西元2019年12月,中國武漢爆發神祕冠狀病毒疫情。

西元2020年1月,亞洲各國開始封鎖;3月,歐、美、非、澳封鎖。

西元2021年3月,各國仍然處於封鎖狀態,部分國家封鎖程度更甚去年同期。店家不開、博物館與展覽空間關閉、宵禁、出門須申請許可、除國民與居留者外不得入境,而航空交通也僅恢復至尚稱通行的狀態。

雖說各國疫情百百種,從嚴格軍事管制的中國、嚴密追蹤傳播路徑並且封閉邊境的臺灣,到凡事看機率、努力降低接觸的歐洲,抑或是將經濟活動擺在第一優先的墨西哥,人類在這些區域的活動與心理狀態都受到了一定程度的影響。

冠狀病毒以類生命體的物質存在,從第一位患者身上開始大量複製、散播,進入第二、第三、第一千、第一萬、第一億個人,並從康復的人身上消聲匿跡,或是與不幸器官衰竭離世的人一同死去,COVID-19冠狀病毒的故事也是人類的故事,是與人類共同書寫的生物歷史。病毒如常,而改變的或許是人。

疫情早期,在歐美為了疫情處理方式爭論不休、民間拒絕封鎖的時候,由矽谷的西班牙裔工程師湯馬斯.普尤(Tomas PUEYO)在Medium平台上發表〈冠狀病毒:鐵鎚與舞〉(Coronavirus: The Hammer and the Dance)1,相關文章獲得四千萬瀏覽量。他認為防疫的封鎖,就如同人類與疫情的共同之舞,在疫情高漲的時候使用極端封鎖手法,並在疫情降溫時與疫情共同相存,如同共舞。不意外的,在各種科學證明、道德勸說、政府措施,似乎「舞蹈」這一個文化性的詞彙得到了最跨國界的迴響。許多人試圖透過這篇文章所使用的譬喻來說服身邊反對積極防疫措施的人們。

在經歷了一整年的動盪與改變後,不難理解「鐵鎚與共舞」防疫法這一譬喻的精妙之處。因為病毒的快速複製,與密切透過人類互相接觸的途徑散播,防疫的措施成為一連串精密的機率計算,而體現在政府策略上就成為每週更新的「禁止執行項目」:這週關閉所有餐廳、下週開放外帶;這週商店照常開放,記者會隔天所有商店關門,三週後開始提供預約取貨;這週博物館關閉,記者會隔天開放預約參觀,再下一週的記者會決定隔天再度全面關閉;這週歐盟居留簽與文化簽證可以正常入境,記者會隔天宣布短期居留簽與文化簽證不可入境。朝令夕改的策略,其實是政府試圖維持經濟活動與壓低疫情的方式,但給所有人丟下了巨大的難題。對於大量仰賴實體經驗的生物藝術領域,更是影響巨大。觀看過去這一年中領域內相關的大型藝術節、小型展覽、社群活動,不禁要驚豔於因為「病毒」這一個生物存在激發的各種嶄新人類經驗。

