走入位於安坑如意街市場內的「暗坑文化工作室」,約莫二至三坪的小空間整理得十分舒適;古董菜櫃裡收納已有百餘年歷史的線裝古書、幾尊陳列的無主神像、日本殖民時期的和式矮茶几擱置地毯上……若不細究這些古物的緣由與歷史,這裡看起來就只是一間充斥著「生活感」的尋常工作室。生活感,這恰恰是暗坑文化工作室執行長吳柏瑋對於「文化」所下的最佳註解。雖然安坑(安康)是所在地行政區域上的正式名稱,但在柏瑋的父執輩,使用「暗坑」這個名字,才是在地人百餘年以來一直傳承下來的在地認同,亦連結起過去人們生活的時空。也因為如此,吳柏瑋選擇用「暗坑」這個名字來做為工作室的名稱,並從2016年開始投入耕耘地方文化工作。

對於一些人來說,從政經歷是他們對吳柏瑋的最初印象,他曾擔任過議員助理,也在2018年代表樹黨參與選舉,但從事政治的初衷,其實是希望能夠為地方留下一些可以永續發展的文化資本;他認為,在臺灣要做文化與環境的保護,最直接的方式就是從政,才能較有效地從法源上進行改變,獲取行政或資源上的挹注。

從2016年開始,他與工作室的團隊也一直思考如何「介入」地方文化。吳柏瑋一開始摸索過很多方式,原先成立了印象工作室,希望用「城市印象」的概念,使用影片或照片的形式,用視覺來幫助大家更認識這個地方,這樣的方式雖然在視覺上看起來是有吸引力的,但要更深入地去闡述一個地方的特色,或城市百餘年來的樣貌時卻無法更加深刻,於是他開始思考其他可行的方式。2018年,也是在代表參選的那段時間裡,他開始投入比較大型的文資倡議活動,例如古厝與樹木保存,當中也遇到很多挫折,他坦言衝擊最大的是曾經有民眾當眾指責他:「墳墓沒有票,不要作秀啦」,「我回答她說我不能對不起祖先,雖然沒有票,但我在乎。」1 柏瑋認真地這樣說。

當「選票」成為凌駕一切之上的考量時,利害關係就會變得太過於明確,但在臺灣,文化保存議題並不是普羅大眾都認同的價值,而這正是文化保存一直以來所面臨的困境。因此,吳柏瑋選擇用另一條路徑去告訴公眾,提出「文化保存是有利可圖的」想法,藉此來消融在地居民人對文化保存議題的誤解與抗拒。

「我們這些行動是在做一種社會擾動,擾動臺灣的人民去重新整理和建構價值觀。這是為什麼文化必須是持續的、甚至是可獲利的,要讓更多的人知道文化保存對於整個地方、乃至整個臺灣都是有公共性與益處的事情。」吳柏瑋這樣說。這催化了團隊開始轉換一種更柔性的方式進行倡議,讓地方的居民開始意識到文化保存可以帶來實質性的利益與反饋。

從2019年行政院宣示該年為「地方創生元年」2 後,地方政府開始更加重視屬於地方的特色,鼓勵年輕人能夠回到家鄉創業與生活。為了幫助更多的年輕人投入,吳柏瑋也開始思考設立公司的可能性,於是庄頭文化公司因運而生。有了公司的行政與運作經驗,可以承接標案,合法取得收益,再把這些資源真正的挹注在這些擁有熱情與文化保存使命感的年輕人身上。

由於過去團隊在處理文化保存的議題上,認知到文化必須回到如「庄頭」這樣一個單位,因此採用「庄頭」作為公司的名稱。每個庄頭都有其特殊的文化,光是新店與安坑分別隸屬與泉州移民與漳州移民的脈絡,在這樣的脈絡底下兩地設有大大小小不同的庄頭,都有屬於這個地方的記憶與認同。吳柏瑋表示:「我們希望以『庄頭』為名,讓每個地方的庄頭的年輕人回到自己的故鄉的時候,都能夠大聲的說出自己的故鄉。」

柏瑋在工作室中收藏了許多老件,包含百餘年歷史的線裝古書。圖 © 臺灣當代文化實驗場,許?倩攝影

柏瑋在工作室中收藏了許多老件,包含百餘年歷史的線裝古書。圖 © 臺灣當代文化實驗場,許?倩攝影

柏瑋認為,許多文物若僅能遠觀卻無法親手碰觸,與人的距離只會越來越遙遠,因此所收藏的神明衣飾,他也希望大家能透過拿在手中端詳,更細緻的觀察認識。圖 © 臺灣當代文化實驗場,許?倩攝影

