Kinmen on the frontlines between Nationalist Taiwan and Communist China after 1949 exhibits a unique historico-political relationship between two regimes. With its vast networks of military installations, the remote island makes a stark first impression upon visitors. Any mention of Kinmen brings to mind its military legacy. With the abolishment of the military administration system in 1992, the austere atmosphere of militarization gave way to tourism, unveiling its mysteries to the outside world.

Before I came to the island, my imagination of Kinmen had been shaped by textbook and popular media depictions, of an island covering 150 square kilometers, located far from Taiwan and just 5 km off the coast of Xiamen. Not only was this the base for Koxinga’s campaign to repel Qing advances and restore the Ming dynasty, but it was also at the forefront of the Nationalist government’s plans to strike back at the mainland following its retreat to Taiwan in 1949. More recently, fortifications once built to repelling military invasions had become a theater of cross-strait exchange, forging a unique battlefront cultural landscape.

Six years ago, work first brought me here on a turbo-prop jet, descending through the clouds across the gui tiao zhai (railroad track fencing)1 piles on the beach, looking at forts and barbed sisal or cacti patches that make up the coastal defense from a bird’s-eye view. Thus began my close encounters with the island.

The battlefield heritage most associated with Kinmen are its impregnable fortifications, wartime stories in the villages, and its impressive underground tunnel system, which are some of the most well-preserved places in the world, spanning decades from the periods of active war to Cold War and truce.

Strolling along this former frontline on the sea, I observed the relics of the Battle of Guningtou, artillery shell marks on the walls of Beishan Old Western-style House, the vast networks of the Qionglin Civil Defense Tunnel, and morale-bolstering slogans on the walls of civilian houses along Sha Mei Old Street and Hou Shui Tou, such as “Defeat Chinese Communists and oppose Soviet Russia,” “Protect secrets and thwart spies,” “Loyalty to the Leader,” “Slaughter ZHU and MAO.” These all mark the Cold War era in which Kinmen witnessed heart-wrenching events through blood and tears.

A civilian housing settlement marked with the slogan “Defeat Chinese Communists and oppose Soviet Russia.” Photo by Yiru GUO

A civilian housing settlement marked with the slogan “Defeat Chinese Communists and oppose Soviet Russia.” Photo by Yiru GUO

Mashan Observation Post featuring the military slogan “Take back the motherland.” Photo by Yiru GUO

Mashan Observation Post featuring the military slogan “Take back the motherland.” Photo by Yiru GUO

A former member of the Kinmen Self-defense Militia once told me, “Words against the Communist Party of China or MAO Zedong such as ‘Slaughter ZHU and MAO’ had been a part of everyday life in Kinmen… times were tough, but it is an honor to fight for our country. The Kinmen spirit is to remain steadfast in the face of hardship, to work hard and have no fear of death.” The Militia’s spirit in Kinmen is not only reflected in the military heritage which endures long after the battle had ended, but also through their verbal accounts of the past, a most tangible form of military cultural memory.

But what surprise me the most about Kinmen, besides its battlefield heritage, are its Southern Min roots and its status as a hometown of overseas Chinese.

Kinmen’s Southern Min roots go deep, further than the well-preserved traditional cluster housing and red brick buildings seen at every turn, such as ancestral shrines and historic houses. It also stretches to the language, lifestyles, religious beliefs, and various aspects of honors, ceremonies, sacrifices, and rituals. The authentic Southern Min accent, puppet theater, nature worshipping in the form of shisa figures and shigandang plaques, and religious beliefs from Matsu to Chenghuangshen (god of the boundary) are all deeply seated in everyday life. Besides preserving the traditional Heluo culture of the Zhongyuan region from whence residents were descended, it also integrates regional conditions and developments, creating an unprecedented and far-reaching cultural history.

Of these qualities, the traditional concept of kinship provides a unique social foundation in Kinmen. Each cluster or settlement consists almost entirely of the same blood relatives who share a common surname, and each village maintains its own ancestral shrine. Besides honoring ancestors, the shrine also serves as a bond among individual members of the clan.

