Driving along the road on the right past ground control as one exits Matsu’s Nangan Airport terminal, we veer into an untrodden path in the forest and find ourselves inside a concrete underpass beneath the tarmac at the southern end of the airport’s runway. The leaves rustle past the windshield as the car makes its way through a narrow pass. “Sure this the way?” I asked. “Indeed, it is. Next time we will come on foot. It’s like crossing a tunnel,” replied LIAO Yi-Mei of the Cultural Diversity Studio. With every twist and turn, the path to Stronghold 26 mirrors my impression of the Matsu Islands as a whole. There’s always some new aspect of the place I see on each visit, and beyond the layers of camouflage, things are not necessarily what they seem to be. And beneath the cover of vegetation, more puzzles await.

It’s been more than two years since I first visited the Matsu Islands. Before that, my impression of Matsu was limited to an account given in our geography textbook—that it’s a distant island up against the enemy line, sharing the same history as Kinmen. If I may claim to have any ties with Matsu, it’s that my father was stationed here for his military service. So not knowing a whole lot about the place, I was surprised to discover that the local dialect was not Southern Min, like Kinmen, but sounded more like those spoken by distant Cantonese relatives. Furthermore, the architecture is in the Eastern Min style, and the culinary culture and flavors differ from Taiwan main island. After a moment savoring the view of derelict bunkers set against the unbroken expanse of sea and sky, I suddenly think of the repressive atmosphere and fearfulness of life on the frontline, separated from Communist China by just a swath of sea. On Matsu Island, slogans like “Rest upon your weapons and wait for the dawn of battle,” or “Islands of a shared destiny,” can be seen inscribed in relief. It also highlights a curious relationship that shapes the tight-knit communities and its inevitable history with the military. Various conflicts and intertwined emotions shape my conception of Matsu. As I make each journey here for different reasons, I gradually unfurl each layer and uncover every aspect of Matsu, and gradually come to understand its sophisticated appeal. Battlefield culture, geopolitics, and intricate relationships and stories always surprise me. Unlike Kinmen, which was also on the frontlines of battle, the fight never came to Matsu. All the same, it was subject to the same protracted military armament and combat readiness routines, and a sense of uncertainty manifesting itself in all aspects of the island’s development.

A friend once joked about the three houses of Matsu’s poverty line: one in Matsu, one in Taiwan main island, and the third in China. After the civil war of 1949, Lienchiang County was divided into two: the part which the government of the Republic of China controls includes 4 townships and 5 major islands (Nangan, Beigan, Dongju, Xiju, and Dongyin), as well as 36 islets. The other part of Lienchiang county is much more populous and belongs to the Fujian Province of the People’s Republic of China. On a clear day, one can see the wind turbines on Huangqi Peninsula on the other side with the unaided eye. Matsu is just 9 kilometers off the coast of mainland China but is 211 kilometers from Taiwan. It’s about 7 hours by sea from Keelung Harbor in northern Taiwan to Matsu’s Nangan, while a boat ride from Matsu’s Beigan Baisha Harbor to Huangqi in Fujian takes 25 minutes after the implementation of the Mini Three Links. Every year in the tourist high season of April and May, a great influx of visitors occurs. Most of them prefer the 50-minute flight from Taiwan, but since it is also fog season, flights get canceled and the handful of convenience stores on the island are often overrun with hungry passengers. Besides people, supplies are also delayed, rearranged to being transported via waterways.

