受空總臺灣當代文化實驗場(C-LAB)的邀請,生物藝術創作者宮保睿與顧廣毅進行一項「C-LAB生物藝術實驗室研究案」,針對國內外三十多個生物藝術相關的實驗室進行整理與研究,作為日後C-LAB建置生物藝術實驗室的參考依據。本文摘錄部分研究內容,並分成四個部分,前兩段由顧廣毅執筆,後兩段則是由宮保睿負責。第一段從生物藝術家於自己工作室自製生物駭客(Biohacking)實驗室談起,到第二段介紹文化機構建置生物藝術實驗室的例子,第三段拓展到大學中專業生物科學實驗室中的生物藝術實踐,最後第四段則是延伸到思想層次的生物藝術實驗室觀察。希望透過這篇文章,梳理生物藝術實驗室研究案的核心內容以及未來臺灣生物藝術發展的可能方向。

2014年,顧廣毅與TW BioArt臺灣生物藝術社群的部分成員,一同參與了開源(Open Source)生物藝術平台Hackteria與印尼藝術團體Lifepatch一起在印尼日惹舉辦的活動「HackteriaLab 2014」。活動為其數週,與會者是來自世界各地的藝術家、設計師、工程師與社會運動參與者(activist)等來自不同領域的人們。主辦單位規劃以當地火山、河流和熱帶雨林為主題的三大方向,帶領與會者實地走訪當地的自然環境,進行田野調查和樣本採集。除了自然環境的探勘之外,也參訪了當地大學的生物實驗室與藝術家工作室。所有行程結束之後,所有的參與者在一個臨時的空間中依照各自的興趣組成團隊,進行研究與創作計畫,數週後,在當地的藝術中心進行成果發表。

最令人興奮的,莫過於在臨時的創作空間中所凝聚起來的跨領域實踐能量,有些小組利用購自雜貨店的日常物件、廚具以及基本的生物實驗器材,自行搭建一個小型的生物實驗室,觀察與研究在雨林或河流採集到的生物樣本。例如利用自製的顯微鏡觀察河流中的微生物狀態,抑或是利用廚具、壓力鍋以及以食物材料(如馬鈴薯、牛奶等)自製的培養基培育自當地採集到的菌種,放置於於培養皿中觀察,透過自製的操作台與保溫箱控制為無菌狀態,讓菌種在適當的溫度中成長。也有小組針對穆斯林婦女所面對的性別議題進行計畫,創立了幫助婦女了解自己身體,以及自己動手製作性玩具的工作坊。數十個不同的計畫在短短幾週內自發性地組隊完成,快速地展開研究調查與實作。

這些項目都奠基在生物駭客、或是說DIY 生物學(Do-It-Yourself Biology)運動等開源的概念之上。這些概念的核心想法是執行生物科學中培養微生物、生物化學實驗、顯微鏡觀察等科技技術――這些技術本來大多是需要在大學或是研究單位的實驗室中進行操作――並執行相關科學研究或計畫的資源。然而在生物駭客的概念中,生物技術被從研究機構中的實驗室解放,技術不再只被科學家持有,一般民眾都可以透過網路學習,在交流之中獲取相關的知識與技術,並在自己家中建立生物實驗室去執行想做的計畫。這種有機會實作一些本來受到學術規範限制的想法,與駭客(hacker)的概念有了交集,某種程度上也形成了挑戰科學系統疆界的能量,具備了顛覆體制和重建系統的可能性。