The lavishly decorated HUANG ancestral shrine in Southern Min style, located in the Jinsha Township of Kinmen. Photo by Yiru GUO

The lavishly decorated HUANG ancestral shrine in Southern Min style, located in the Jinsha Township of Kinmen. Photo by Yiru GUO

Visitors to the villages of Kinmen are often struck by the exquisite designs of ancestral shrines and plaques, the order of spaces, and more abstractly, patriarchal ethics. Each ancestral shrine represents a historical snapshot album of a clan. The mass worship ceremonies by members of the clan at each shrine, such as those of the “Qionglin TSAI Lineage Ancestral Worship Rites,” further demonstrate the unbreakable bonds among blood relatives, and are often attended by cultural history researchers. Clan culture is not only the religious heart of local life but also the spiritual pillar of regional development.

Recalling the time when I first arrived in Kinmen, a senior person who shared the same family name, greeting me for the first time in a business setting, inquired “Where is your ancestral home?” At first I thought he meant what place I had come from in Taiwan. But then he added that he was asking about my ancestor’s origins, or if I knew the ancestral hall of my clan. Accordingly, the ancestral hall of the GUO family is “Fenyang” and in the later Ming and early Qing periods, a branch of the GUO family emigrated to Taiwan from Fujian and settled in the vicinity of Changhua and Kaohsiung. Since I came from the Luzhu District in Kaohsiung, it can be surmised that our ancestors had descended from the same branch, and therefore we should look after each other. After that, I received a lot of help from the person at work and learned much about the local tradition from him. It not only gave me a sense of the warm and caring aspects of the Kinmen people, but also launched me on a journey to explore my roots, deeply experiencing this ceaseless cultural connection across the generations, and how it had shaped a stable social identity and constructed a deep concern through history.

Village elders at the HUANG family shrine during the Winter Solstice Ancestral Remembrance Ceremony. Photo by Yiru GUO

Village elders at the HUANG family shrine during the Winter Solstice Ancestral Remembrance Ceremony. Photo by Yiru GUO

Village elders at the HUANG family shrine during the Winter Solstice Ancestral Remembrance Ceremony. Photo by Yiru GUO

Village elders at the HUANG family shrine during the Winter Solstice Ancestral Remembrance Ceremony. Photo by Yiru GUO

As times progress and as cultures come together to engage in dialogue, Kinmen as a society has become more diverse.

To seek new opportunities abroad for keeping their heads above water or escaping from wars, many Kinmen men leave for places like Malaysia, Singapore, or Indonesia to find work, in what was known historically as luò fān or chu yang. Once they have found success, thoughts towards family were substantiated with “overseas transfer” of funds home, or by erecting new residences back home in the style of the places they visited (often in Southeast Asia). Of these architectures, the foreign-style houses, known in the vernacular as huan-á houses, were most notable with their eclectic combination of western and eastern elements.

One of the most famous western-style residences of Kinmen, the CHEN Jing-Lan Western House, was built by Singaporean overseas Chinese CHEN Jing-Lan in 1921. Its façade painted in pure white, finely sculpted relief, and symmetrical arches differ from traditional Min-style red brick constructions and is considered a masterpiece among huan-á houses. Also seen in numerous settlements are western-style school buildings erected by returned overseas Chinese, such as Rui You School in Bishan Village. It features a façade in Baroque style, with Indian police and musical band figures on the pediment and floral and crane motifs as plaster relief ornaments in a mix of eastern and western styles. These western-style buildings with different programs are a testament to the achievements of returned overseas Chinese in Kinmen, as well as their influence on their hometown and cross-pollination of ideas between Southern Min and Southeast Asian cultures. Their journeys in the 20th century between Kinmen and places abroad not only enriched the architectural styles of Kinmen but also established a vibrant returned overseas Chinese culture.

One of the most famous western-style residences of Kinmen, the CHEN Jing-Lan Western House. Photo by Yiru GUO

One of the most famous western-style residences of Kinmen, the CHEN Jing-Lan Western House. Photo by Yiru GUO

