關於妖怪,以及妖怪的困境,或許可以從一場文學運動說起。

1960年代,世界文壇發生了一場隱密而狂暴的地震,震央就在拉丁美洲;這場文學史上稱為「拉丁美洲文學爆炸」的現象,將古老又令人戰慄的魔法吐息吹進西方文壇的耳廓,在那之後,「魔幻寫實」成為專有名詞,濃縮成世界文學史裡的一則詞條。這種迥異於西方國家的書寫風格或內在邏輯,對它們無疑是震撼彈;在臺灣,這種技法也頗受學院看重。

不過筆者曾聽作家盛浩偉說「相較於臺灣,西方國家並沒有這麼重視魔幻寫實」。某種意義上,臺灣之所以重視魔幻寫實,或許正源於臺灣被殖民的歷史與尚未徹底現代化的割裂,被殖民國家就像分離四散的兄弟,在彼此身上嗅出了相似的靈魂,那靈魂就像《百年孤寂》(1967)中,逝去者的鬼魂會不斷回來,像擺脫不掉的宿命,永遠控制這個家族。

就如古典希臘悲劇的核心精神:性格決定命運。所謂宿命,其實就是文化心理招致的歷史重演;人類終究並非理性的生物,並不總是謹慎地分析判斷,而是對環境投以試探,最後摸索出一套方便的生活邏輯,不斷重播,彷彿故障的單調裝置。這是演化經過無數時間摸索出來的睿智。當我們活在一套文化邏輯中,自然形成宿命,也就是永生不死的鬼魂。

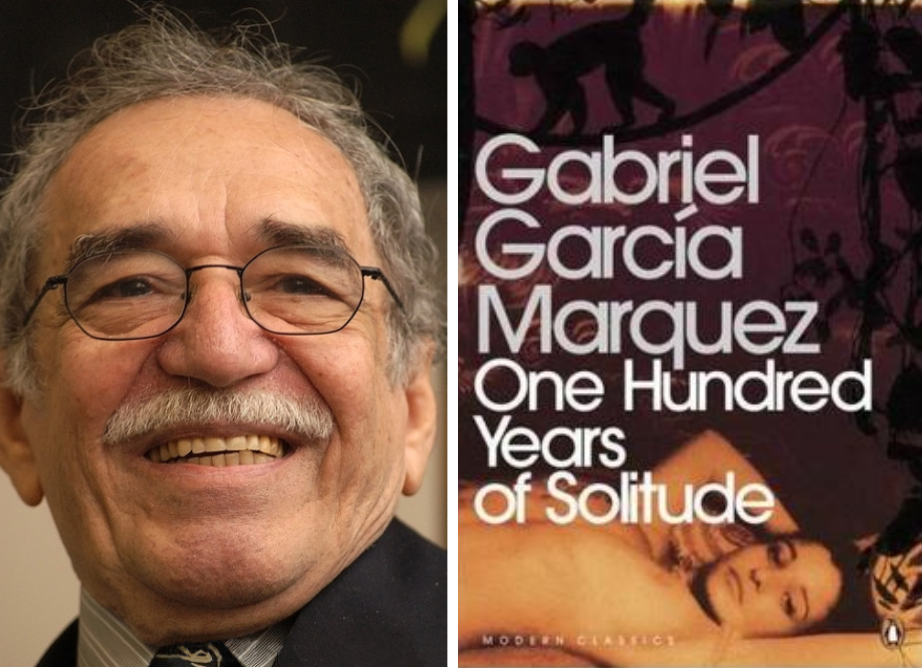

賈西亞.馬奎斯(Gabriel García Márquez)的《百年孤寂》是魔幻寫實的經典作品。圖/Jose Lara攝影、取自Wikimedia Commons

賈西亞.馬奎斯(Gabriel García Márquez)的《百年孤寂》是魔幻寫實的經典作品。圖/Jose Lara攝影、取自Wikimedia Commons

但這樣永生不死的鬼魂,竟能被殺死在當代都市裡;現代化就像新的魔咒籠罩著當代都市,這種新的生活邏輯透過城市構造自我複製,城市本身就成了當代幽魂的生產機器,既然空間被新的鬼魂盤踞壟斷,古老鬼魂自然就回歸無門,從此被放逐於鄉野。