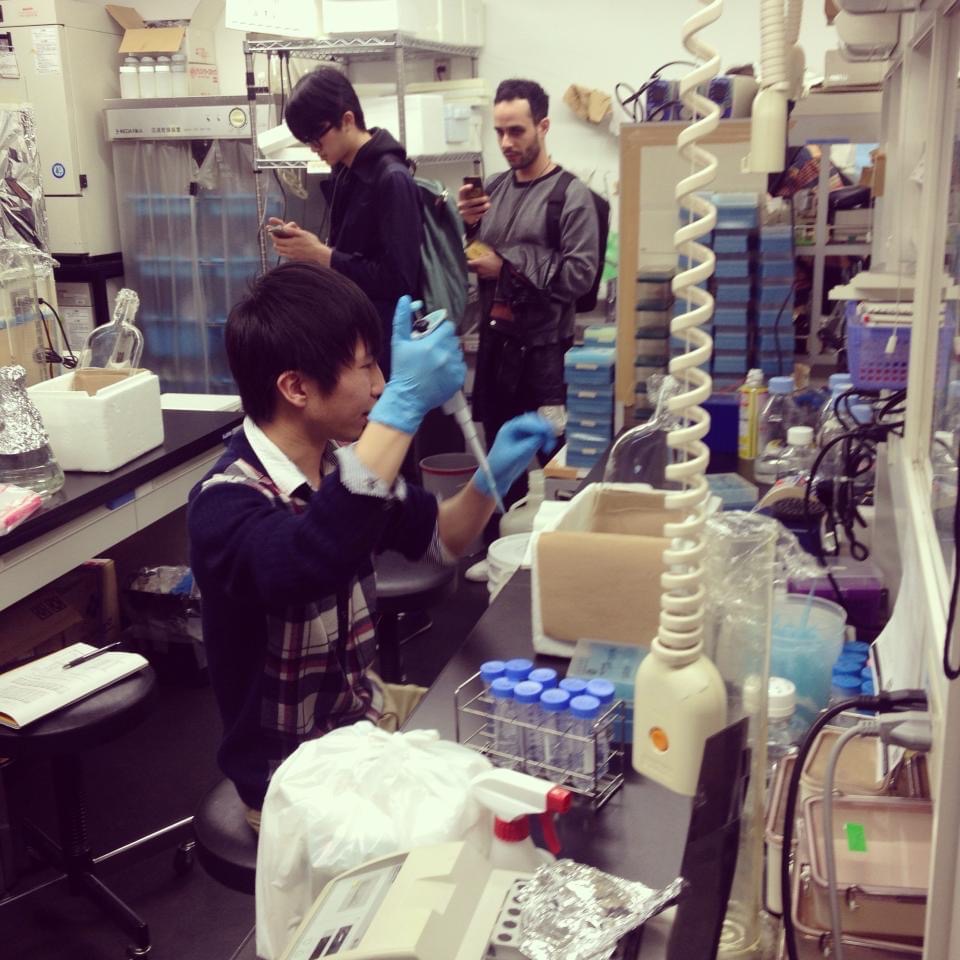

在印尼日惹舉辦的「HackteriaLab 2014」活動中,參與藝術家示範如何操作生物實驗。圖/顧廣毅攝影

在印尼日惹舉辦的「HackteriaLab 2014」活動中,參與藝術家示範如何操作生物實驗。圖/顧廣毅攝影

這樣的概念不只存在於一般公民科學的計畫中,也影響了許多跨領域創作的實踐者。而Hackteria就是一個這樣的例子,該組織中許多成員都是從事生物藝術創作的藝術家,在沒有大學與研究機構實驗室的前提下,藝術家只能透過這樣的方式自己搭建實驗室進行創作。這樣的模式蘊含著生物科技中權力結構的破壞與重建。然而,透過生物駭客模式的生物藝術創作,仍存在著問題,例如由於科學儀器的限制,當創作者想要進行更複雜的實驗時,仍然需要向大學或研究機構尋求贊助或協助,畢竟有些高端的生物實驗仍然相當仰賴特定的精密儀器,這樣的儀器是DIY 生物學運動的技術無法達到的,而這也是生物藝術實踐中容易遇到的問題。

在生物藝術的領域中,除了藝術家自製的實驗室外,現在也出現愈來愈多聚焦科技藝術領域的文化機構願意在組織內建立生物實驗室,提供機構內的藝術家技術和硬體支援。其中,荷蘭的Waag Society藝術與科技中心(Waag Society Technology & Society,簡稱Waag Society)就是設有實驗室的文化機構代表之一,除了建置有製造實驗室( Fabrication Laboratory,簡稱Fab Lab,包含基本的數位製造工具,例如雷切機、3D列印機等)之外,也有規劃設立所謂的開放式濕實驗室(Open Wetlab),也就是可以操作生物實驗的實驗室。