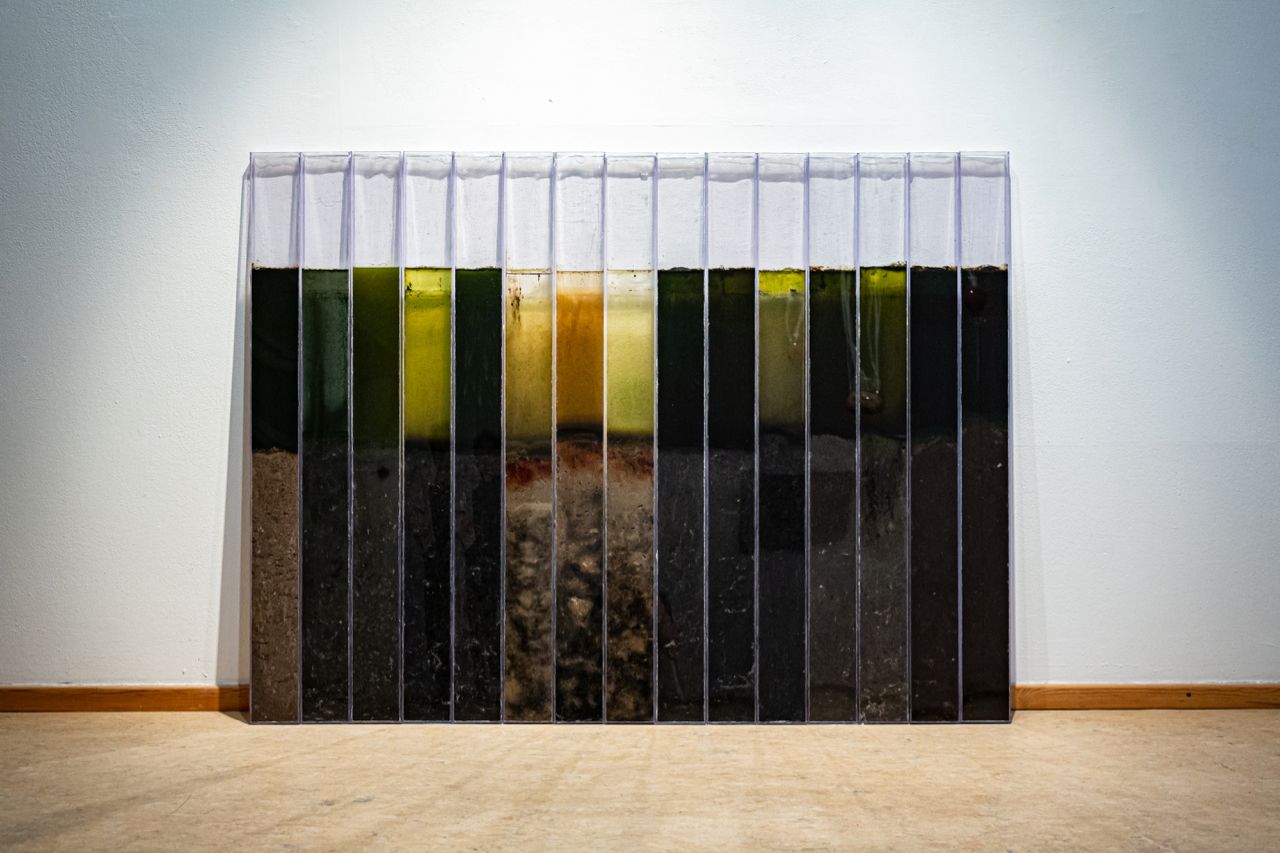

Nicole CLOUSTON的作品《柏林泥土》(Mud Berlin,2020)於展覽「卡米爾日記」(THE CAMILLE DIARIES)中的展出現場。圖/Tim DEUSSEN攝影, Art Laboratory Berlin提供

Nicole CLOUSTON的作品《柏林泥土》(Mud Berlin,2020)於展覽「卡米爾日記」(THE CAMILLE DIARIES)中的展出現場。圖/Tim DEUSSEN攝影, Art Laboratory Berlin提供

Nicole CLOUSTON的作品《柏林泥土》(Mud Berlin,2020)局部 。圖/Tim DEUSSEN攝影, Art Laboratory Berlin提供

Nicole CLOUSTON的作品《柏林泥土》(Mud Berlin,2020)局部 。圖/Tim DEUSSEN攝影, Art Laboratory Berlin提供

