《塑料年代》(The Plastic Age)是藝術家Htein Lin的表演藝術作品:他用塑膠薄膜將自己包起來,手裡拿著一支被鐵絲網纏繞的畫筆,走在仰光的街道上。一位友人拍下他的影像,把照片放上《Tharapu Journal》,並於一旁附上簡介詳述該作品的創作動機,暗示塑膠膜限制了Htein Lin的行動能力,以及鐵絲網纏繞畫筆的意涵。藝術家在1996年進行表演時,仰光正同時經歷軍政府統治下的艱難時期與藝術的復興。1

若沒有這張照片,Htein Lin的表演將不會留下紀錄。在緬甸逐漸走出金融災難的黑暗期、走向國際社會之際,當地的藝文圈也渴望文化變革。當時審查制度滲透生活中的每個層面,電話和網路的使用被嚴格控管,通訊速度緩慢無比;書籍、繪畫、歌詞在出版、演出、公開展示前,全都必須經過正式的審查程序;國家政策則推廣風景畫、肖像畫、傳統音樂和舞蹈。表達意見的形式該進行有意義的轉變了。

平面攝影利於傳播,也能捕捉音樂家和藝術家演出時真情流露的瞬間。攝影本身促進了表演的行為,因為攝影產生的影像自成藝術品,成為被凝結的一瞬、藝術史上的紀錄。

沒有紀錄文件的話,事情真的發生過嗎?談到緬甸的藝術史,人們總為表演藝術和龐克音樂的先鋒到底是誰而爭論不休。檔案資料找尋不易,有些文件也不敵仰光的熱帶氣候而損毀,在2014年之前,冷氣對當地人來說都還是奢侈無比的東西。緬甸其他地方能提供的史料更少,不是根本無法取得,就是當地能夠保存、保護這些資料的資源遠遠不及該國的文化首都仰光。

Po Po在他首次被記錄的表演《藝術家的肖像作為展示者》(Portrait of the Artist as Exhibitionist)中,躺在自己展覽中心的一塊白布上。他形容這場表演:「一幅(被擺在地上的)畫作變成立體的人,它是實際存活的。」他的身體變成藝術作品,那場表演的照片證明這場演出真的發生過。Po Po在1995年前的表演只存在於他的記憶和素描本裡,沒留下影像紀錄,也因此一般普遍將Htein Lin的表演視為緬甸藝術史上第一個當代表演藝術作品。2