Engrossing stories abound with overseas Chinese returning home in riches, as well as those who have lost all fortune, realizing it was all a pipe dream. Some also set out with no jealousy or greed, not expecting what they’ll find. The residents all speak of having three or four out of five relatives in their respective families travel to the South China Sea region to find new fortunes. A coworker living in Qingyu, Shu-Lan, also shared her grandmother’s story of her grandfather leaving the family behind for the South Sea when she was three months pregnant, leaving her to shoulder the burden of raising the extended family alone. Shu-Lan recalls her mother’s story of being brought along by Shu-Lan’s grandmother to Haiyin Temple on Taiwu Mountain, to pray for the safety of her family and her grandfather’s fortune abroad. Shu-Lan’s grandmother would point at the Eighteen Arhats and say to Shu-Lan’s mother, “when you have counted all 18 of the Arhats, your father would be back.” Decades later, Shu-Lan’s grandfather still hasn’t returned, and Shu-Lan’s grandmother spent all her life in Kinmen looking after the family without complaint. This not only speaks for the resolve of Kinmen’s women under dire circumstances, but also evokes the bitter fate of overseas Chinese in which “ten leave, six die, three stay, and one returns.” Yet it also shows the resilience of the island, constituting an emotionally rich island memory and vitality.

Traditional Southern Min red brick architecture contrasts with the foreign-style buildings with complementary eastern and western features. Photo by Yiru GUO

Traditional Southern Min red brick architecture contrasts with the foreign-style buildings with complementary eastern and western features. Photo by Yiru GUO

Looking at Kinmen’s everyday sights of the battlefield, Southern Min, and overseas Chinese cultures, and listening to the touching stories behind them, one feels the importance of museums in the preservation and presentation of histories and communal life.

Besides the various architectures and rituals within the original cultural contexts and environmental settings, cultural relics in the museum also serve local culture and shared memories through various guises, embodying social experiences and mental journeys and allowing them to be seen and be touched:

1. Objects imbued with memories or created directly for the memories of the individual and/or community: Productions directly related to ritual and custom, for an individual, an event, or locus. Also of objects collected and preserved in relation to the personal or collective memory, such as heirlooms and war memorial plaques.

2. Objects for invoking memories: Able to encourage viewers to recollect their personal experiences of life, evoking and actively sharing memories related to past events, usually cultural relics with a specific year attached, such as old photographs that remind viewers of their childhood.

3. Objects reflecting or representing the tangible cultural assets of a society: An item that serves as a token of a society’s tangible heritage, facilitating an understanding of the society that had produced and utilized it, prescribing as well as discerning memories related to social practices, attitudes, and beliefs, such as stone carvings, ancient tombs, and cave paintings.

4. Objects conveying intangible cultural heritage: Many cultures pass down their cultural memory across the generations through intangible cultural heritage, such as performing arts traditions, traditional arts and crafts (skills), and folk customs. The objects produced or utilized serve as a medium for intangible craftsmanship, inheritance, and guided practice, so that the memories of the producer, user, and inheritor live on through the object, such as the Ong Chun (royal ship) in the Ong Chun Ceremony.