隔離與斷航,防疫措施所阻斷藝術界所熟悉的「實體所在」,卻也打開了新的實體經驗。柏林的藝術單位「柏林藝術實驗室」(Art Laboratory Berlin)經營主軸為科學與藝術,並試圖透過展覽與論壇、工作坊、藝術駐村以及各種形式的策展人與藝術家對話,建構長期的合作關係,同時因為兩位策展人的背景為藝術理論與藝術史,該機構也進行許多學術寫作研究。柏林藝術實驗室去年共進行了兩場展覽,兩場展覽皆展出使用活體微生物為素材的作品,並在展覽期間持續生長。第一場為疫情前開幕的「細菌無國界/殖民主義現金」(Borderless Bacteria/ Colonialist Cash)展覽,參與該展的美國藝術家Ken RINALDO在開展之前就表示為了減少碳足跡,他希望提供柏林藝術實驗室策展人Christian DE LUTZ與 Regine RAPP標準的操作程序,委託兩位策展人在柏林直接委託製作。而第二檔展覽「卡米爾日記:關於母性/他者、生命及關懷的藝術新視野」(THE CAMILLE DIARIES: New Artistic Positions on M/otherhood, Life and Care,簡稱「卡米爾日記」)適逢疫情封鎖與國際斷航,某幾件作品原本計劃以常見的藝術家現地製作方式進行,最後決定同樣委託兩位策展人與策展團隊製作,而展後的作品拆卸也交由策展人執行。使用微生物活體的展覽,其中一個關鍵為展覽過程中「作品」是持續生長的。策展人Christian DE LUTZ與 Regine RAPP表示,他們作為策展人已經習慣了藝術家作為作品裝置執行者,而策展人總是與作品的裝置過程保持一段距離,因為疫情封鎖,使得他們必須參與藝術家的製作過程,而看到了藝術實踐的新面向。「卡米爾日記」展覽中,藝術家Nicole CLOUSTON的作品使用19世紀微生物學家謝爾蓋.維諾格拉茨基(Sergei WINOGRADSKY)所發展的微生物管柱(Winogradsky Column)技術,採集柏林不同地點的泥巴,再放置於封閉的微生物管柱中並加入讓微生物生長的養分,隨著微生物的增長讓管柱出現豐富的色彩與大理石般的花紋,成為作品《柏林泥土》(Mud Berlin)。原本的執行計畫為兩位策展人協助接洽當地的微生物學家,在藝術家到達柏林時協助製作。新的執行方式則變成藝術家提供執行步驟,由策展人與當地團隊合作執行。Christian DE LUTZ與 Regine RAPP認為這個過程讓藝術實踐變成團隊式的、眾人式的合作,並且需要更多策展人與藝術家之間的信任。而胥貝拉.佩區克(Špela PETRIČ)的作品《植物畸形學》(Phytoteratology)也因為當地專業生物實驗室封鎖而無法借用,只能使用容易產生樣本污染的自製實驗室,而需要進一步討論「污染」在作品執行與概念中的意涵。策展人與藝術家之間對於作品有不同於疫情前「作品必須盡量原封不動展出」這樣的優先順序,而開啟了原本不會有的深刻討論,並且雙方欣然接受對話後的成果。

胥貝拉.佩區克(Špela PETRIČ)的作品《植物畸形學》(Phytoteratology,2020)於展覽「卡米爾日記」(THE CAMILLE DIARIES)中的展出現場。圖/Tim DEUSSEN攝影, Art Laboratory Berlin提供

胥貝拉.佩區克(Špela PETRIČ)的作品《植物畸形學》(Phytoteratology,2020)於展覽「卡米爾日記」(THE CAMILLE DIARIES)中的展出現場。圖/Tim DEUSSEN攝影, Art Laboratory Berlin提供