柏瑋認為,許多文物若僅能遠觀卻無法親手碰觸,與人的距離只會越來越遙遠,因此所收藏的神明衣飾,他也希望大家能透過拿在手中端詳,更細緻的觀察認識。圖 © 臺灣當代文化實驗場,許?倩攝影

在文化耕耘的務實面向上,庄頭文化公司目前有幾個明確的運作方向,一個是從事文化研調的工作;另一個則是承接政府的補助案或是舉辦走讀導覽、創造實際收益的推廣活動,因此組織內部分設為「傳藝組」和「探險組」。傳藝組的主要工作就是藝文類型,像是調查早年在安坑地區十分流行的軒社文化,就屬於傳藝組的業務範疇,有感於安坑的軒社凋零速度相當快速,傳統藝術的迫切保存必要成為他們責無旁貸的任務之一。

「傳藝組」的設立與吳柏瑋的個人經驗有關,他的阿公以前就參加過地方軒社,並擔任小旦的角色。也因為這段淵源,吳柏瑋採訪到了與他的阿公同年代、曾參與二城興義社的苦旦廖心旺老先生(採訪時年91歲)了解當時的文化與發展脈絡,並且在新店潤濟宮辦理了一次特別的軒社體驗課程。令他備感驚喜的是有興義社會老班成員到場參與分享,讓他們真正在那場活動中體會到地方傳統藝術傳承的重要,在這樣的因緣際會下,團隊定調了「傳藝組」的階段性任務,要朝地方傳統劇發展,並且回歸社區參與,往後,傳藝組也會朝向劇團的籌備,實地上台「搬戲」。

暗坑文化復興計畫「再見軒社.興義風華」活動現場。圖/暗坑文化工作室提供

暗坑文化復興計畫「再見軒社.興義風華」活動現場。圖/暗坑文化工作室提供

至於「探險組」的部分,因為安坑跟新店一帶的文化內容,很多都要細部進行文化踏查,文化工作的採集始於足下,只有真正實地去現場勘查過,才能找尋先民生活過的痕跡。因為這裡的山谷地貌特質,有時候須要實地上山下海,尤其是墓葬的踏查,就像在探險一樣。「我們做墓葬踏查的時候,有一些陵墓的位置你根本看不到路,我們就三、四個人拿著鐮刀去割草。」去年底,他們尋著從未曾開發過的水域生態進行野溪尋跡,在完全沒有路、沒有燈,手機訊號也不通的深山野嶺中發現了或許是泰雅族出草的痕跡。吳柏瑋表示:「以前原住民從番社出發,因為路途遙遠,中間就會有一些供途中休憩的中繼站,因為出草會砍人頭,在中繼站裡也會找到一些祭壇的痕跡。」而這些沒有記載在案的資料,都需要親身去踏查才能找尋的到。

實地考察、親眼見證,這也是「探險組」的重要特性,為了進入這些人跡罕見不易到達的地方,吳柏瑋會幫參與踏查的人員準備工具包;除此之外,團隊也會舉辦室內課程,請來像是臺灣重要的文化資產專家陳仕賢等研究者來為參與者進行講課與訓練。

2021年的「阮兜!暗坑」展覽現場。圖/暗坑文化工作室提供

2021年的「阮兜!暗坑」展覽現場。圖/暗坑文化工作室提供

與「探險組」息息相關的還有「文化培力」的工作。團隊會從文化、語言、實際觀察等多方面向來培訓導覽人員,引導參與者針對地方文史的內容來做深度的介紹。例如2021年的「阮兜!暗坑」展覽,團隊中的三組夥伴負責的區域跟主題都不一樣,就被分別被給予不同的訓練內容。但當中也會有共同培訓的通則,像是田調與訪調的一些「眉角」;比方說發音與地名的正確性、基本的地方文化內容知識,再來就是針對勘查如何從古地名介入,而後實際做墓葬的紀錄,最後配合專業人士或單位――例如說陳仕賢、林柏昇、李時光、還有新店文史館等――從全臺灣的墓葬文化、記錄墓葬文化的人、一些地方經驗,再回到新店本身的文史工作,了解墓葬與家族間的關係,組織成一套完整的脈絡。簡言之,要先做好田調訪問與實地踏查的工作,再去查閱文獻的佐證或回歸耆老的口述歷史紀錄,並提供這套完整的流程成為參與者依循的學習模式。