Matsu’s coastlines are often planted with vast areas of sisal for camouflaging military installations, which serve as an important shoreside defense. Photo by WANG Hsuan

Matsu’s coastlines are often planted with vast areas of sisal for camouflaging military installations, which serve as an important shoreside defense. Photo by WANG Hsuan

During the Ming Dynasty, Matsu was a Chinese coastal fishing settlement, and the remains of a stone carving commemorating the successful defense against pirates is still preserved on Dongju Island. Matsu’s 4 townships and 5 islands are surrounded by sea, and to provide adequate defense capabilities, almost all islands have strongholds built along the shoreline. On the administrative seat of the County, Nangan township, there are as many as 95 military strongholds. These strongholds are often built as bunkers that conform to the terrain, mostly connected with tunnels and fitted with machine guns and other machinery. Larger strongholds featured dormitory buildings above ground or spaces for assembling and training. The structures vary in construction with the terrain, some by excavating mountainsides, and some built as reinforced concrete structures covered with soil and planted with sisal, a common plant, for camouflage. Besides offering visual protection, sisal’s leaves, prickly like pineapple’s but longer, protect against incoming paratroopers. Bunkers are mostly situated by the sea, against the backdrop of the sea and sky. From the perspective of tourism, they are perfect spots for checking in on social media. But if we look back to the period of military stand-off between governments, these military installations are the first line of defense, always on alert with no room for error. At night, soldiers stand guard at the posts by the sea, where the “ultimate view” can suddenly become a soldier’s “ultimate resting place.” This is because one must stay vigilant and overcome sleepiness while looking out for the ambush of “sea ghosts,”1 who can turn a glimpse of the sea and sky into a quick death.

Following the abolishment of the military administration in 1992, most of the military installations except for a few strategic ones have been overrun by vegetation over time. Similarly, Matsu itself has been transformed, from a role of frontline defense to a locus of exchange. In 1999, the Matsu National Scenic Area Administration was established. In 2000, the Mini Three Links saw Matsu become a busy outpost for those traveling between Taiwan and China. From standoff to exchange, Matsu has pivoted to a place of tourism, making up lost revenue from the massive reduction of troops. Unbound by convention, the island has also contemplated issues of setting up a gambling zone for bolstering the economy. Yet the inhabitants, through communication, discussion, and inter-generational dialogue recognized the extremely limited resources of the island and chose instead to work from their privileged position and find their own sustainable path towards growth. After more than 20 years of welcoming open exchange, Matsu Islands is experiencing a new “demilitarization” phase: untangling the processes of warzone conditions, which shaped its unique historical trajectory and culture, to reconstruct a methodology of social communications. Being a potential World Heritage site, undergoing numerous regeneration of historic sites, and located on the East Asian island chain (the first island chain) in the Cold War era, Matsu’s continued debate on topics such as preserving its military heritage, its collective military/civilian memory and narrative from the military administration period, and the revitalization of decommissioned military buildings, all seek to find a win-win or even an all-win scenario between native historical context and regional revitalization.

Matsu has a tight-knit interpersonal network that can be traced back to past eras. Stepping on to this territory of Taiwan at the fringe, right next to mainland China, one finds numerous military mottos in relief such as “Islands of a shared destiny,” “Reconquer the Mainland,” and “Rest upon your weapons and wait for the dawn of battle,” which took us to the island’s wartime past faced by its inhabitants. Matsu was a remote fishing village on the coast of eastern Fujian province in China. After the Chinese Civil War, the Kuomintang government retreated to Taiwan, and Matsu became the frontline against Communist China. Up until 1992, before the abolishment of the military administration, the island has undergone decades of military armament. In the example of Nangan, the natural geographical conditions of the coastline meant that inhabitants lived mostly in the bay area for fishing and navigating. In the military administration period, the coastline became the frontline of the war, and private lands were even expropriated for military use. Forts were set up to protect the island’s bays, from Fuao Harbor, Qingshui Bay, and Jhuluo Bay’s Stronghold 01 (Victory/Shengli Fort), a total of 95 military strongholds were built along the shoreline, creating a figurative iron wall.

Back then, inhabitants of Matsu cannot freely travel to Taiwan and needed to apply for a special permit. Matsu was even given its own regional currency.2 “Guard secrets and thwart spies,” and “Military and civilians as one” are also commonly observed mottos. Matsu locals form their own civil defense force, and everyone, male or female, is on reserve. Every night after curfew takes effect in the villages, travelers must present a passphrase for passage. The phrase was regularly changed to guard against infiltration by enemy spies. Military and civilian cohousing is the norm, and private properties were even expropriated for military use. Fishing which was a means of livelihood in the past becomes restricted by the state of heightened alert. Besides mixed living, local businesses were also impacted, transforming themselves into grocery stores, eateries, military stationery or supply stores, and entertainment venues made changes to cater to the primary consumers, the soldiers, such as billiards, karaoke, and internet cafes.