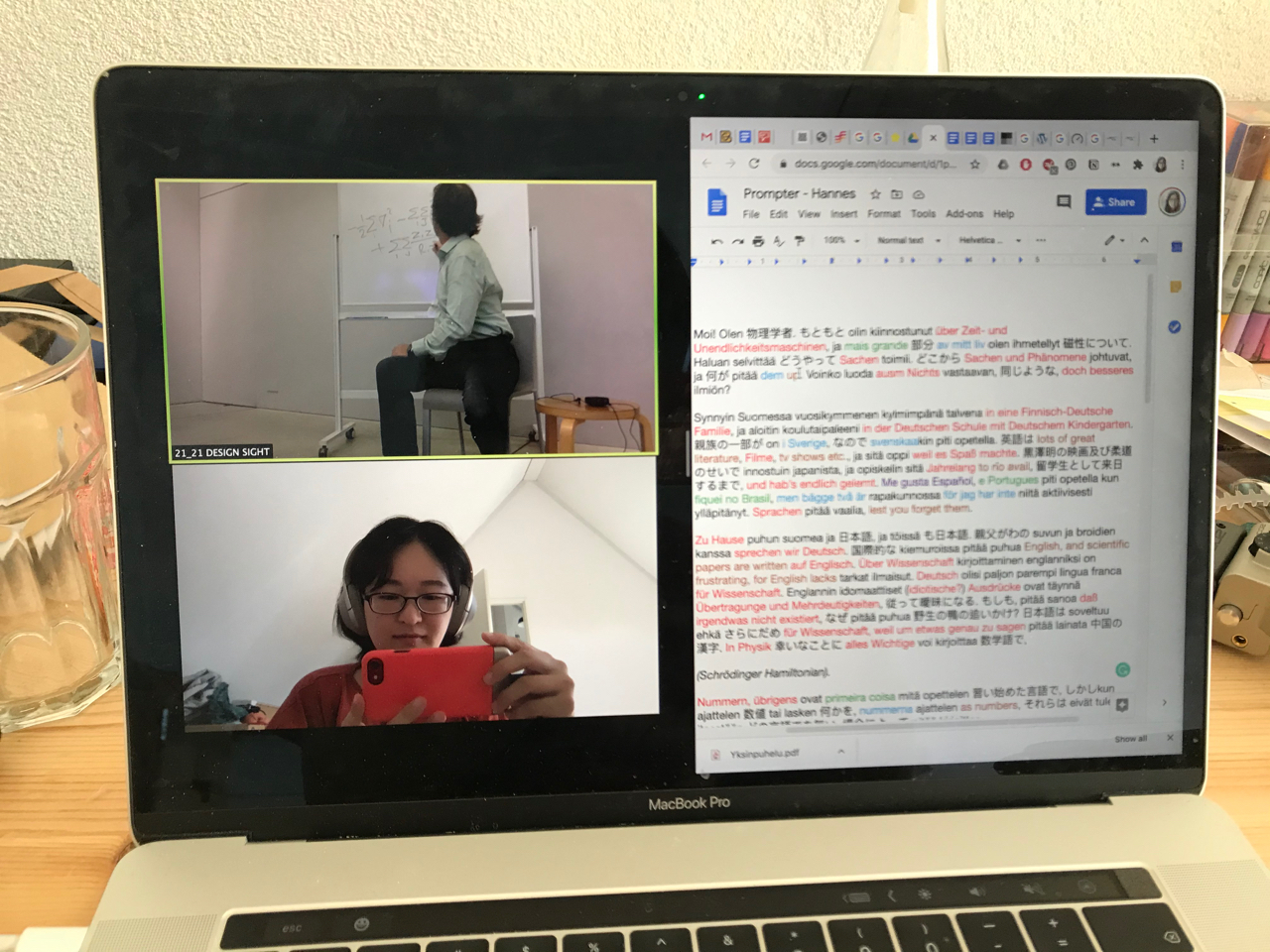

同樣的由於斷航、封鎖所導致的策展人與藝術家合作作品轉換再製,也同時發生在筆者身上。筆者受Art & Science Node所邀,原訂於2020年3月在阿姆斯特丹舉辦的World Bio Market活動中展出,卻因疫情延至2020年11月、又延至2021年3月,最後主辦方World Bio Market公司宣佈解散清盤。Art & Science Node轉而與Plant Biology Europe高峰會合作,並考慮在「就算室內空間無法進入也還是可以進行的展覽方案」,發展網路VR平台,將作品轉換至VR空間中。不同於將作品直接轉移至AR空間中成為數位藝廊,Art & Science Node團隊與藝術家個別討論,並思考作品在AR空間中的新表現形態。例如筆者作品《病毒之愛》中印有約七千個病毒名稱的捲軸,轉換成AR空間中以雲狀方式呈現出所有病毒名稱,當觀者帶著手機走過空間中,便會有許多病毒名稱漂浮通過觀者身邊。在這件作品中,參與者將體驗一場病毒餐宴,吃下數道加入病毒的餐點及飲品,本作受邀臺灣當代文化實驗場 (C-LAB)之邀,於2020年6月為展覽「虛幻生命:混種、轉殖與創生」製作線上外送版本,並由展覽製作人陳品伊負責招募作品參與者、協調空間與外送機制的安排及拍攝轉播,筆者則與廚師吳柏毅遠端試菜。同樣地,筆者受邀參與東京21_21設計美術館的「翻譯:理解你的不明白」(traNslatioNs – Understanding Misunderstanding)展覽委託,為該展覽再製了五個人造個人語言的錄像,參與者包含該展的策展人Dominique CHEN與另外四位旅居東京的多重語言背景居民。執行方式為由日本方準備空間、攝影團隊,而藝術家負責線上前置訪談與獨白練習,在預約好的日子將所有參與者邀請至21_21設計美術館的空間中拍攝。拍攝同時,筆者透過Skype與電腦,在旁邊同時監測與討論,並由當地製作團隊用手機拍攝相機畫面。在這過程中藝術家的身分其實只能掌控50%的事情發生,而剩下的50%皆需要仰賴在地團隊的能力。