Waag Society在編制上有四個研究小組,分別為:製作(Make)、編碼(Code)、學習(Learn)和照料(Care)。製作小組是以DIY精神為核心,探討如何透過硬體、製造過程與材料研究社會與環境問題。編制在製作小組下的實驗室有:開放式濕實驗室、阿姆斯特丹自造實驗室(Fablab Amsterdam)以及紡織實驗室(TextileLab),這三個實驗室除了研究內容外也都各有實體空間。開放式濕實驗室可以做生物安全第一等級(Biosafety Level)1的實驗;自造實驗室具有雷切機、3D印表機、電腦數值控制(Computer Numerical Control)以及簡易電子電路儀器;紡織實驗室則是研究如何利用前兩個實驗室的資源,去製作織品設計與服裝設計。

在此,針對能夠進行生物實驗的開放式濕實驗室進行更多的說明,開放式濕實驗室裡面有許多生物藝術、生物設計以及DIY 生物學運動等公民科學計畫在進行。這也代表了裡面工作的包含了藝術家、設計師以及自造者(Maker)等不同領域的人們。這些人有些是Waag Society主動邀請來的專家,但除此之外,Waag Society也開放給所有人來申請這些實驗室,並在篩選後期望能吸引理念相近者共同使用實驗室。

Waag Society藝術與科技中心(Waag Society Technology & Society)的開放式濕實驗室空間。圖 © Waag Society Technology & Society

Waag Society藝術與科技中心(Waag Society Technology & Society)的開放式濕實驗室空間。圖 © Waag Society Technology & Society

Waag Society藝術與科技中心(Waag Society Technology & Society)的開放式濕實驗室空間。圖 © Waag Society Technology & Society

Waag Society藝術與科技中心(Waag Society Technology & Society)的開放式濕實驗室空間。圖 © Waag Society Technology & Society

這些實驗室除了有許多計畫在進行外,也會不定期的開放給一般民眾參觀,傳播知識。實驗室的風格十分接近於生物駭客模式,內部的很多實驗器材,並不是最高級的實驗設備,常常是二手、或是自己組裝而成的,有些甚至是類似廚房中常見的設備。例如培養箱是從農場得來的二手孵蛋溫控箱,無菌操作台也是自主搭建而成的。由於Waag Society樂於推廣自己搭建生物實驗室的精神,因此規劃了「生物駭客學院」(BioHack Academy)計畫,此計畫是一系列的教學課程,開放給世界各地對於DIY生物學運動有興趣的人參與,在課程結束之後,參與者將學習到如何在家裡建立一個屬於自己的濕實驗室。如此一來,一般民眾都可以藉由這個課程在家中自己操作生物實驗,而不必然需要具規模的機構所擁有的實驗資源。

開放式濕實驗室的資源也可以被使用於生物藝術家駐村計畫中,例如Waag Society加入由阿姆斯特丹藝術基金會(Amsterdam Fund for the Arts)每年所規劃的「三組協定」(3 package deal)計畫。此計畫讓給許多不同領域的國際藝術家進駐阿姆斯特丹一年。其中,生物藝術的項目為三個單位一起合作,分別是Waag Society、Mediamatic餐廳以及阿姆斯特丹自由大學(Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam),每年資助一位生物藝術家於阿姆斯特丹駐村。Waag Society在這個計畫中,提供藝術家開放式濕實驗室的設施作為資源,讓藝術家進駐內部進行創作。在一年的駐村過程中,藝術家會規劃成果發表,形式多為表演、工作坊、演講抑或是高互動性的展覽呈現。發表場地常在Waag Society的八角形會議廳舉辦,藉此將藝術家的創作計畫與一般觀眾連結起來,這樣的跨領域活動成為藝術、科學與一般大眾的橋梁。

