“Shooter.cn,” the largest subtitles website in China, declared permanent closure in 2014. A couple of hours earlier on the same day, “YYeTs.com,” a website that enjoyed a stellar reputation of subtitles translation as well, announced that it would cease operations for an indefinite period. These announcements were then widely believed to portend the end of fansub groups. Many people began to indulge in a wistful nostalgia for the changes induced by fansub groups, as if these groups have passed into history. In fact, on the contrary, fansub groups still exist today, and they appear even more pluralistic in terms of structure, subject matter, operation, and circulation.

Fansub groups have played an ambiguous role in the circulation of films and TV dramas. They’re often equated with copyright infringement from a legal point of view. However, their operations are based not so much on stereotypical piracy as on non-profit altruism. The modus operandi of such unofficial circulation has become an open secret under the media and scholarly spotlight. Observing this phenomenon from a wider angle, we may notice that this sort of unofficial subtitling is not only rampant in the circulation of films and TV dramas, but also as implication-laden as multifaceted.

The availability of audiovisual products is the basis for fansub groups. Having a continued presence in China, Brazil, Italy, Spain, and many native English speaking countries, fansub groups primarily process the texts of animations, dramas, and documentaries. By virtue of their members’ collaborative efforts, these geographically widespread fansub groups have enabled many audiovisual works that are not released in their own countries to circulate domestically, which not only reflects the imbalance of power in the worldwide communications network, but also indicates the conflicting needs between the global and local transmission. Chinese scholar MENG Bingchun argued that fansub groups in China lie somewhere in-between governmental regulations and commercial competition, and they tend to cause disturbance to the worldwide communications network. Harnessing the power of experience and knowledge they acquired from collaborative endeavors, fansub groups, along with the process of re-transmission (or disturbance), have not only challenged the concepts of copyright and fixed text, but also blurred the boundaries between the local and the global, commerce and commons, as well as between consumption and production.1 In addition, Brazilian scholar Vanessa MENDES MOREIRA DE SA illustrated her point with the example of the fansub group for the American TV series Lost,2 arguing that this kind of unofficial communications networks has supplanted official ones to some extent, altered the hierarchical structure of the worldwide communications network, and liberated the media circulation from the permission culture3 by granting it considerable freedom. The abovementioned studies seemed to take a positive view on fansub groups. Nonetheless, this mode of unofficial communication simultaneously strengthens the already advantageous westernized texts and their inherent commercial logic, which is nothing if not paradoxical. To put it another way, the communication mode of fansub groups is seemingly anti-western, yet the advantageous contents they circulate may instead facilitate occidental countries’ ideological dominance4 and niche marketing in the mainstream market. MENG Bingchun further pointed out that fansub groups in China have challenged (or disturbed) the worldwide communications network, but they’re far from a menace to Chinese politics.

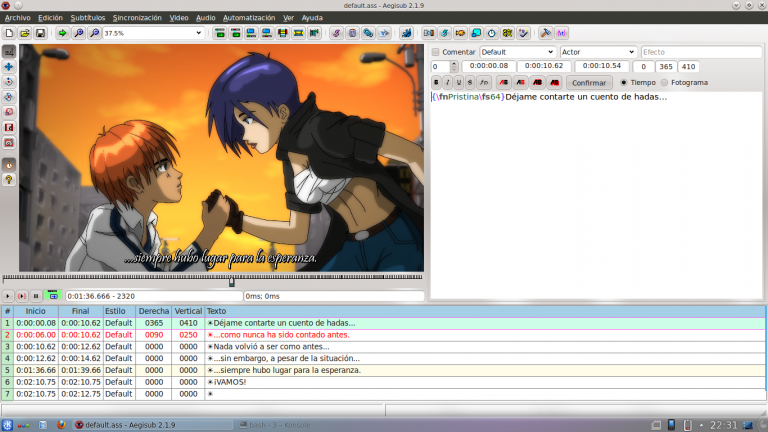

A simulation of subtitling with the software Aegisub. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

