當嚴重特殊傳染性肺炎(COVID-19,武漢肺炎)自2月中旬開始在歐洲擴散,包括義大利、西班牙、英國等疫情較為慘重的國家開始實行大規模的封城、隔離、關閉學校與公共設施、限制社交活動等緊急措施。與此同時,包括喬治.阿岡本(Giorgio Agamben)、讓-呂克.南希(Jean-Luc Nancy)、羅伯托.艾斯波西多(Roberto Esposito)、斯拉沃熱.紀傑克(Slavoj Žižek)、大衛.哈維(David Harvey)等全球知名哲學家莫不對疫情與防疫措施發表評論,引發熱絡的論戰。若說在過去這幾個多月的時間裡COVID-19的全球性擴散連帶引發病毒論述的過度生產,似乎並不為過。姑且不論各自立論點的差異,這波論戰主要聚焦――如果有的話――在政府的防疫措施如何限制甚至侵犯人權和引發集體恐慌、民粹主義與恐外症伺機竄起。本文主要的目的在於釐清這波論戰的一些關鍵,進而反思當前的生命政治情境。

當代義大利最重要的哲學家阿岡本於武漢肺炎疫情開始在歐陸(特別是義大利)擴散之際,就在2月26日義大利文刊物《Quodlibet》發表評論,隨即被翻譯成英文〈The Invention of an Epidemic〉迅速在網路媒體流通,引發廣泛討論。1阿岡本引述義大利官方機構的資料指出,只有10-15%的感染個案會有嚴重的症狀,絕大部分都屬於輕症。阿岡本對於客觀事實以及義大利和整個歐洲後來的疫情發展的掌握是否精準,也許值得再商榷。大體上阿岡本認為整個義大利社會對於疫情過度反應。政府部門的運作已無異於軍隊,為了對抗病毒傳染,以衛生和安全為由採取的緊急措施坐實了「例外狀態常態化」的治理模式,包括封城和關閉學校和公共設施的緊急措施成為日常生活情境,嚴重侵犯人民的自由。這樣的觀點事實上貫穿了阿岡本長期以來的著作,如同他認為集中營就是現代政治普遍的治理模式,民主與極權體制之間存在著秘密的連結。阿岡本同時也認為這樣的緊急措施和社會大眾的集體恐慌形成一種惡性循環,彼此相互強化。可惜的是,阿岡本並沒有舉證政府如何挑動人民的集體恐慌,藉此證成緊急措施的正當性。

阿岡本發文的隔天,法國哲學家南希立即以〈病毒的例外狀態〉(Eccezione virale)一文作為回應。南希反對阿岡本將新冠病毒傳染「常態化」,視之與一般流行性感冒相同。南希顯然比阿岡本更能掌握醫學上的客觀事實,畢竟武漢肺炎現在尚未有可靠的疫苗,而且它的症狀多變,對身體各器官功能可能會有不可逆的後果,不同於流行性感冒。南希強調傳染病和防疫的問題涉及生物、科學、文化等面向,不能像阿岡本那樣把問題簡化成政府措施。不過南希並沒有進一步具體分析那些複雜交錯的面向。但是我們可以確定的是,我們不應該忽視個別情境,將任何單一的理論模式套用到有關病毒和防疫措施的討論,不論是米歇爾.傅柯(Michel Foucault)談的隔離措施或阿岡本的「例外狀態常態化」。

