In the past half-century of cultural development in Taiwan, “Indigenous peoples” have often been the object of desire for mainstream ethnic groups. “Desire” in this case is of course intertwined with complex scenarios (and sentiments?): at the highest level, it involves the mechanisms of governance of the modern state, and at the minimum, it seeps into the intimate structures of emotion and desire, with various enigmatic twists which can only be intimated, but not verbally conveyed. In the queer perspective that I take to the extreme, I even teased that the recent resurgence of “hunter aesthetics” as a new form of indigenous worship. But what I am more curious about is whether there is any element of eroticism in the way men in modern civilization gaze, admire, and pursue the foreign tribal men in pre-modern cultural systems. It would be much too fascinating if that were the case. In any case, this kind of scenario (sentiment?) is not an isolated case in the nearly half a century in Taiwan. Various types of love, admiration, and lust for pre-modern imagery from the standpoint of modern civilization are constantly alienated in knowledge production of art and literature, vividly beast-like, everchanging in guise.

If we weren’t so quick to engage with the issues of power and ethics in a post-colonial context, we have a situation that I find very appealing. However, in all guises of “desire”, the mode of desire among gay men goes straight to the point, rarely with any pretense; in the development of literature and art, “Indigenous men” are often the objects of desire for Han Chinese gay men. For example, in the literary field, CHI Ta-Wei has written at length in A History of Gay Literature: The Invention of Taiwan (2017). What I look into is why and how those “Indigenous men” became “our” objects of our desire.

