民首領鄭其仁17墓(相傳亦是明鄭時期鄭成功與其孫鄭克塽之墓)墓前的兩匹石雕白馬因得到墓穴風水靈氣幻化成精怪,常在半夜踐踏農田偷吃作物,村民不堪其擾設下陷阱,並順著綁在陷阱上的紅線找到罪魁禍首――墓前那對石馬,而後合力將兩匹石馬的前腳鋸斷。像這類物件成精怪的傳說不僅出現在臺南洲仔尾,基隆和平島的西班牙城堡、臺南海安路、屏東東港崙仔頂以及臺中葫蘆墩也都出現過白馬精現身守護寶藏的傳說,除了白馬之外,亦有白銀幻化為白雞、白兔等動物的傳說於臺灣各地出現。18物件因歷久而成精怪的傳說亦出現於日本與中國《聊齋誌異》這樣的小說裡,然而「得地理風水成精」與「守護特定人物的墓穴或寶藏」為這樣的物件精怪賦加上「地方性」色彩,如基隆和平島守護西班牙城堡寶藏的白馬精故事所對應的正是臺灣北部曾被西班牙攻佔的過去。因此,我們在這段的呈現加上了洲仔尾被斷腿石馬的身體特性,並從石馬的石頭質地發展出身體特性與動作譜,期待能以地方故事生長出具「地方感」的身體。

根據王婉容老師歸納印裔英國學者霍米.巴巴(Homi K. Bhabha)對於後殖民劇場的論點,提到:「劇場展演一向是文化論述辯證與演繹的場域,也是意識型態積極創造意義的空間。這個不屬於任何特定身分認同的「中介空間」(liminal space)中,有如不固定的過渡或轉換的介面,所有社會上習以為常的習慣與想法,隨時準備重組成全新的意義」。19 在後殖民情境下對「臺灣文化」的追尋與抵抗全球化的「地方感」的重構上,自解嚴後已在社會各個領域累積不少成果,而2010年後在劇場上「臺灣妖怪」或「鄉野奇譚」的萌發也許正是在劇場這個「中介空間」裡對於臺灣文化「主體性」另一種面向的追尋。「神鬼妖」並不存在於物理世界的認知裡,而與劇場同樣是處於「之間」的某種存在,因此「臺灣神鬼妖」也正是在劇場這個可轉繹與創生意義的第三空間裡得到另一種被詮釋與再現的角度,而這個角度是否可能亦構成當代臺灣在面對全球化之時能再次確認自己、面對未來的方式?