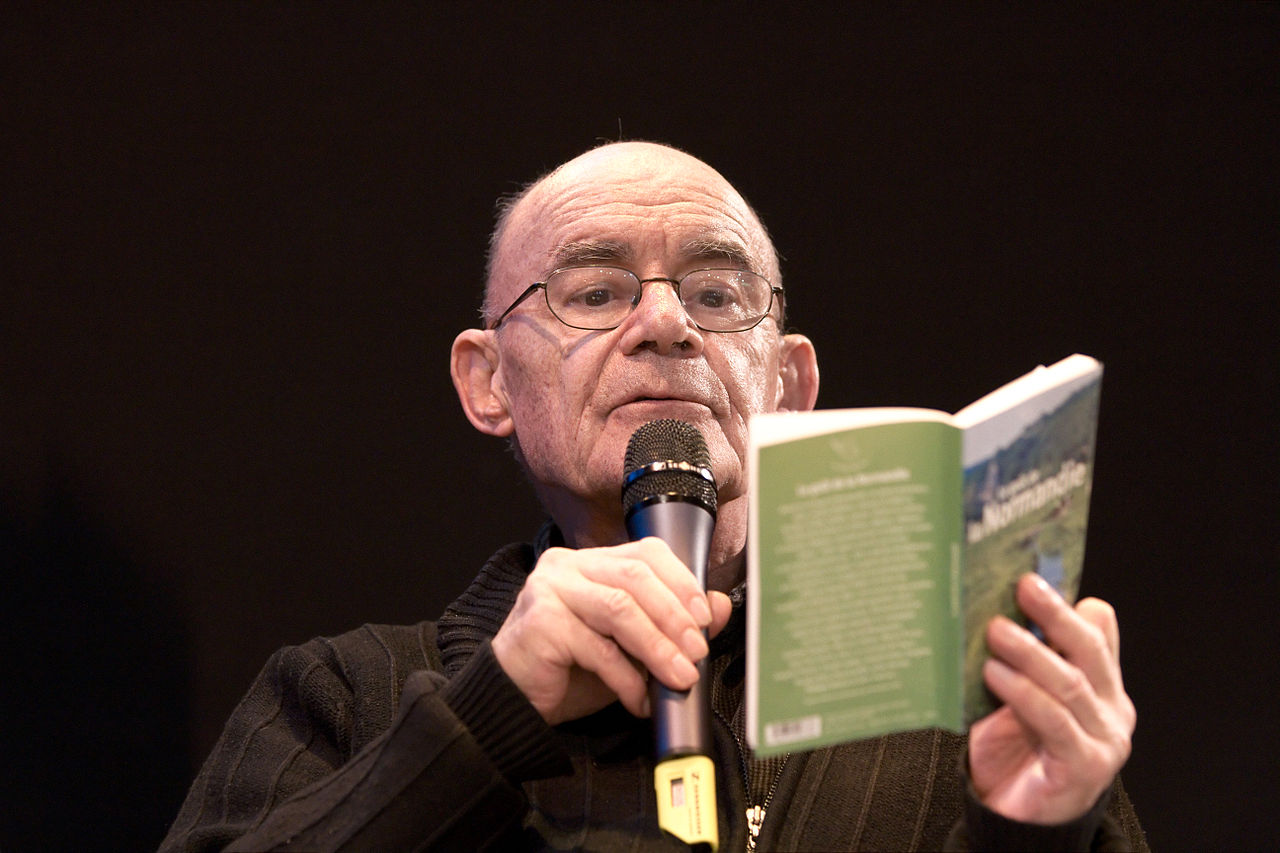

讓-呂克.南希(Jean-Luc Nancy)以〈病毒的例外狀態〉(Eccezione virale)一文回應喬治.阿岡本(Giorgio Agamben)對於COVID-19的觀點,也掀起了哲學家們的論戰。圖/Georges Seguin (Okki)、CC BY-SA 3.0

讓-呂克.南希(Jean-Luc Nancy)以〈病毒的例外狀態〉(Eccezione virale)一文回應喬治.阿岡本(Giorgio Agamben)對於COVID-19的觀點,也掀起了哲學家們的論戰。圖/Georges Seguin (Okki)、CC BY-SA 3.0

緊接著是另一位義大利哲學家艾斯波西多加入論戰。艾斯波西多認為南希拒絕涉入生命政治是不智的做法,顯示他對生命政治全然負面的理解是一種誤讀。對艾斯波西多而言,生命政治已是無所不在、無法回避的事實。生物和基因工程介入傳統上被認定是自然過程的生育與死亡、生化恐怖主義、移民管制、乃至傳染病,再再都是生命政治的課題。即便如此,艾斯波西多還是提醒我們必須具有歷史意識,必須關照不同歷史階段的生命政治模式的特殊性,也必須區分近期的事件和長期的過程。醫學的政治化也許是通則,但是當前防疫措施如何透過醫療行為進行社會控制,恐怕還是得有更確切的個案論證。艾斯波西多在文章最後指出,義大利的疫情反映的比較是公共性權威的崩壞,而不是極權主義戲劇性的緊縮。這樣的釐清無疑也是提醒我們不應該過大誇大阿岡本「例外狀態常態化」和「民主和極權體制的秘密連結」。我們是否也該區分類似集中營裡的那種永恆的例外狀態――也就是再難以想像的違反人性的罪行每分每秒都可能發生――和暫時性的、策略性的、而且是可協商的例外狀態?