A simulation of subtitling with the software Aegisub. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Apart from the macroscopic dimension, the operations of fansub groups also act as a focal point. More specific, the operations of fansub groups can be construed as a manifestation of the participatory culture—aficionados (fans) collaboratively translate subtitles through their collective wisdom. Such division of labor is often indicated in the opening titles of the films or TV dramas they circulate, mentioning the proofreaders, timeline producers, and translators of the subtitles. The members undertake this sort of joint endeavors for a variety of motives—personal passion, burning enthusiasm for texts, gaining the sense of achievement from seeing their own works circulated online, or increasing their own language proficiency. Personal motives are thus transmuted into organizational practice, which can be encapsulated by the concept of “altruistic engagement in affective labor” formulated by Kelly HU.5 Nevertheless, the competition among different fansub groups is so intense that their code of practice is every bit as strict as that of ordinary occupations. For instance, they offer orientation and training to novices, and sometimes arrange interviews about the candidates’ acceptable workload per day/month, language proficiency, and related technical abilities. Besides, the operations of fansub groups are fairly hierarchical. The administrator of a fansub group is entitled to determine which member can process the latest contents and receive rewards as encouragement (in the form of virtual currency). Senior members often have greater access. To take a telling example, “Legenders,” the largest fansub group in Brazil, consists of more than 30 teams. Its administrator has the authority to assign tasks according to the team’s expertise and educational background; that is, to dictate which team is responsible for popular TV dramas, and which for less popular ones. Its administrator imposed a stringent set of rules, quality requirements, and strict deadlines by which the participating teams should abide. In other words, the criteria set by its administrator for disciplining its teams resemble those in ordinary occupations, serving to ensure its quality, competitiveness, and reputation. The inherent paradox of this mode of unofficial communication also finds expression in such code of practice.6

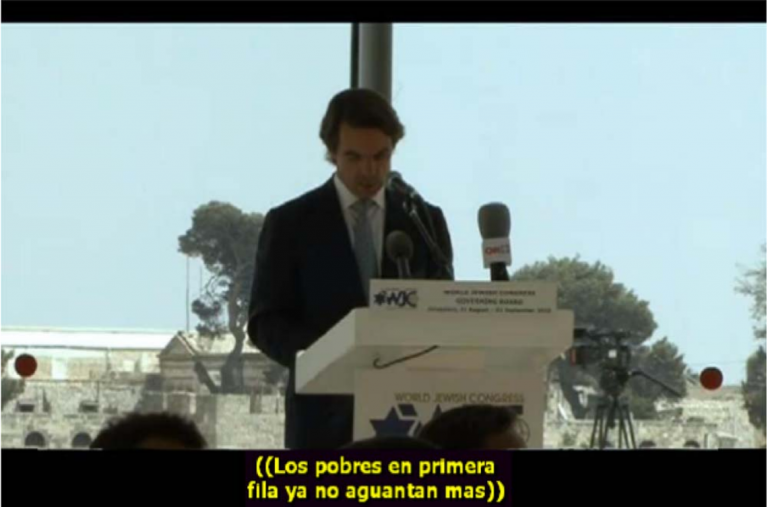

“The poor audience in the front row can’t stand it anymore.” The fansub group added the subtitles between the lines of the speech delivered by the Prime Minister of Spain. Photo provided by LIN Yu-Peng

“The poor audience in the front row can’t stand it anymore.” The fansub group added the subtitles between the lines of the speech delivered by the Prime Minister of Spain. Photo provided by LIN Yu-Peng

Kelly HU additionally showed that the operations of fansub groups in China represent a tug-of-war among copyright protection, governmental censorship, and unofficial networks. The dynamics therein is not so much total suppression as a state of fluctuation, to which the black-or-white logic doesn’t apply. For instance, fansub groups oppose pirated use of the subtitles they translated for profit, and equate piracy with theft. Besides, official communications networks may seek cooperation with fansub groups for their excellent quality and reputation, such as the cooperation between TSKS (a fansub group in China) and iQIYI (a Beijing-based online video platform), the conscious tolerance showed by legal video platforms towards the subtitles translated by volunteers of all stripes, and the news heard from time to time that fansub groups succumbing to the temptation of commercialization. This list is not exhaustive.