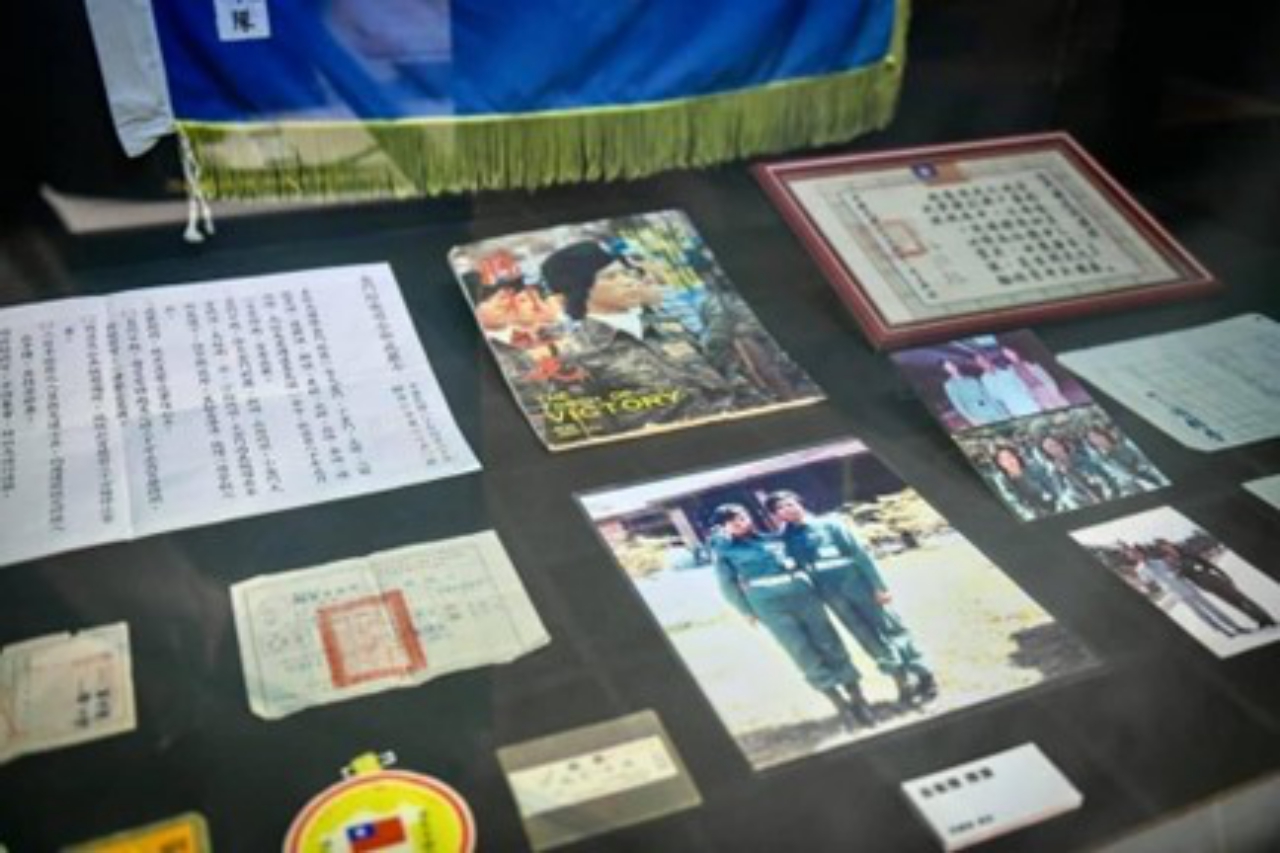

Artifacts of the Self-defense Militia on display at the Kinmen Museum of History and Folklore. Photo courtesy of Kinmen Museum of History and Folklore

Artifacts of the Self-defense Militia on display at the Kinmen Museum of History and Folklore. Photo courtesy of Kinmen Museum of History and Folklore

Museums as cultural, historical, and memory repositories encourage exchange between artifacts and audiences, and through the process of collection, archival, and the display of items of cultural significance, they record the histories to become the preserver and protector of local memories. In particular, the cultural relics in regional museums are often inextricably linked with the local community. For example, the first offshore significant antiquity Portrait of CAI Fu-Yi, exhibited by Kinmen Museum of History and Folklore, is a family heirloom of the CAI family of Caicuo Village in Kinmen. CAI Fu-Yi is the 21st ancestor in the genealogy of the CAI family in Caicuo, and is also a well-known figure in the political and literary circles in the Wanli and Tianqi eras during the last years of the Ming dynasty. He is widely associated with the origins of the Kinmen culinary specialty the shì bǐng. Every year at winter solstice and the anniversary of CAI Fu-Yi’s death, the CAI family unfurls his portrait and displays it as part of their ritual. The portrait is a visible form of collective memory, and an indispensable part of Kinmen’s Southern Min culture. Another example is the exhibition Civil Defense: Defender of Wudao. On display are items used by the Kinmen Self-defense Militia and the Elite Patriotic Guard, such as National Day military parade uniforms, the original martial law ordinance document, the Elite Patriotic Guard insignia and letter of commission, all serve as testaments to Kinmen’s military culture, memory nodes dotting the life stories of soldiers and civilians.

Museums serve to collect and develop tangible and intangible cultural heritage, and in recent years, Taiwan’s museums and cultural heritage preservation practices have steered towards cross-disciplinary collaboration, aligned with international trends and practices, Kinmen being no exception. As a member of the cultural heritage preservation community, the museum extends beyond its traditional frameworks of displaying and maintaining internal collections, gradually expanding to protect local cultural heritage outside the museum, including the gathering of any relevant historic artifacts and oral histories.

The imprints left on this island represent the values of ordinary residents fighting for survival between periods of war and peace, living by their traditional culture and pursuing peace, shaping a multi-dimensional cultural landscape. It involves not only the military battlefield heritage for which it is widely-known, but also the overlapped Southern Min and returned overseas Chinese cultural memories spanning in time and space, which in due time ages beautifully like a vat of local Kaoliang liquor.