柏林藝術實驗室策展人Regine RAPP提到,「卡米爾日記」展覽還配合有一個十小時的線上論壇,不僅吸引到上千人觀看,大多數人不住在柏林,拓展了原本的觀眾群,對於策展人的個人經驗來說,藝術家的「存在感」其實不輸實體出席。在實體空間中的作品、動手參與的製作過程帶來從未有的感官經驗,配合上藝術家的對談,彷彿藝術家就在身邊。而與觀眾的關係也有更加深入的轉變,因為必須一對一預約參觀,策展人能與每一位觀眾深入討論作品,開啟新的對話空間與觀展模式。

「存在感」透過網路所建構出的真實性,同樣發生在筆者自身的經驗中。貨物的國際旅行遠較於人類的國際旅行容易,但生物藝術作品中的「生物」卻無法旅行,必須透過網路在當地尋找替代品,這「實體產出」(physical production)的需求而讓策展人、製作人、執行團隊與參與者產生可分享的、進行中的製作體驗,產生除了「觀看」以外理解作品的方式。而持續改變的疫情狀態,讓多方需要隨時確認對方所在地因應疫情而改變的實質調整,例如「是否可以多人在同一空間中」、而遠端對於對方的環境與空間有更深入的理解。

疫情所迫使的數位化,在時間的實踐上也帶來全新氣象,瞬間將藝術領域推進虛擬空間。虛擬空間的使用,在藝術領域中一直少被探索,就連新媒體藝術領域的龍頭老大林茲電子藝術節(Ars Electronica)也是全新的嘗試。林茲電子藝術節在2020年5月時決定改為線上展覽與實體展覽並行,並透過原本就有的合作網絡,將展覽去中心化、提出「克卜勒花園」(Kepler’s Gardens)的概念,讓展覽分散到數個國家共120個各地點展出,並在同一天開展。展期間也同時進行線上四個頻道24小時不打烊的五天密集論壇。除了論壇轉播,林茲電子藝術節也實驗了Hubs by Mozilla提供參與者不期而遇的聚會空間。Hubs by Mozilla是開放免費的VR空間,使用者登入後可選擇自己的電腦化身(Avatar)圖示,該化身會連接到使用者的麥克風,讓使用者在空間中透過麥克風與旁邊的角色(另一位使用者)對話。這個改變也讓林茲電子藝術節的工作團隊有巨大的變化。過去林茲電子藝術節讓展覽分佈於林茲這座城市中,需要大量的佈展與顧展執行人力、專案經理、行政等,大約200人;今年的人事分配改將大量人力分配在管理網路系統、轉撥、記錄的技術支援與執行,佔整個團隊的一半人數,並且團隊縮減至60人。