The majority of literature on this subject focus mainly on popular audiovisual products (e.g. Japanese, American, and British films and TV dramas) and the culture of fansub groups. As a matter of fact, the operations of fansub groups are not confined to the texts of mainstream audiovisual products, but proceed in a segment-based fashion. There are various fansub groups coping with different types of texts such as those of less popular films, soccer games and related events (Manchester City fansub group), as well as those having clear political agenda.

Breaking away from communication studies and cultural studies that give prominence to the role of fansub groups, Luis PÉREZ-GONZÁLEZ, a professor of translation studies, provided an alternative perspective of analysis—the political agency of subtitling (groups). He regards this kind of non-professional / amateur translation as part of civic engagement,7 and terms it “activist amateur subtitling,” a means for modifying or reversing mainstream narratives and producing alternative values as an interventionist strategy for resistance, insofar as to exercise civil and political rights.8 To clarify his point, PÉREZ-GONZÁLEZ systematically analyzed the political agency of “Ansarclub,” a fansub group in Spain. It had carried out a total of 27 subtitling projects between 2006 and 2010, principally on foreign TV programs that were not broadcasted in Spain, such as BBC’s HARDtalk, Al Jazeera’s news programs, and those deliberately ignored by mainstream media.

Drawing on the features of the digital culture, PÉREZ-GONZÁLEZ adopted a three-pronged perspective in his analysis; to wit, participation, remediation, and bricolage. There is not much difference between the perspective of participation here and the previously mentioned aficionados’ collective subtitling. Both serve as a mechanism for solidifying affection and identity, except that the former’s identity carries political implications. Remediation and bricolage are the very core of PÉREZ-GONZÁLEZ’s argument. In the process of remediation, fansub groups challenge the orthodox interpretations of existing texts with their own translation, aiming to reverse the unilateral narratives constructed by mainstream media. In one instance, Ansarclub intentionally added dramatic irony and provocative remarks between some lines of the speech delivered by the Prime Minister of Spain. Bricolage, by definition, is to reconfigure news or related image contents and put them into circulation. For example, a member of Ansarclub edited the contents of mainstream and far-right media, and in turn posted the edited contents on his personal website in order to satirize these media. Meanwhile, he made these edited contents freely accessible and usable to the public. Apart from quasi-organization political fansub groups, PÉREZ-GONZÁLEZ also highlighted the agency of individual subtitling, which is exemplified by the political satire videos with adapted subtitles commonly seen on YouTube. Profound significance of political resistance thus arises from the combination of existing materials and adapted subtitles. PÉREZ-GONZÁLEZ happened to cite the example of a Taiwanese YouTuber who adapted the lines of an episode of SpongeBob SquarePants to satirize China. The YouTuber thereby lodged a political protest against China and demonstrated personal agency of political resistance.

Maintaining a low level of participation, Taiwan is by and large a receiver of fansub groups’ output. Much to our surprise, PÉREZ-GONZÁLEZ’s analysis of political subtitling fits in with the Taiwanese context. Although quasi-organization political fansub groups remain wanting in Taiwan, individual agency has become the order of the day on the Internet, which is embodied in the videos (foremost Der Untergang) with satirical subtitles, and in the attempt to facilitate the circulation of the international news that were not broadcasted in Taiwan by adding Chinese subtitles to them (e.g. Al Jazeera’s reportage about Taiwan). The amateur / non-professional subtitling as civic engagement has opened up new horizons for fansub group studies, helping this discipline leave the confines of aficionados’ collaboration and the texts of films and TV dramas.