Scene of Matsu’s Andong Tunnel on Dongyin Island. Photo by Erica Yu-Wen HUANG

Scene of Matsu’s Andong Tunnel on Dongyin Island. Photo by Erica Yu-Wen HUANG

Under the pressures of the military administration, Matsu’s collective memory is unspoken, with many indescribable and unspeakable complex emotions. After the abolishment of the military administration, Matsu again faced issues of changing social structure, vastly reduced military personnel, and transformation of industries. Due to the highly integrated nature of communities, communications on public issues led to friction across generations, and a period of tension ensued. As an outsider, my exchanges with local youth, whether the ones returning from abroad or the ones who settled here attracted by its charms, have been engaged to initiate understanding and to accommodate each generation and group within the community, leading to renewed dialogue. There are the groups such as Cultural Diversity Studio, which spent years cultivating local cultural practice; Matsu Youth Development Association, which dedicated two years to renovating Jhuluo Elementary School and set up an office in Matsu this summer; Café Nanmon, which I always stop by on my hike to Renai Village (formerly known as Tieban Village); Good Dong-Ju, which offers traditional Lees (residual yeast from winemaking) dishes presented by 11 local women in their home cooking styles; and Dapu plus, which took on the task of revitalizing Dapu Village on Dongju Island. Along with governmental agencies, civilian groups have taken up the conversation, rediscovering Matsu’s charms and value.

From battlefield to tourist destination, Matsu receives tens of thousands of visitors who come to see “blue tears.” Blue tears are formed by a bloom of tiny, bioluminescent creatures called dinoflagellates, although there are countering theories on the phenomenon.3 On my first visit to Matsu, I also hit the tourist trail at nighttime to “see tears” in Beihai Tunnel. The tunnel is free from light pollution, so as we rowed along on the boat, the guide asked us to dip our paddles in the water, which revealed the blue tears. However, the tourists’ excitement at the scene is uncontrollable, and from the view of the dinoflagellates, it resembles a human invasion so that they illuminate the waters frantically in hopes of scaring off the intruder.

The military heritage of Matsu has given me much thought on ecology, as the Beihai Tunnel built originally as part of the military’s Beihai Project became a gathering place for blue tears. Many coastal security stations are hotspots for “seeing tears” or “chasing tears,” due to limited human activity (vacated by military garrison with no ships or fishing activity nearby) and least light pollution at night. As the waves hit the coral reefs along the coast, countless blue lights flicker and light up the sea in a unique glow. I was also brought back to the memories of a project from 2019 on Finland’s Örö Island. Örö shares many qualities with Matsu as a military outpost, and due to travel restrictions and heightened alert, it preserved many species of life such as butterflies. After it was decommissioned, fewer people came to the island, leaving wildlife to flourish. War is dangerous, but for other species, human beings are even more treacherous. When humans recede, other species find more space to grow.