所謂「新的鬼魂」是如何抵達當代都市,「古老鬼魂」又是如何被捨棄的?讓我們先回到賈西亞.馬奎斯的《百年孤寂》。在這部魔幻寫實經典中,老邦迪亞是馬康多的有力人士,馬康多是個新興小鎮,當時甚至還沒有死過人;政府派官員來到小鎮,想展現政府的權威,老邦迪亞卻闖進這位新行政官的辦公室,表明「這裡不需要法官,因為我們沒有事情需要判決」,接著把他扔出了城鎮。結果,新的行政官能在馬康多住下,是有力者允許的。那時,地方有自己看待世界的方式、自己的運作邏輯,通透一貫的權力被阻擋在外,官方必須馴服於地方才能容身。

日本殖民者透過都市規劃敲響現代性的鐘聲,從此改變臺灣居民的生活邏輯。圖為1911年臺南市區改正計畫圖。圖/Wikimedia Commons

日本殖民者透過都市規劃敲響現代性的鐘聲,從此改變臺灣居民的生活邏輯。圖為1911年臺南市區改正計畫圖。圖/Wikimedia Commons

臺灣早期社會也有類似風景。蘇碩斌在《看不見與看得見的臺北》(2010)一書,描述清國統治下的臺灣地方社會是如何的「不透明」。所謂的「不透明」,是指中國傳統的政治運作原則,本來就難以深入地方並進行科學化的管理,因此地方運作的邏輯並非官府制定,而是居民依各種環境限制自行發展出來的一套法則。不過,既然政府管理的能力有限,那地方秩序要如何維持,難道是一片混亂?不,秩序將由地方有力人士維持,如富商與仕紳;不透明的地方並不是無法地帶,只是「法」未必是大清帝國的法律,而是長期生活的當地人團結起的共識,並透過有力人士執行仲裁。事實上,清領臺灣的地方械鬥如此嚴重,不只是因為官府缺乏實質控制力,更因械鬥能一定程度地削弱地方勢力,甚至被官府視為抑制地方勢力的手段。由此可見,通透一貫的秩序並未由上而下進入民間,反而被民間拒擋在外,地方官將地方人士視為隱性的仇寇,放任械鬥以降低其對朝廷的威脅。

但這種尚未被統整的地方邏輯,正是魔幻的土壤;由錯綜複雜的主觀見解堆砌出來、不被科學方法所規馴的家族史,死者託夢,透過徵兆浮現的生命意義,鬼怪經過的痕跡,神靈附體,這些不能簡單地用「迷信」來解釋;任何解釋世界的方式能在一時一地成立,必有其道理,只是局外人缺乏解讀能力罷了。當西方殖民者透過船隻打破地理的界線,強行闖入異域,一方面將本有的信仰貶低為迷信,一方面卻將自身的魔魅輸出至殖民地;對臺灣的我們來說,若是對基督信仰的瞭解與同情更勝於傳統信仰,貶低廟會遶境,卻溫柔對待唱詩班,這究竟是因為基督信仰更「合理」,或是有某種看不見的力量強行運作造成,無疑是值得思考的。

最早敲響現代性鐘聲的,正是降臨這片土地的殖民者。日本時代,科學方法成為統治經營的工具,土地被精準丈量,都市規劃的觀念也被引入;但當日本殖民者能夠坐在辦公室裡決定城市該如何建設時,地方勢力已無發聲參與決策的權利,於是通透一貫的秩序終於由上而下,透過「都市」這個硬體進入民間,從此改變居民的生活邏輯。

為何說是硬體,而不只是政策?舉例而言,過去無廟不成村,廟宇一定是村落中心,廟埕是主要社交場所,許多夜市位於廟口,自有其發展的脈絡。但以都市規劃為名,過去廟宇被鏟平、遷徙,如此一來傳統的生活秩序該何以為繼?於是新的生活方式取代舊的,隨著公園、現代市場、百貨店、電影院陸續登場,過去魔幻的土壤趨於荒蕪,即使有新的魔幻,也不得不服膺於理性秩序的表象。甘耀明的魔幻寫實小說《殺鬼》(2009),前面有著磅礡震撼的想像,魔幻的光芒卻隨著故事推進到當代而逐漸泯滅,或許就是因為古老的秩序終將被現代性驅逐,不得不委曲於城市的角落,連辨識都有所困難。