“Bullet-screen comments” refers to real-time comments from viewers flying across the screen like bullets. Photo credit: Creative Commons; designer: HSIAO Yanghsi

“Bullet-screen comments” refers to real-time comments from viewers flying across the screen like bullets. Photo credit: Creative Commons; designer: HSIAO Yanghsi

Each fansub group, whether political or not, serves a particular purpose (e.g. cultural communication or political identity construction), and meanwhile performs the functions of mediation and values promotion. In addition to these quasi-organizational fansub groups and individual aficionados, bullet-screen comments (or barrage commenting) constitute an alternative form of unofficial subtitling. The term “bullet screen” originally refers to the continuous firing of a large number of guns in a particular direction, or an artillery barrage over a wide area. Today, it has been used in denoting real-time comments from viewers (especially of animations) flying across the screen like bullets. Bullet-screen comments can be sent by viewers to the video platforms in real time. They appear from all directions rather than at the bottom of the screen like conventional subtitles. They move in all directions on the screen, which is reminiscent of a dense net of gunfire. Originating from the Japanese website “Niconico” and later appearing on Chinese ones (e.g. “Acfun,” and “bilibili” in particular), bullet-screen comments have become an audience favorite.

The purpose of bullet-screen comments is to allow the “direct” display of viewers’ criticism on the texts, while this communication mode ingeniously mirrors the relationships among viewers (or aficionados) as well as between viewers and texts (videos). Despite everything, viewers have mixed feelings about bullet-screen comments. On the one hand, these comments obviously interrupt the smooth flow of videos. On the other hand, viewers may find delight in reading them, hence a strengthened collective identity among aficionados. This communication mode has in turn redefined the relationships between viewers (or aficionados) and the texts in point. Daniel JOHNSON compared bullet-screen comments to counter-transparent subtitles.9 They are counter-transparent because viewers need not fully grasp the contents or other viewers’ comments, which may lead to erroneous or schizophrenic interpretations. Xiqing ZHENG held that this mode of communication and interaction is sometimes illogical. Specifically, bullet-screen comments are not necessarily based on mutual understanding but on complex wordplay, symbols, subcultural jargon, slang, and non-standard characters at times.10

ZHENG further pointed out that bullet-screen comments are the otaku subculture incarnate, and they represent a new mode of viewing. Distinct from ordinary video platforms (e.g. YouTube) that afford passive viewing only, bullet-screen websites created a space exclusively for otaku. Viewers can derive pleasure from the narratives of bullet-screen comments, hence a stronger sense of belonging. To put it another way, bullet-screen comments per se are as much a performance as a multi-task activity. Each of these comments must respond to the video contents and interact with other aficionados (and their comments) at the same time. Daniel JOHNSON terms it the “pseudo-synchronicity” that produces a feeling of live viewing via a sense of virtual time shared between viewers, as if they would collectively express their feelings and share their humor, sorrow and passion at the climax of the text in any specific moment. Going beyond oral communication, this phenomenon not only solidifies aficionados’ collective identities, but also creates a spectacle. In fact, bullet-screen comments have the potential for facilitating the alternative socialization and becoming a new mode of communication. Different from fansub groups though, bullet-screen comments have opened up new possibilities for the connection between aficionados and texts with its formal peculiarity.

These modes of unofficial communication, including films and TV dramas fansub groups, political fansub groups, and bullet-screen websites, have occupied vital roles in the worldwide communications network, although they are not necessarily able to challenge or shake the mainstream culture and the dominant communications network. Notwithstanding the fact that these modes of unofficial communication chiefly involve unauthorized audiovisual works and arouse the concern over copyright infringement, we shall never overlook their existence. Individual aficionados have also enriched the subculture of fan subtitling, exhibiting a captivating scene replete with audiovisual circulation and interaction.