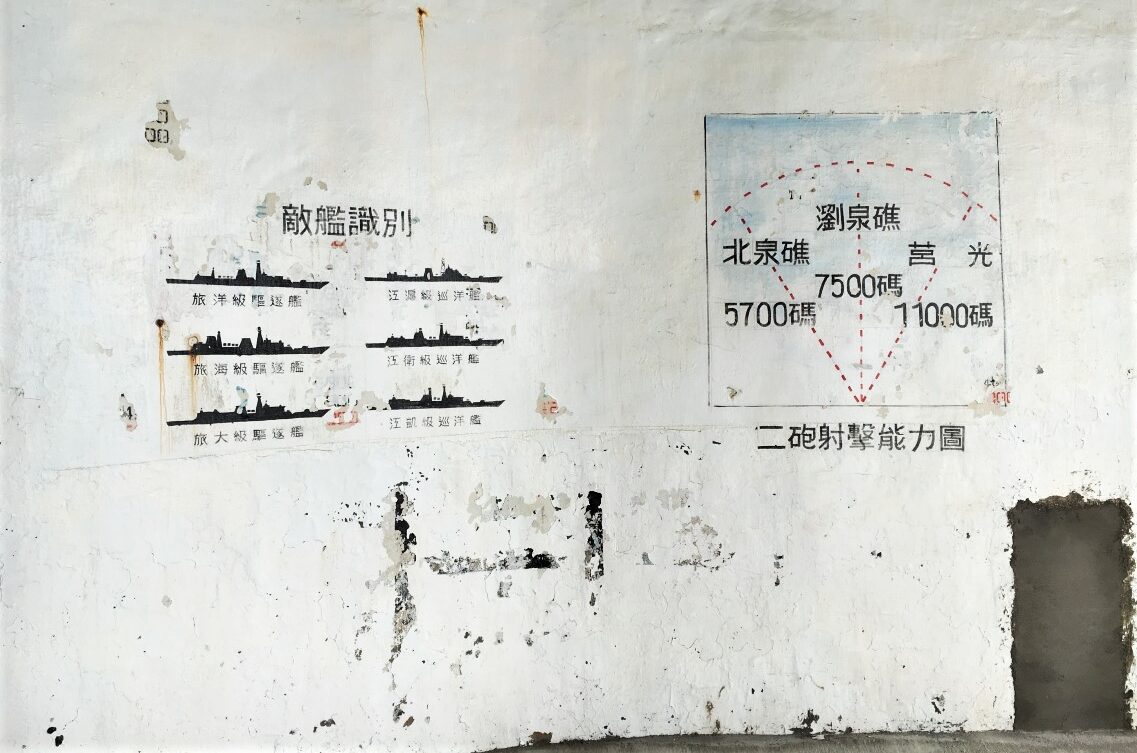

A mural at the Dahan Stronghold in Nangan’s Tieban Village indicates the features by which enemy ships can be identified. Photo by Erica Yu-Wen HUANG

A mural at the Dahan Stronghold in Nangan’s Tieban Village indicates the features by which enemy ships can be identified. Photo by Erica Yu-Wen HUANG

Matsu’s strongholds, which served as the first line of naval defenses of the islands, not only remain the military heritage, preserving the original appearances of wartime culture and embodying its history, but also present new possibilities as the island opens up to new possibilities. The Thorn Bird Coffee Bookstore, for example, is located at Stronghold 12, while a backpacker’s hostel is run by native youth in what was once Stronghold 55. The first stage of demilitarization is preserving original features, installations, and exhibitions of historic sites. The second stage is repurposing installations and transforming spaces into experience centers with original qualities and new functionality. Matsu’s military heritage preserves the many layers of history in present space, leading to the third stage, reinterpretation and regeneration of the Gazing Fortress Matsu Project, which introduces design and cultural thinking in its approach towards experimentation and dialogue on architectural spaces, historical texts, social relationships, and relationships between human and the environment.

I visited Matsu in February of last year when the pandemic began, and the solidarity of the local community was reassuring. The “Guard secrets and thwart spies” drills have made this a bastion for disease control, with everyone keeping watch over each unmasked neighbor or each arriving new face. In the latter half of the year 2020, I joined the Gazing Fortress Matsu Project, visiting again in the summer for field research as well as for document work on strongholds 26, 53, 77, and 86, as part of the Architecture reinterpretation Project. Along with other participating architects, artists, directors, and photographers on the team, we conduct interviews, collect documentaries, and create new works, experimenting with new methodologies as we train our gaze on the island. To me, my time in Matsu has been like a peach blossom spring, or a discovery Shangri-la, if you will. I likewise wish you luck on a journey of discovery, to be able to see a world of fascination beneath the appearances.