甘耀明《殺鬼》(寶瓶文化出版)與巴代《巫旅》(印刻出版社出版)。

甘耀明《殺鬼》(寶瓶文化出版)與巴代《巫旅》(印刻出版社出版)。

本來,「現代」就有拒絕傳統的宣示意義。無論過去有多少國家、族群、傳統,都能用理性而均質的單一規格來貫通,全球化、地球村就是這種信念的產物。事實上,透過網路、媒體,當代的物質硬體確實具備滿足這種夢想的條件。對引領這一切的西方國家來說,他們早就透過高度經濟發展劃分出細緻的分工,將個人從傳統、家族中解放出來,供養個人的不是親緣,而是與城市硬體密切結合的種種制度。像魔幻寫實這樣仰賴族群史、地方性或文化心理的文類,西方國家自然感到驚奇,卻未必有共鳴。而臺灣對魔幻寫實的共鳴,或許正因現代化是殖民者強制介入的結果,臺灣並不是自覺地走向現代,現代與傳統還來不及正面衝突,就已面臨結果,這樣懸而未解的遺憾與不甘轉為魔幻的影子,傳統依然在現代的表皮下掙扎,期待破土而出。

我們或許會疑惑,現代性有什麼不好?這個浮華的當代世界正是現代性的產物,難道這不是個方便、舒適的世界?

但我們可以這樣問:方便、舒適就是至高無上的價值嗎?

2012年,荷蘭建築團隊MVRDV曾在臺灣策劃「垂直村落」的展覽,這個展覽從一個質問開始;該團隊在亞洲的幾個重要都市,如臺灣、上海、東京、香港、首爾等地拍攝街景,畫面裡都是櫛次鱗比的高樓大廈,而質問是這樣的:你能分辨這些街景有哪些不同嗎?

所謂的「現代都市」,或許真的是千篇一律的複製品,不只缺乏傳統,甚至沒有自我區隔的能力;在MVRDV提供的影像中,要是沒出現文字,恐怕還真的無法分別。正是這種與傳統告別的姿態驅逐了鬼神,但要是徹底失去傳統,我們還能從五光十色的霓虹燈中指認自己的歸所嗎?我們還能說自己是誰、認出自己的出身?

1762年的日本作品勝川春英在《列國怪談聞書帖》繪製的廁所精。

1762年的日本作品勝川春英在《列國怪談聞書帖》繪製的廁所精。

日本知名的怪談編輯東雅夫曾提出所謂「日式的恐怖」(Horror Japanesque),他認為日本的幽靈怪談等恐怖故事中蘊含著日本文化的根柢,也就是日本性。民俗學家柳田國男認為日本幽靈出沒於丑時三刻,西方鬼魂卻沒有這樣的限制,同樣是人死後化成的鬼魅,日本與西方就有了區隔,這僅是「日本性」的一例。日本所說的「妖怪」,西方直接音譯為Yōkai,就是肯定「妖怪」有著無法簡單直譯的複雜意涵,為了與容易造成誤解的Monster等語彙區隔,才採取音譯。這顯示日本「妖怪」一詞有著難以無視的文化特徵,這也是日本性。那麼,在臺灣妖怪蔚為風尚的當代,我們能不能透過臺灣妖怪去談所謂的「臺灣性」?

在《臺灣妖怪學就醬》(2019)中,筆者曾說神怪就是生活,是地方與族群的記憶,也是文化。以妖怪討論「臺灣性」,似是理所當然、合情合理的發展。但東雅夫所說的怪談不只是民俗學家記載的鄉野奇譚,還有作家的創作。