延續前文最後的提問,哲學家們關於肺炎疫情的論戰,在多大的程度上深化或改變我們對於當前生命政治情境的理解,乃至於反饋、修正或重塑生命政治理論概念和框架?印度學者杜薇維蒂(Divya Dwivedi)與蒙罕(Shaj Mohan)從宏觀的歷史複雜化對於「例外(狀態)」的理解,將人類視為「技術例外的製造者」。從他們的觀點來說,包括疫苗注射等人類對於生態系統或自然時間性的介入(interventions)都是例外狀態,而當代生命政治論述經常忽略人類與其他物種或生命形式的連結。正當世界各國因為武漢肺炎疫情擴散而進入封城和限制觀光旅遊的「例外狀態」,也就是說,當人類為了自我防護避免病毒感染而減少移動與生產活動,無意中數十萬隻海龜游上印度海岸產卵,北極的臭氧層也出現修復現象,這是否可稱之為「例外狀態的例外」?這當中的確切因果連結也許有待更深入的科學論證。在防疫期間大量使用的口罩、防護衣、酒精、次氯酸水或其他消毒用的化學產品,又會對其他物種生命和生態環境造成什麼衝擊?以自我防護為目標的生命政治措施該如何能回應其他物種生命與非人的物質環境存在的要求?或者是否該思考一種「沒有人類的生態生命政治」?更根本地問,我們的思考是否被某種僵化的生命政治框架所綁架?

如同英國華威大學(University of Warwick)學者丹尼爾.羅倫奇尼(Daniele Lorenzini)在〈新冠病毒時代的生命政治〉(Biopolitics in the Time of Coronavirus)一開始指出的,肺炎疫情的擴散帶來了和病毒傳染病和隔離相關爆量的論述,於是傅柯(又)成為爭相引述的對象,當中有許多誤讀和誤用。羅倫奇尼釐清,傅柯談的生命政治並沒有惡的本質,是一種以生物性生命為重心的治理理性,標示著現代性的門檻,區隔現代與傳統權力和社會運作模式。羅倫奇尼強調,要拒絕被(作為一種理論框架的)「生命政治」綁架,就必須避免落入捍衛或反對生命政治的兩極化選擇。生命政治作為一種治理模式不僅在例外狀態也在常態之中運作。我們不僅關注包括隔離的種種防疫措施如何侵犯人權,也不能無視更為隱形、自動化的常態性權力運作。除此之外,羅倫奇尼也從傅柯的角度強調生物權力(biopower)和種族主義的連結。這樣的連結不論在常態或例外狀態,都顯示生命政治的治理下,生物的連續體被斷開成不同種族群體的等級,不同的種族接受不平等的醫療照護,也因此暴露在不同程度的風險。這也就是羅倫奇尼所說的「差異化的脆弱性」(differential vulnerability)。差異化的脆弱性涵蓋的層面似乎不限於種族,大眾運輸司機、送貨員、藥師等日常生活情境中的群體都暴露在較高度的風險之中,他們是不是也可以被界定為「防疫照護工作者」甚至是「防疫英雄」,醫療權利更應該受到重視?羅倫奇尼最後提醒避免落入「危機的話術」因而尋求立即性的對策,反而不願意真的改變既有的生活、生產、旅行等的方式。

為了防止COVID-19擴散,義大利的封鎖政策持續實施,照片拍攝於2020年4月22日,威尼斯一間商店的老闆於未開門的店舖中。圖/達志影像、REUTERS

為了防止COVID-19擴散,義大利的封鎖政策持續實施,照片拍攝於2020年4月22日,威尼斯一間商店的老闆於未開門的店舖中。圖/達志影像、REUTERS

在包括封城、限制旅遊與社交活動等「例外狀態」防疫措施的前提之下和之外,我們還可能談什麼「自我治術」(technologies of the self),開展出「例外狀態的例外」?當代法國哲學家凱瑟琳.馬拉布(Catherine Malabou)在她的〈隔離隔離:盧梭、魯賓遜和「我」〉(To Quarantine from Quarantine: Rousseau, Robinson Crusoe, and ‘I’)中,先從盧梭在他的《懺悔錄》記載的一個軼聞談起。盧梭在1743年從巴黎到威尼斯旅行,當時義大利西西里島上的墨西拿傳出瘟疫,奪走近5萬人的性命。盧梭根據緊急命令必須接受隔離21天,但隔離的處所完全沒有任何日常生活器具。盧梭就地取材和善用他隨身攜帶的材料,拼湊出坐包括墊、被單等必需品。盧梭自詡為魯賓遜,兩人都在與外界隔絕的生活中進行即興創作。