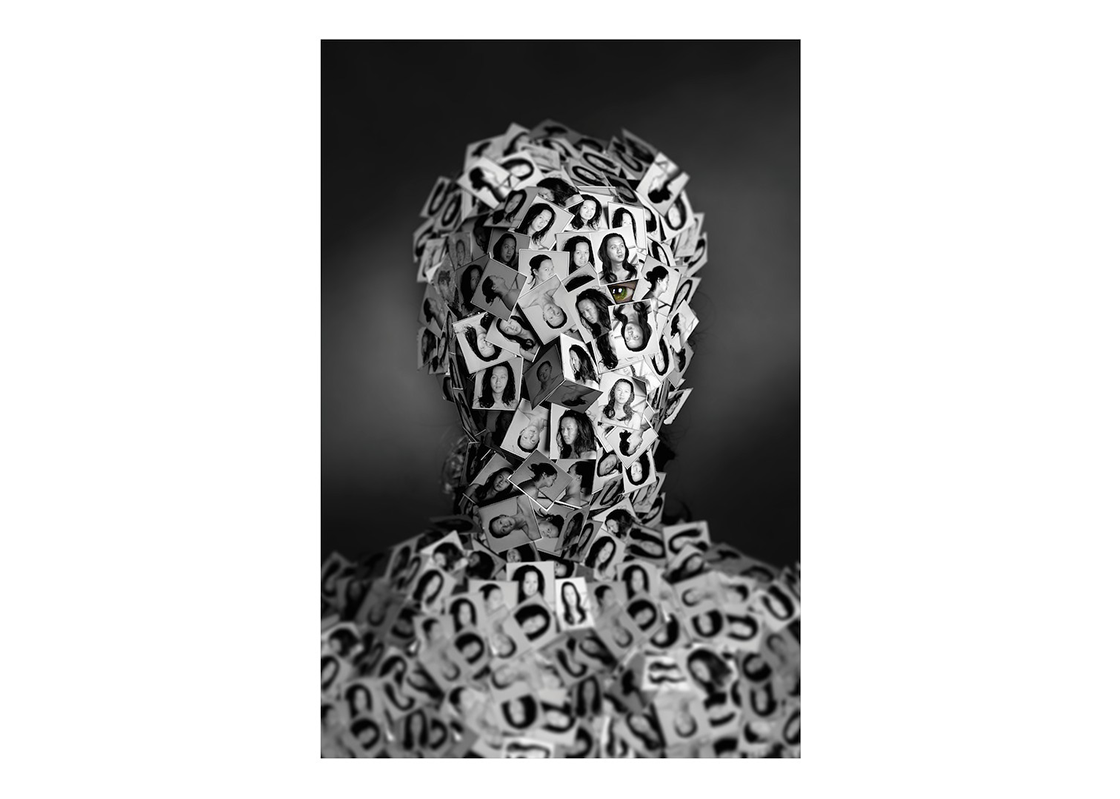

Thurein,《Mrat Lunn Htwann》,2013,彩色輸出、木板,36×48 吋。圖/藝術家提供

Thurein,《Mrat Lunn Htwann》,2013,彩色輸出、木板,36×48 吋。圖/藝術家提供

1990年代開始的20年間,許多人氣創作歌手和音樂人開始嶄露頭角,在私人錄音室錄製熱門金曲,小規模發行卡帶和CD給支持者聽。他們的肖像照成了言論自由的象徵,他們的歌詞是避免激怒審查委員會的詩句和暗號,這些委員們嚴禁任何暗示性、自殺、毒品、酒精、民主或翁山蘇姬的字句。藝術家的肖像和表演本身成了反抗的行為,藝術家則透過歌曲體現了自身所宣揚的價值觀。

ACID是緬甸早期的知名嘻哈團體,創團元老Anegga談到軍政府帶來的恐懼時,提及當時他認為自己身為音樂人有發聲對抗的義務,冒著生命危險也在所不惜。他解釋道:「我們是那些無法發聲的人的聲音。我們必須勇於發言。」3

由於大型表演場地、酒吧、餐廳有引來當局關注的風險,地下演唱會、表面上看起來無害的臨時演出因而變成常態。親友和觀眾拍下的照片成了仰光這些即興演唱會唯一的紀錄。2000年代中期,喜愛音樂的外國遊客拍下緬甸當時最紅的叛逆年輕歌手,這些生猛有力的照片讓當地的龐克、嘻哈、獨立搖滾音樂受到國際矚目。

在樂壇持續成長茁壯,持續受到國際矚目的同時,藝術家也一邊進行實驗,探求表演藝術的可能性。他們讓自己的身體成為藝術品,透過行動和物件表達他們最根本的思想。許多緬甸藝術家從學生時代就開始習畫,但表演藝術開創了一條截然不同的路。當時傳統繪畫亦遭到嚴格審查;不但禁用紅色,裸體和政治等主題更是不被允許。表演藝術的呈現方式令人費解,成功躲過被審查委員會和警察識破的命運。表演藝術不受地點限制,幾乎不需任何物件就能演出,人人皆可在不花大錢的情況下進行。

藝術家走上街頭。Nyein Chan Su頭頂著鐵絲繞成的球體走在大街上。Jeuko San結合自身的小提琴技巧和進行實驗的渴望,成為該國最早結合表演和音樂的實驗音樂家之一。知名抽象畫畫家Aung Myint在自己的Inya藝廊舉辦表演藝術工作坊,鼓勵年輕的一代以這種形式自由的媒介進行實驗。

這些活動大都被相機記錄下來,拍出的照片為這些藝術家不同的實驗階段寫下歷史,促使更多人注意到緬甸的藝術景象,也連結了全國各地的藝術家。表演藝術幫助藝術家自由表達他們的苦痛、個人的勝利和提問。接下來好幾年的時間裡,相關的攝影作品都以詮釋者、翻譯者的角色持續幫助他們表達自我。

2013年,緬甸開始開放國際金融和國際交流,多位表演藝術家受邀至東京、新加坡、柏林等地參與海外的大型展覽。龐克、獨立搖滾、嘻哈歌手開始在仰光等國內主要城市公開演出,MTV節目也到緬甸報導他們的發展。越來越多人對當地的音樂產業感興趣、投入資金,藝術界也跟著從平面攝影轉移到數位影音,以完整記錄各種表演和訪談、聲音,全面記錄仰光和緬甸藝術界蓬勃發展的樣貌。