但作家個人所寫的怪談,真的能反映整個日本嗎?甚至像是泉鏡花所寫的〈高野聖〉(1900),情節疑似借鏡於中國傳奇故事〈板橋三娘子〉(編按:收錄於唐朝薛漁思《河東記》),這樣挪用中國古典作品的怪談要如何反映日本性?佐藤春夫的〈女誡扇綺譚〉(1925)發生在臺灣府城,且頗有向美國作家愛倫.坡致敬之意,這又反映出什麼日本性?但若是我們細讀,〈高野聖〉選了高野山僧人為重要視角,並顛覆了〈板橋三娘子〉裡將人變化為驢馬者的形象,這樣的詮釋,難道不是身處的文化鎔鑄為作者心中的鏡子,將同樣的事物照出不同的樣貌?要是真有人說這不是日本性而是中國性,反而令人發笑。〈女誡扇綺譚〉透過日本人的視角觀看「典型的中國故事」,正是這種觀看映照回來,重新界定了何為日本;無關故事發生的場景與致敬對象,主述者的位置決定了觀點的核心。

怪談或多或少都有古老的氣質,即使當代怪談亦然,這正是《百年孤寂》裡揮之不去的古老鬼魂。但當現代巨輪將妖怪驅逐在外,我們要如何與歷史聯繫?畢竟我們的城市甚至容不下歷史,古蹟會「自燃」,怪手也會「不小心挖錯地方」,讓歷史建築永遠消失在世界上。這個城市只需要單一規格的現代構造――這種想像總有一天會將古老的夢境蠶食殆盡,等回過神,我們已像是阿茲海默症患者,連該想起什麼都不知道,甚至無法區分自己與他人。

而探討「臺灣性」的眾多方法之一,正是為妖怪尋求重新在都市裡生存的辦法,賦予城市更多的可能與多樣性。當妖怪入城,以非日常的姿態穿梭巷弄,並不是要搗毀都市、讓古老的風暴佔領廢墟,而是尋求傳統與當代的媒合,現代性學會謙遜,不再粗暴地掃蕩一切,像迎賓一樣為古老記憶打開城門。

過去被主流厭斥的妖怪現今有了發聲的空間,臺北地方異聞工作室就出版了《唯妖論》、《尋妖誌:島嶼妖怪文化之旅》等書,圖為臺北地方異聞工作室一景。圖/王世邦攝影

過去被主流厭斥的妖怪現今有了發聲的空間,臺北地方異聞工作室就出版了《唯妖論》、《尋妖誌:島嶼妖怪文化之旅》等書,圖為臺北地方異聞工作室一景。圖/王世邦攝影

我們不能僅僅冀望於鄉野奇譚。因為在城市裡,能口述鄉野奇譚的人已逐漸凋零。但透過當代創作者的轉譯,妖怪得以穿透現代性的結界,在都市裡找到新的可能。其實這種嘗試並不罕見,只是未必進入大眾的視野;像李喬有許多作品脫胎自民間傳說,王家祥的《魔神仔》(2002)以科幻趣味將魔神仔解釋為矮黑人,甘耀明以想像與象徵重新詮釋鬼怪,巴代則化用巫術專業與文史考察到故事中;對熟悉臺灣創作的讀者而言,山精水怪不是什麼橫空出世的題材。

但近幾年間,臺灣主體意識抬頭,地方神怪逐漸引起文學讀者以外的大眾注意。行人的《臺灣妖怪研究室報告》(2015),臺北地方異聞工作室的《唯妖論》(2016)、《尋妖誌:島嶼妖怪文化之旅》(2018)、《臺灣妖怪學就醬》,何敬堯的《妖怪臺灣:三百年島嶼奇幻誌.妖鬼神遊卷》(2017)、《妖怪臺灣地圖:環島搜妖探奇錄》(2019)等書陸續出版,過去被主流厭斥的妖怪忽然有了發聲的空間,這種「鬼魂的迴返」,正是被現代性與殖民者剝奪了自我邊界的群體之抗議,為了治癒這種割裂,妖怪必須入城。

空總臺灣當代文化實驗場這次的「妖氣都市――鬼怪文學與當代藝術特展」,就是此一治癒進程的初步嘗試。策展人結合文學、當代藝術、插畫、雕塑、遊行等眾多妖異創作,以「妖氣都市」之名,打破都市僵化的現代性結界,歷史與當代並置,主流與邊緣同列,就如《百年孤寂》所說,「百年的事件濃縮在一起,使之在瞬間同時存在」,如此我們才能找回被遺棄的記憶,在繁華的霓虹幻影中,辨識出自己的倒影。