馬拉布從盧梭的軼聞導引出人生選擇的思考。在一個隔離的時代中什麼是最好的選擇?和所有人一起被隔離,或者自己一個人被隔離?馬拉布似乎認為比較好的個人選擇是能夠隔離於隔離措施,也就是既在隔離措施中又與之保持距離,從集體的隔離狀態中創造出一個類似盧梭/魯賓遜的孤島。「隔離隔離」意謂著在傳染病擴散的艱困時刻中,保有自發性和創造性的生活,距離因此是自我培力的必要條件。馬拉布最後將思考導向「遠距的社會性」(the social in the distance),她並不認為防疫措施下的隔離和社交活動限制強大到足以摧毀這種社會性,那是一種同時能夠自處並且與他人共在的另類選擇。對她而言,「孤獨」(solitude)有別於「疏離」(estrangement),孤獨是寫作和其他創造性活動不可或缺的條件,也是自我照料和自我治術的一環。

馬拉布對於防疫措施的反思具有相當程度的倫理普遍性。然而,「隔離隔離」和作為一種自我治術的孤獨和距離如何成之為一種有意義的選擇,特別是和作為防疫措施或生命政治管理一環的「自主管理」有所區隔,還值得更進一步思考。我們如果深入理解當前生命政治的普遍情境,我們也許會發現兩者的區隔並非顯而易見。阿岡本的「裸命」或以集中營作為範式不足以完全涵蓋(但並非完全不適用)當前生命政治與其說是弱化或剝奪生命或任其死亡,不如說是控制、管理和強化生命的各種能力(Rose 3),特別是面對各種形式的傳染病風險。

從歷史脈絡來說,自17世紀早期現代時期以來,健康衛生已然成為國家治理的核心,緊扣著政體的生產能量和戰鬥力。不論是霍布斯、盧梭或孟德斯鳩等共和主義政治哲學家也大多強調,共和政體有責任保護人民免受病原感染。生命政治的免疫力防護一直以來都是要維護地理、生態、物種和物質的界線,但病毒或任何傳染型的微生物讓界線顯得危脆(precarious)。特別在當前的全球化情境中,病毒的擴散和演化路徑越形複雜、越不可測,病原與宿主偶發性的連結讓傳染病不斷衍生出新的症狀。不只像此次的武漢肺炎極有可能會衍生出日常的慢性病,各種癌症、腫瘤、免疫系統失調、身心症等,也都變得更不確定、更難以救治與痊癒:這是一個無法談末期或終端的時代,我們的病或症狀永遠都好不了,我們已經進入一個新的慢性病模式,「治癒」的邏輯已經被「管理」或「控制」取代 。

事實上,當前生命政治情境中的危脆性並不僅限於疾病,從投資理財、交通、食品、老化、工作,到環境污染、恐怖主義攻擊、各種形式的暴力,莫不顯示不穩定、脆弱與危急的本體存在。然而,如同食利資本主義(Rentier Capitalism)以債養債,兼職、約聘等非典型勞動在各行各業都日趨普遍化,顯然危脆性已成為新自由主義治理邏輯的一環。從這個角度來看,我們如何確定「自我治術」或「自主管理」是不是新自由主義生命政治的一環,或者如何抵抗那樣的治理邏輯?主體隸屬和培力的界線如何劃分?脆弱的生命如何值得活或無法忍受?

對於這些如此巨大的問題,我無法也不願提出立即性的解答。正當臺灣人因為防疫成效得到舉世肯定,民族驕傲感創歷史新高的同時,各種限制也在逐步解除當中,盡快從例外狀態回歸常態儼然是全民共同的願望。這是否是把問題誤視/識為解答?是否是對於整個治理、甚至從剝削和壓迫結構的偏盲?

我姑且用一個精神分析界流傳已久的笑話結束這篇短文。一位病人掛號看診,精神分析師先問助理病人的狀況是否緊急。助理回答,「不,病人看起來還算穩定,運作的還可以,還能適應現實狀況,不算緊急。」分析師大叫,「那不行,我最好趕快看看他!」