早稻田大學尖端生命醫科學中心內部。圖/沈賓提供

早稻田大學尖端生命醫科學中心內部。圖/沈賓提供

metaPhorest在「C-LAB生物藝術實驗室研究案」之中被列為是學院中的生物藝術實驗室,在此範疇中則包含兩種類型:一種是藝術與設計學院中的生物實驗室,提供創作上所需的資源與技術;另一種就是像metaPhorest這種綜合型大學或是理工大學裡面的生物實驗室,用於進行生物相關的藝術研究或是創作實踐。metaPhorest創立於2007年,位於早稻田大學尖端生命醫科學中心生物實驗室中,是專注於探討生物/生物媒體藝術(biological / biomedia art)與生物藝術(Bio Art)的實踐與教學平台。metaPhorest的主要成員來自不同領域,平台主持人岩崎秀雄(Hideo Iwasaki)在早稻田大學擔任教授,他不但是位生物學家,也是位藝術家,專長為細胞分子生物學、時間生物學、藍綠藻晝夜節律、生物藝術與美學。平台的其他成員多為理工、設計與藝術相關背景,當中的成員福原志保(Shiho Fukuhara)與喬治.特梅爾(Georg Tremmel)也是媒體藝術與生物科學跨領域藝術團體 BCL 與生物科技社群平台BioClub Tokyo的聯合創辦人。

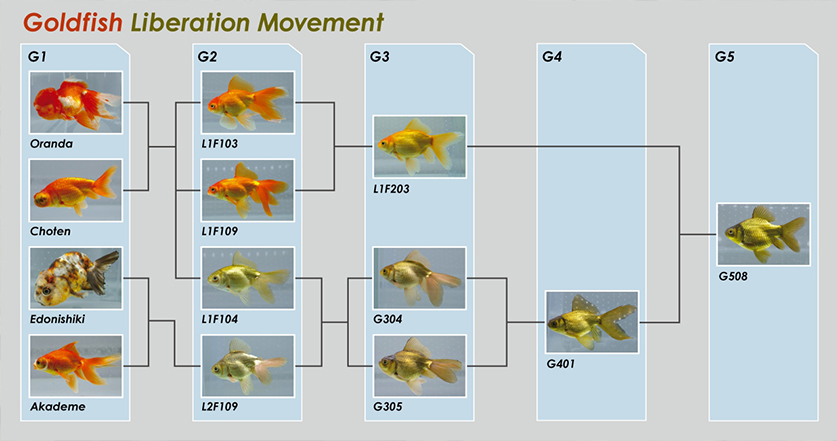

metaPhorest 成員的作品,除了專注於探討生物本身的美學之外,也透過藝術的手法去探問自然與非自然之間,以及人類試圖透過生物科技控制物種的倫理道德問題。像是BCL的作品《常見的花朵/白色顯現》(Common Flowers / White Out)試圖制定出一種策略,可以讓非生物科技專業的人都能夠去除已被植入基因工程植物中的基因,讓康乃馨變回原始的白色。其所針對的「藍色康乃馨」即是澳洲生技公司Florigene開發的第一批基因改造植物。BCL想透過這個作品扭轉人造的干預,探索商業與生物科技的道德邊界,並試著拋出疑問――除了植物之外,食品和其他生活產品是否也會為了單純的視覺效果而進行基因改造呢?另一方面,就算不是科學家,一般人有可能從轉基因2植物中去除基因,讓生物體重新擁有自我嗎?另一位metaPhorest的成員石橋友也(Tomoya Ishibashi)從2012年開始的長期計畫《金魚解放運動》(Goldfish Liberation Movement)也是依循類似的脈絡,嘗試透過人工選育3的逆向繁殖,解放因為人類尋求陪伴的控制欲而被豢養了1700年的金魚,找回牠們的原始野性與特徵。

石橋友也(Tomoya Ishibashi)從2012年開始的長期計畫《金魚解放運動》(Goldfish Liberation Movement)中的金魚家族樹狀圖。圖/石橋友也提供