即使以一個沉潛五年、成立不到兩年的年輕公司來說,庄頭文化公司所運作的項目已然非常豐富,然而吳柏瑋的內心仍舊有想要達成的目標――也就是設立「文化銀行」。他說明道,對於古厝來說,最理想的狀態是能夠現地與現況保存,但面對最終因未具文化身分而面臨被拆除的古厝,他則希望能建立起文化資產銀行的制度,將建築物的概念、工法技術與留存的實體物件蒐集存放起來,用以讓後人能夠藉由這些受到完善保存的有形與無形內容,更加認識傳統工藝,甚至作為復建工法的資料。但文化銀行的運作有賴空間與設備的支持,現階段對於公司能撐起的財務狀況來說是沉重的負荷,這也成了他心底的遺憾與目標。

由上述這些組織分工與工作流程看來,地方文史的爬梳是一份細緻的工作,必須要全面了解相關的知識,比方說光是談到「信仰」就可以談到信仰的藝術、來源、派別等,為了釐清這些,往往需要去蒐集與閱讀大量的一、二手資料:論文文本、殖民時期的文件,乃至於尋問像師公這樣擁有特殊專業的人士,來建構出完整且具可信度的內容。在這當中,口述歷史是十分重要的一環,能幫助了解到隱藏在官方文書底下的故事,也是那些最「在地」的故事。

吳柏瑋曾經聽過耆老談起一則先前未有公開記載的「殺人埔」事件:日本殖民時期,暗坑也有不少的抗日反動勢力,這些反抗勢力被日本政府認為是「土匪」。過去為了抓捕這些匪類,日本官兵前往暗坑的車仔路庄意圖抓捕這批動亂人士,卻在車仔路庄誤抓了七、八十個人,並送到庄頭附近槍決。其實這批人並非土匪,真正的土匪窩藏在當時磺窟的「土匪城」。吳柏瑋訪問到的林姓耆老家族中也有不少人被不幸地誤殺,當時日本官兵行刑的地方,如今仍被老一輩的居民稱為「殺人埔」。