因時區而擴張的活動時程,也出現在柏林藝術實驗室的展覽「卡米爾日記」衍伸線上論壇2。論壇根據講者的時區安排演講順序,從日本與澳洲開啟第一場論壇,終止於美洲,為時十個小時。透過YouTube轉播,讓參與者可以在YouTube上即時提問,並且在活動結束後直接有線上的錄影可以重播。此模式也同樣被林茲電子藝術節使用,因為線上化而有前所未見的詳細活動紀錄。

林茲電子藝術節在傳統展覽的內容之外,改變內容策略,將部分原本使用在藝術家的旅費與住宿費、實體展出的材料費,轉換成新的影片委託製作,由原本欲邀請的藝術家提案,並給予製作經費,在藝術節的五天中線上直播。同時,林茲電子藝術大獎(Prix Ars Electronica)與STARTS Prize的評審工作,傳統上邀請世界各地評審飛到奧地利進行,2020年也改由線上舉行。透過網路工具Miro此一線上視覺白板工具作為評審討論的平台,讓世界各地的評審在作品之下加上註解與評語,也恰好能同時記錄下評審過程的動態。

林沛瑩與21_21設計美術館以遠距工作完成展出作品的討論過程。圖/林沛瑩提供

林沛瑩與21_21設計美術館以遠距工作完成展出作品的討論過程。圖/林沛瑩提供

林沛瑩與21_21設計美術館以遠距工作完成展出作品的討論過程。圖/西田麻海江提供

林沛瑩與21_21設計美術館以遠距工作完成展出作品的討論過程。圖/西田麻海江提供

2020年是國際航空的寒冬,卻是網路的盛世,困在家中的人們開始透過各種網路工具相互連結,並嘗試塑造共同的實體經驗。2020年3月,美國策展人Claire NETTLETON開始了以「病毒文化」(Viral Culture)為主題的每週六線上聚會,參與者以北美社群為中心逐漸拓展到歐洲社群、總共約200人,進行了九場以上的討論。日本東京的BioClub Tokyo與德國的柏林藝術實驗室從2020年4月至2021年3月,定期進行了十場次的「病毒雲」(Viral Cloud)聚會,邀請日本與歐洲的混種藝術家3與生物自造圈參與。以波蘭為主要據點、由Joanna HOFFMAN博士主持的Art & Science Node在波蘭時區的每週二晚上10點有「藝術科學」(Art Science Meeting)聚會。每週間歐洲下午則有「藝術、科學與科技中的女性」(FEMeeting,Women in Art, Science, Technology)籌辦的「午茶雜談」(Teapot Chat),以藝術家Marta DE MENEZES與Dalila HONORATO作為主要策動者。週一則有美國學者Eben KIRKSEY的「冠狀病毒多物種讀書會」(Coronavirus Multispecies Reading Group)。頻繁的跨國連線聚會,替代了原本以各個展覽開幕聚會為核心的國際藝術社群連結,產生新的合作機會與學術對話。

唐娜. 哈洛威(Donna HARAWAY)2016年的著作《與困擾為伍》 (Staying with Trouble)。圖©Duke University Press

唐娜. 哈洛威(Donna HARAWAY)2016年的著作《與困擾為伍》 (Staying with Trouble)。圖©Duke University Press