石橋友也(Tomoya Ishibashi)從2012年開始的長期計畫《金魚解放運動》(Goldfish Liberation Movement)中的金魚家族樹狀圖。圖/石橋友也提供

2014年還是皇家藝術學院(Royal College of Art)碩士生的宮保睿透過系上交流之旅,參與metaPhorest的座談與交流。在參觀實驗室的過程中,發現metaPhorest 成員可以自如地使用尖端生醫中心生物實驗室中的高端器材,對於想要嘗試生物實驗或是生物科技的藝術家來說,這是一個很棒的機會,除此之外,也可以與實驗室的科學家直接交流,精進與學習硬體與軟體技術;而在教學與學術研究上,藝術家的思維可以與學校本科生或是科學家的研究交互影響,也許在學院中擁有生物藝術實驗室與教學平台,可以創造出雙贏的網絡、連結不同領域的人。

「下一個自然網絡」(Next Nature Network,簡稱NNN)被列為「推測設計為導向的思想實驗室」類別,透過推測設計的方法,建立思想實驗室或是推測設計平台,研究未來生物科技等前端科技與未來社會的可能方向,並與科學家合作設計出與科技相關的作品。NNN是來自荷蘭專注討論生物學與科技未來的國際網絡平台,談論的主題包含:食物未來與科技、動物議題、生態環保議題與生物科技等跨領域議題,除此之外也提供教學服務,以新的思維方式、工具和方法,扭轉大家對於自然與科技之間的思考與想像,並透過講座、互動式工作坊等方式帶領個人或機構進行學習。NNN的目標希望透過具有啟發性與趣味性的計畫、展覽、活動與產品來激發辯論,進一步探討未來議題。

NNN的創辨人柯爾特.范.門斯沃特(Koert van Mensvoort)集藝術家、哲學家與科學家的身分於一身,也是安多芬理工大學(Eindhoven University of Technology)工業設計系下一個自然研究室的主持人。該實驗室始於他們在部落格上發布與「下一個自然」主題相關的文章,由四到五位核心成員與不同的貢獻者去維運網站,2011年,他們發行了第一本書《Next Nature: Nature Changes Along with Us》試著以不同的主題與觀點去看待自然,反思科技可能成為我們的下一個自然。

NNN常以推測設計的方法與一般社會大眾產生對話,透過易理解的設計去連結重要的民生議題,進而帶領大眾去思考未來的可能性,像是呈現45道透過實驗室培養出來的肉類製作成的想像未來食譜《試管肉食譜》(The In Vitro Meat Cook Book),使用食譜的形式作為故事媒介,探索用實驗室培育肉類可能造成的「食物文化」,重新定義大眾對實驗室培育肉類與現今工業化生產肉類的看法。曾於「2018臺灣設計展」展出的《人類機器》(Hubot)則是透過16種想像的未來職業,探索可能的工作類別,探問該如何應對數位革命與機器人時代的來臨?拋出人類是否可以與機器人一起互助合作的思考。近期,他們把對未來的關注從食譜和職業拓展到生育議題,《育托邦》(Reprodutopia)是設計師與科學家的共同合作,以推想人工子宮的技術為概念,設計出未來人工子宮的樣貌,並促使不同文化背景的群眾對人工子宮的倫理道德進行思辨。

藉由觀察荷蘭生物藝術與設計領域的興起,可得知從古至今,荷蘭人一直在處理土地的議題、與海洋相抗衡,對於荷蘭人來說,他們一直都在與自然博鬥,依靠各種概念爭取生存的空間。另一方面,荷蘭政府提供藝術家與設計師相對優渥的補助,讓他們得以自由創作,這些綜合性的影響使得生物相關的藝術與設計在荷蘭蓬勃發展, NNN也與其他機構一起合作與交流,像是 Mediamatic餐廳、Transnatural Art&Design Label等。透過藝術與設計的方式去思辨,試著以推測作為方法與發酵的種子,橋接包含科學、生物學、醫學、社會學、人類學、哲學等不同領域才是其中最重要的思想實驗和實踐。