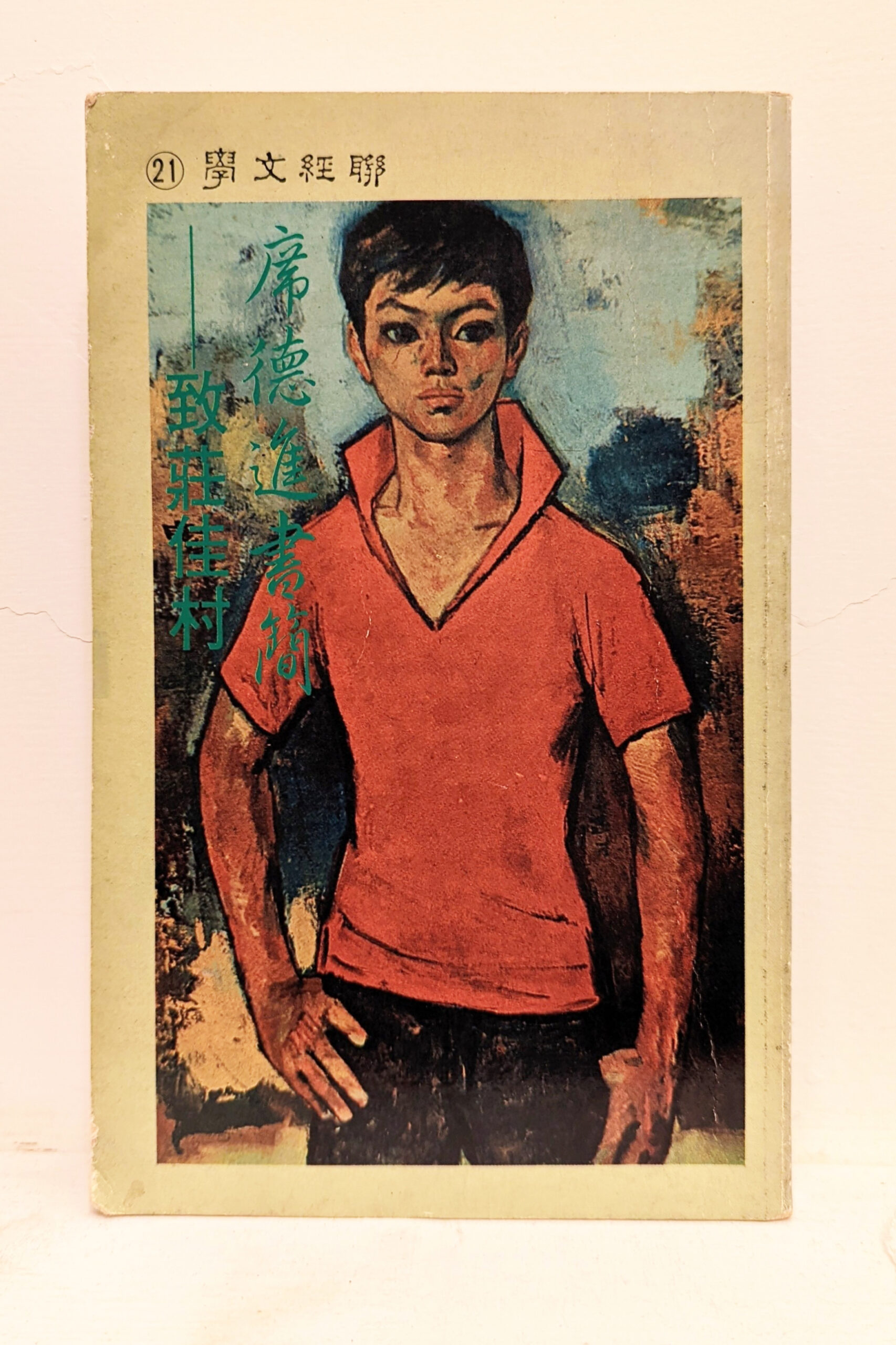

The creation of some kind Indigenous male symbol rich in the gaze of homosexual desire through literature wasn’t just found in the writings of PAI Hsien-Yung and YANG Hui-Nan. There was early precedent in art history of indigenous male figures being associated with certain “qualities” that relate to queer desire. For example, SHIY De-jinn discusses CHUANG Chia-Tsun, the prototypical subject in his painting Boy in Red, writing in Brief Notes from SHIY De-Jinn to CHUANG Chia-Tsun (1982), that CHUANG featured a “wild appearance of a highland tribesman”1. Whether CHUANG Chia-Tsun is truly a highland tribesman is beside the point; what matters is that the “wild look” CHUANG embodies, akin to that of a highland tribesman, is what SHIY finds captivating.

So what exactly is a “wild look”? If we trace back in the genealogy of “wildness”, we will find that this kind of appreciation and pursuit of pre-modern “wild” imagery from the standpoint of modern civilization had deep roots in early aesthetics. In the 18th century, Denis DIDEROT, a master of the French Enlightenment, considered the “barbaric” culture of exotic tribal societies, not comprehensible to the European society (then), has a certain “poeticism”2 capable of dispelling the pretensions of Neoclassicism. This barbaric culture is certainly a complex body of symbolism and imagery. Subsequent Western painters have repeatedly looked to the artistic and cultural landscapes of the pre-modern scene, taking them as stylistic guides, drawing closer the relationships between novelty and visual art, opening the way for myriad forms of gaze and appropriation towards the scenes of the “barbaric” and its aesthetics in the history of art for the next hundred years.

In Taiwan in the last century, the gaze of literary scholars and artists on the “wild” began to take on an erotic significance through the eyes of gay men. The depiction of Indigenous men in PAI Hsien-Yung’s Crystal Boys (1983) highly eroticizes the visual meaning of “wild”. According to CHI Ta-Wei’s research, there are two possible descriptions of Indigenous males in Crystal Boys: one is the primordial man Ah Hsiung, with “muscles on the chest hard as iron”; the other is Tieh Niu3, who gave an “art master” a sense of the “primitive life on the island” and “arresting natural beauty comparable to a typhoon or tsunami”. Here, the literary scholar directly interweaves the two masculine images, interposing the masculine body and the beauty of nature; “wild” is transformed from a rhetorical reference to the pre-modern state and the aesthetics of the earth, to become attached to a specific male paradigm, and begins to be sexualized and eroticized–in the eyes of the lustful gay man.