科學藝術、生物藝術、混種藝術(hybrid art)社群在這次疫情中獨特之處,莫過於成員們在疫情前便有擁有深入理解微生物與社會、文化脈絡的藝術方法論,或是藝術實踐。對於「微生物與人」的關係,始終是社群中的主要關注點,生物科技的最新發展也是社群中的基本知識。當疫情來襲,第一波的討論是「人類對微生物的理解總算往友善的方向前進,是否會因為這次的疫情而重新喚起對微生物的恐懼」、「多年來總算說服展覽空間接受微生物展出,是否會被禁止?」、「疫情讓人們以及使用微生物的藝術實踐者重新深刻理解到人類也是自然界的一部分,也許將人/自然的假設有根本的錯誤」、「微生物的不可見、難以預測所造成的焦慮,是否藝術能提供出口?」。COVID-19成為一次海嘯般無法避免的「與他者接觸」(encountering others)契機;唐娜. 哈洛威(Donna HARAWAY)的著作《與困擾為伍》 (Staying with Trouble),頻繁地被提出討論:「是否持續的封鎖與放鬆、維持社交距離,正是一種與病毒『締親』(making kin)的方式」。疫情前期的混種藝術家們發起了巨大的責任感與對自我藝術實踐的深刻反思,同時開始尋找藝術實踐在疫情中的實用性,而疫情似乎也實證了混種藝術家們對於微生物與人類共存的探索有其迫切性(urgency)。柏林藝術實驗室就提到,柏林的參議院因為疫情,主動邀請柏林藝術實驗室提案,因為「這就是科學藝術、生物藝術、混種藝術的專業」。

當COVID-19疫情在各國都來到第二波、第三波的2020下半年,對話又再度轉變,病毒所間接導致的身體禁錮、阻隔疫情傳播的社交距離,與因應疫情發展出的各種無接觸服務(例如自動開門、卡片無接觸付款、手機掃描付款),讓社群重新關注因人類與病毒親密接觸所帶來的觸覺疏離感,重新思考身體的邊界定義、內在與外在的分別。同時,病毒在人類群體中散播、與人類政府組織、防疫政策互動後,也產生了特定的「速度感」。Art & Science Node主要經營者Joanna HOFFMAN與Karolina WLAZŁO-MALINOWSKA就表示,在這疫情的第一年中,根據疫情前所建構的執行結構,因為無法快速適應疫情的狀況,持續延期,導致許多展會的破產。也因此,Joanna HOFFMAN認為面對病毒所帶來的挑戰,必須快速正面迎擊並且尋找替代方案與新方案,工作方式也因為無法見面,需要發展新的合作模式。Karolina WLAZŁO-MALINOWSKA則認為現在必須考慮到人類不見得能追得上病毒變化的速度,執行的風險性遠較以前更高,實際的環境狀況可能與預期中的不同,虛擬網絡的活動也逐漸因為過多的線上聚會與極度欠缺的實體聚會,線上活動開始顯示出疲態。同時,他們認為全球封鎖的這一當代大型人類行為實驗,也證明了人類有能力可以將某些大型系統與行為暫時暫停,來面對看似無法施力的議題如氣候變遷。

因為虛擬化所喪失的觸覺經驗,究竟是喜或憂?Art & Science Node的「Rhizosphere計畫」,原本規劃定期實體聚會能直接接觸微生物,透過實體經驗去拓展討論,也因為社交距離與封鎖,必須線上進行,而他們認為實體經驗是無法被取代的。但同時,線上的聚會,卻可以較低的門檻參與,所以是個讓聚會進入適當節奏的方式;因為疫情被迫使用的通訊軟體也增加人與人之間的小互動。而諸如Art & Science Node、挪威生物藝術場(NOBA – Norwegian Bioart Arena)、荷蘭V2_、丹麥Recoil Performance Group都在過去這一年中進行了將部分工作坊材料寄至參與者家中,半實體、半線上的工作坊。

若要談新型冠狀病毒此一生命與非生命之間的生物體,究竟在過去一年多中與人類共同譜出了什麼舞,大概莫過於是前所未見的豐沛生命力之舞。正如柏林藝術實驗室策展人Regine RAPP說的,因為疫情,我們被迫持續的重新協商,也是一個全球的共同挑戰。這個持續的重新協商,也讓原本平凡的日子充滿了實驗性,進而激發出了各式各樣新的可能性。而這,就是目前人類與病毒的共同之舞。