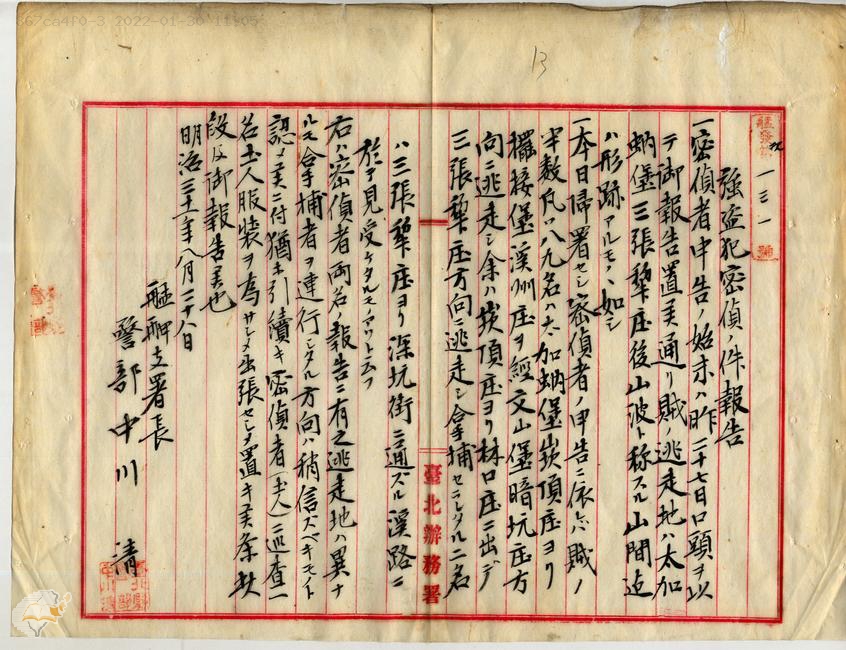

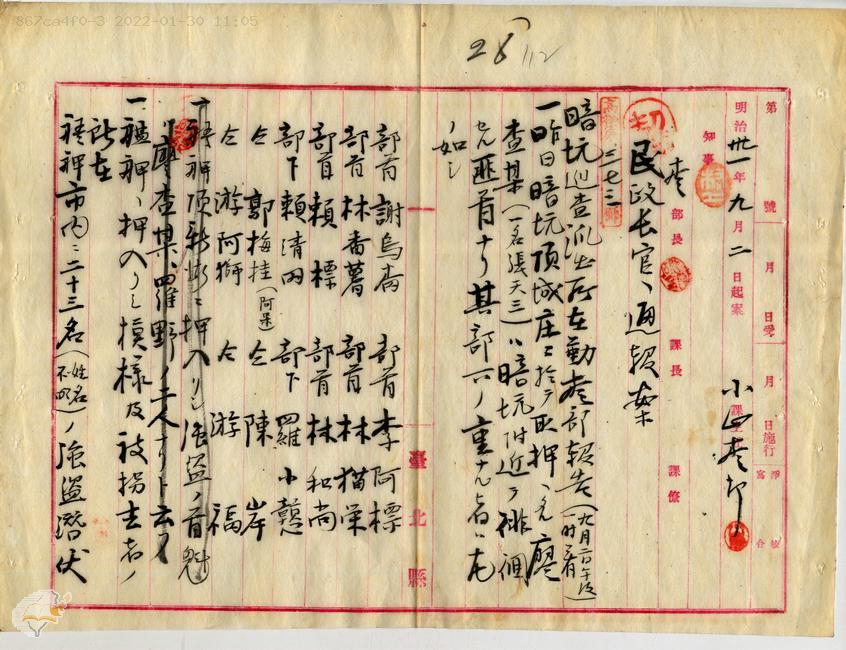

團隊最近也找到一份當時警察局撰寫的報告疑似佐證了這個事件的真實性。報告書中完整地記錄了日本殖民初期,有一群匪人從安坑跑到艋舺去搶劫了一位葉姓的中藥商又逃回來,為了要圍剿這群匪人,日本政府將進兵圍剿匪類的路線都畫了出來;因此這則原本只是耆老口述的鄉野故事,有了記錄在案的真實資料,讓團隊十分振奮。但這份文件究竟是不是「殺人埔」的確切佐證至今仍未有定論,因為知道這些事情的人都不在了,當時訪問的林姓耆老也在訪問的兩個月後高壽離世,這也是吳柏瑋認為從事文化工作中讓他備感焦慮的一點,因為耆老們正在流失,文化也在凋零,做文化就是在向老天爺搶時間。

「艋舺許叶夢被害搜查一件書類(元臺北縣)」(1898-08-01),〈明治三十一年臺灣總督府公文類纂元臺北縣永久保存第三十二卷警察〉,《臺灣總督府檔案.舊縣公文類纂》。圖/國史館臺灣文獻館典藏

「艋舺許叶夢被害搜查一件書類(元臺北縣)」(1898-08-01),〈明治三十一年臺灣總督府公文類纂元臺北縣永久保存第三十二卷警察〉,《臺灣總督府檔案.舊縣公文類纂》。圖/國史館臺灣文獻館典藏

「艋舺許叶夢被害搜查一件書類(元臺北縣)」(1898-08-01),〈明治三十一年臺灣總督府公文類纂元臺北縣永久保存第三十二卷警察〉,《臺灣總督府檔案.舊縣公文類纂》。圖/國史館臺灣文獻館典藏

「艋舺許叶夢被害搜查一件書類(元臺北縣)」(1898-08-01),〈明治三十一年臺灣總督府公文類纂元臺北縣永久保存第三十二卷警察〉,《臺灣總督府檔案.舊縣公文類纂》。圖/國史館臺灣文獻館典藏

文化工作這件事情的關鍵就在於如何讓公民、讓參與者產生興趣,如何讓他們從文化的外部觀看者變成文化內容的一份子。團隊開始介入新店與安坑不義遺址的存廢議題,就是發現存在於此地的不義遺址密度竟然如此之高,顯示出該地作為戰後軍管區的重要歷史,加之這幾年不義遺址也成為一種顯學,於是團隊開始針對地方不義遺址的記憶做採集,並且設計出一套以不義遺址為主軸的文化路徑與文化行動。2021年團隊承接的一項教育計畫便設計了一套遊玩方式,從認識這個地方開始,藉由活動讓生活在自由年代的參與者們了解到自由是多麼地來之不易;這項「白色暗坑――不義之谷」活動,融合了遊戲、導覽、戲劇表演的內容在裡面,經過幾次的演練與實地活動辦理,團隊未來也希望朝著更加沉浸式的體驗來規劃,讓參與者在過程中,認識地方,也更認識自己。

如同吳柏瑋這樣一批文化工作者,將隱藏在歷史微塵之下的這些悲歡、榮辱與生死一一抽絲剝繭,為我們揭示與還原了先民們真實的樣貌,如同他所闡述的:「文化就是生活,我們做的就是把先人的智慧傳承下來,讓後人不要失根。」