SHIY De-Jinn, 1982, front cover of Brief Notes from SHIY De-Jinn to CHUANG Chia-Tsun. Linking Publishing Co., Ltd.

SHIY De-Jinn, 1982, front cover of Brief Notes from SHIY De-Jinn to CHUANG Chia-Tsun. Linking Publishing Co., Ltd.

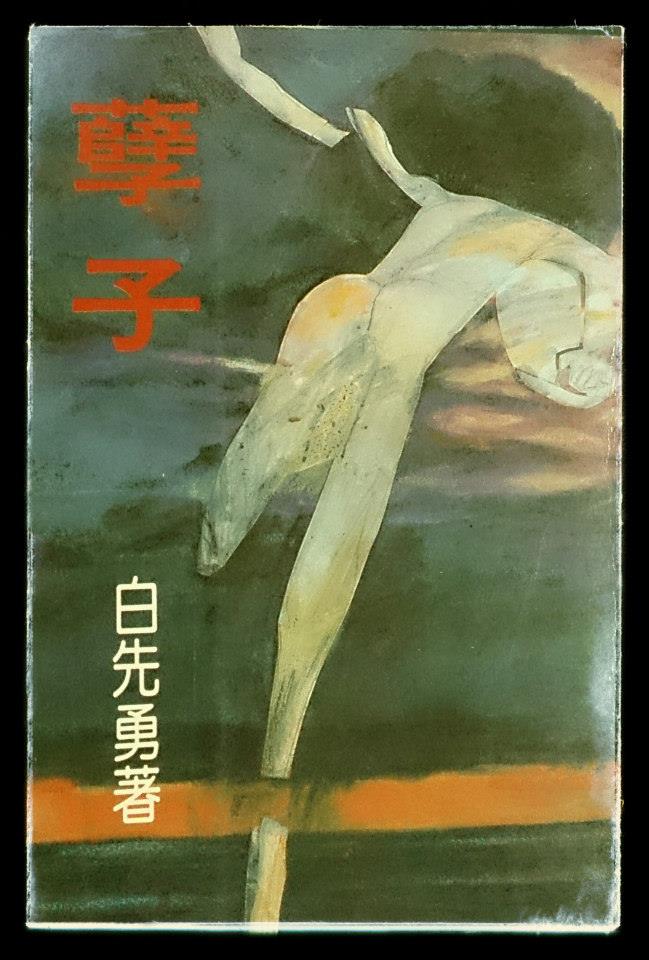

PAI Hsien-Yung, 1983, book cover of Crystal Boys. Vista Publishing.

PAI Hsien-Yung, 1983, book cover of Crystal Boys. Vista Publishing.

In the previous examples, Indigenous men were purely as objects being depicted. Gay men symbolize the desire of the queer subject by dissolution of the historical significance and sexualizing the Indigenous man; in this structure of desire, the queer is proactive, while the opposite for the Indigenous man. However, later in the 1990s and 2000s, the subjectivity of the Indigenous finally began to manifest itself in the literary field through writing. At that time, the development of Indigenous literature was highly related to the cultural thinking of the post-martial law period. Through media technology and spiritual strategies of several male intellectuals, a vigorous promotion of Indigenous literature and cultural development had quite early on anchored the term “mountains and coasts (shanhai)”4 in the sea of consciousness for the aesthetic context of the pan-indigenous ethnic group (for example, through the Taiwan Indigenous Voice Bimonthly magazine, founded in 1993 by key indigenous intellectuals and heavily promoted Indigenous literature and culture development. This launched the indigenous genealogy of aesthetics that springs forth from that symbol.) However, in this genealogy of the signifier, what kind of men have been represented by these largely male Indigenous writers? Let me set aside this big question for the time being. But in in a dangerous way, I do not think that they are absolutely situated at the other end of the aesthetic paradigm of queer desire.