然而,平面攝影在藝術家之間並未退燒。照片仍是記錄展覽、事件、表演的重要文件。當攝影作品變成有價的藝術品時,其角色也迎來重大轉變。各種演出開始變身為風格強烈的影像,被印在高級的大型材質上,於全球各地的藝廊和展覽中展出。平面攝影作品變成可販售的物件或紀錄,能為藝術家賺進足夠的錢,讓他們能以表演維生。

Ma Ei,《草莓片》(Strawberry Piece),表演,2016年於瑞典斯德哥爾摩Fargfabriken。圖/藝術家提供

Ma Ei,《草莓片》(Strawberry Piece),表演,2016年於瑞典斯德哥爾摩Fargfabriken。圖/藝術家提供

Ko Latt,《自尊情結》(Superiority Complex),表演,2016年於Goethe Villa。圖/Nathalie JOHNSTON攝影

Ko Latt,《自尊情結》(Superiority Complex),表演,2016年於Goethe Villa。圖/Nathalie JOHNSTON攝影

緬甸官方在2015年終止審查制度時,當地的音樂人和藝術家已在全世界被拍下成千上萬的照片,但仰光的藝術圈生氣蓬勃,各種令人驚豔的新音樂和藝術形式欣欣向榮,在此地拍下的照片尤其多。年輕一輩的藝術家開始自己創造機會,越來越多人可以過著創意生活。當局解除對大型通訊公司的禁令是造成此一現象的主要原因,因為大公司讓大家都買得起SIM卡和智慧型手機,而每一支智慧型手機都有相機功能。高速網路和上百萬的社群媒體使用者意味著大量的影像被即時分享,追蹤全國各個角落的藝術生發。

然而,有關當局仍在持續監控中。祕密警察(又稱特別支隊〔Special Branch〕)到各個場地以智慧型手機拍下未經申請的活動和事件後稟報政府相關單位。《電信通訊法》第66條d款生效後,所有照片和狀態更新都受到相關單位嚴密監控:「任何使用電信通訊網絡勒索、脅迫,不當限制、詆毀、干預他人,造成不當影響或威脅者,得處三年以下有期徒刑或併課罰金。」4

有些藝術家已經開始利用平面攝影和社群媒體進行表演性的藝術計畫,以此表達自身的異議。表演藝術家Emily Phyo過去曾為新零派藝術空間(New Zero Art Space)學員,她決定用Instagram作為發表表演照片的平台。她於2015年1月1日至2016年1月1日間連續365天,每天拍攝一位不同的人,並將照片放上她的IG帳號@emily_phyo;她的目標是和越多不同的人聊天越好,並且在替他們拍照的時候認識他們。Emily在仰光的市場經營一間小裁縫店。她用捲尺遮住被攝者的雙眼,賦予他們一種表面上的匿名性。捲尺在鼻樑上標出被攝者的年紀,她再利用標籤功能記錄他們的名字。這一年對緬甸來說是很重要的一年,因為這是該國第一次舉行普選並成功轉移政權,Emily Phyo的紀錄充分呈現出緬甸形形色色的人、手機相機的方便性和連結性,還有表演藝術從平面攝影文件走向數位傳播工具的轉變。5

平面攝影將在緬甸持續進化,這種有用的表達和記錄形式在當地有時有利可圖,有時卻會造成犯罪。最近才得以擁有相機的一般大眾尚未全面體會到攝影的作用。現今重要場所、教育性質的工作坊和中心已對仰光民眾開放,傳播、分享資訊的便利性必將促使緬甸藝術家和音樂家建立起自己的網路。在緬甸飽受內戰、移民危機和各種歧視之苦的同時,全世界將繼續對這個國家投以驚異的眼光。平面攝影將如何讓藝術家在轉型社會中活躍?音樂人將如何利用照片讓他們的音樂和影像推廣到全國各地?媒體是否會接受這些藝術家與他們的作品,讓藝術性照片的力量等同記錄性照片的力量?持續演變的情勢和時間將告訴我們答案,平面攝影也將在其中扮演行動者和媒介的角色。