In the contemporary art scene, Indigenous artists similarly emerged in the 1990s, in tune to the literary scenes of that time, based on the quest for their cultural subjectivity and the fact that most of the activists were men. In terms of technology and media, the biggest difference between artistic and literary creation lies in the fact that there is a process of visualization in art. To a certain extent, the aesthetic image of “mountains and coasts” that was first shaped in the field of literature has gone through visual and material magic in the field of contemporary art, and through the tangible qualities of the artworks, and even through a certain dynamic structure behind the art, the “mountains and coasts” as a signifier of aesthetics, has taken on a physical existence.

“What kind” of physical existence is this? If we look at the early mainstream art community’s references to Indigenous contemporary art from the 1990s and 2000s, we will often find critiques such as: raw, rough, primitive, wild…5 These are not unfamiliar terms. But what I want to uncover is the complexity of sexual desire behind the rhetoric.

One of the key features of the earlier development of Indigenous contemporary art was a tradition of labor that originated in craft, and those who returned to the tribal scene in the 1990s and structured a new cultural context through “art” or “cultural revitalization” include Rahic Talif, Yuma Taru, and Sakuliu Pavavaljung, basically all part of this kind of inheritance of crafts and labor. At that time, it was also this kind of inheritance relationship that carried a high degree of binary gender politics; gender temporarily returned to a binary imaginary, not only in the relationship between weaving culture and women, but also in the East Coast (which was actually the key time and space for the construction of the “mountains and coasts” aesthetics of the later art scene), through the creation of driftwood, which opened up the tradition of the close relationship between Indigenous contemporary art and the natural media, and so did Rahic Talif, who structured an art community from this.

Since then, the artistic lineage constructed of “driftwood” includes Iming Mavaliw, who first studied with Rahic Talif, as well as Amis who were active from the 2000s to 2010s: Siki Sufin, Sapud Kacaw, and Iyo Kacaw. Besides these Indigenous youths’ love for art and the land, most of these young Indigenous people have set down roots in their hometowns and embarked on a path of creation with a desire to return to their mother cultures, and to varying degrees they have entered the mechanisms and spiritual structures of their mother culture. As they become artists, they have also turned into “tribal men”. In the age class tradition of the Amis society, men at certain stages of their lives had to commit labor, work collectively, and bring up the younger ones, thus structuring a very special male community relationship. The driftwood-making communities going back to Rahic Talif seems to have continued this relationship structure, with men learning from their tribal brothers and each other in body through labor; this skillset and even the inherent relationship entails a single-gender lineage, an experience belonging to generations of men, a world exclusively of men.

This dynamic structure and process is, of course, inscribed in the language of the art work. Through collective labor and study, the artist reminisces about the abundance and ephemerality of the culture of the ethnic group or the mountains and the coasts. But on the other hand, it also carries a highly gendered quality. I can almost see flesh glistening in the sunlight, sweating between the towering giants that stand on the edge of the mountains and the coasts. In the 2000s, as these works, which are highly the result male labor processes and natural media, began to be pushed into the public view by the piercing eyes of the mainstream art community, the rhetoric that we had seen forty years ago, which is no longer unfamiliar to us, echoed inside and outside of the pillars of the black-and-white box. The artist’s love for Tieh Niu echoes in Crystal Boys, as he “finally found the primitive life on this island, just like the typhoon and tsunami on this island, which is a kind of awe-inspiring natural beauty”. The sexual fantasies of modern civilization towards pre-modern imagery have never disappeared from the field of knowledge production in art and literature, like Jenny’s love for Tarzan, sincere, colonial, and erotic.

Here, regarding the masculine qualities of the early indigenous “mountains and coasts” aesthetic tradition, we can see several major conditions for its development: the high proportion of males in the early stages of the production of literature and art, the gender and cultural structure of traditional ethnic groups, and the specific body of labor and inheritance relationships. To this day, the “mountain and coasts” symbol established in the 1990s still highly influences the mainstream development of Indigenous contemporary art. Through various exhibitions, discussions, and periodic art festivals that have become more and more expensive and larger in scale in recent years, this theory has become a marginal canon in the history of art in Taiwan.

As an observer of Indigenous contemporary art, I have never shifted my gender politics position since I wrote my first book. In the past, I have written about women and queer from the perspective of some kind of gender appendage, and I have not said a single word about men under the spectrum of “mountains and coasts aesthetics”. It’s not quite strange, yet it somehow is; but I’ve never hated these works. Back then, when I first went into the tribe and saw “these men” and their art, I began to understand Diderot, Picasso, Gauguin, and Modigliani (in different genders). I also understood SHIY De-Jinn and PAI Hsien-Yung. But for some reason, we find it difficult to process desire in such a context. In the 1990s, with the cultural revival of the post martial law period, the indigenous “mountains and coasts” tradition that had been established, its innate will to decolonialize, the resistance to power and objectification, it’s not only a highly masculine image, but also often stripped of (all kinds of) desirability. It is not pertinent to the question of desire. It is a question of gender.

Researchers pointed out early on in the discourse on Native American queers in North America that the gendered political structures of many decolonialization movements should be re-examined7. It is no surprise that Taiwan’s Indigenous contemporary art perpetuates the will and ethos of the post-martial law period, and that the masculine qualities of the early “mountains and coasts” imagery have a tendency to remove (various) narratives of desire. What puzzles me is that, if what I said above is not fallacious, today’s “mountain and coasts” symbols have long shifted from those of thirty years ago. To put it more bluntly, with the close and inter-exploitering relationship between Taiwanese Indigenous art and the wider national development strategy, and with this aesthetic symbol dominating and canonizing major local public sector exhibitions, art festivals, and the language of knowledge production, I wonder what had become of its original decolonializing core, its will to resist. If it’s already gone, alienated, I honestly don’t think it matters, it’s not something I care much about; but if it is, can this “mountains and coasts” aesthetics and its traditions, which were initially built around a specific gender-cultural structure, finally be placed into another, long-avoided context, including the intersections of sex and gender?

In fact, as early as in the early 2010s, in the field of literary development, researchers have already pointed out critically the gender problem in male-oriented literary writing from the standpoint of a female subject.8 However, when it comes to the contemporary art scene, the situation of art criticism is always “softer”, and I am not sure which end of the spectrum I am on, but I do not intend to be a binary hater of the history of the development of the art scene. Stepping outside the “male-female” perspective, this “mountains and coasts” alienated time and space is, to me, a more complicated angle of desire and a wrestling ground.

Through numerous writings, I have tried to fill the gaps in the life politics of different gender identities in the historical perspective of Indigenous communities, and I hope that Indigenous queers will no longer be hidden in the “maze” of traditional mountains and coasts aesthetics. Then, what about the queers in the mainstream who emerged from their specific population groups? When the Indigenous men and the queers, who have been repressed by different dominators, have reached the moment of emergence and even to the point of coming together, are the mountains and coasts still a maze, or is it ecstasy? If we flip through the “genealogy of desire” between modern civilization and pre-modern culture, or even between Han Chinese gays and Indigenous men which has been hidden in the development of our culture since last century, we may have a clear picture in our heads; as they return to their masculine “ecstasy”, we also embrace our dreams of desire. There is a popular saying that all gay men have a “hetero-masculine” fixation. In the face of these interracial/exotic/heterosexual men, what they cannot forget is intertwined in the post-colonial scene, they are able to criticize and also love, regardless of ethnicity, subjectivity, wills, and desires.

I fantasize that given the time, the queer and these men will give birth to the next generation of “mountains and coasts” children.