劉冠麟在螢幕另一頭侃侃而談,那是週日的早晨,倫敦的炙熱好不容易和緩了點,目前於帝國理工醫學院(Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine)化學工程所(Department of Chemical Engineering)就讀的劉冠麟,娓娓道來自己乍看百轉糾結的求學經歷,到如何用最新技術鑑定與分析,協助文物資產保存更進一步的發展。

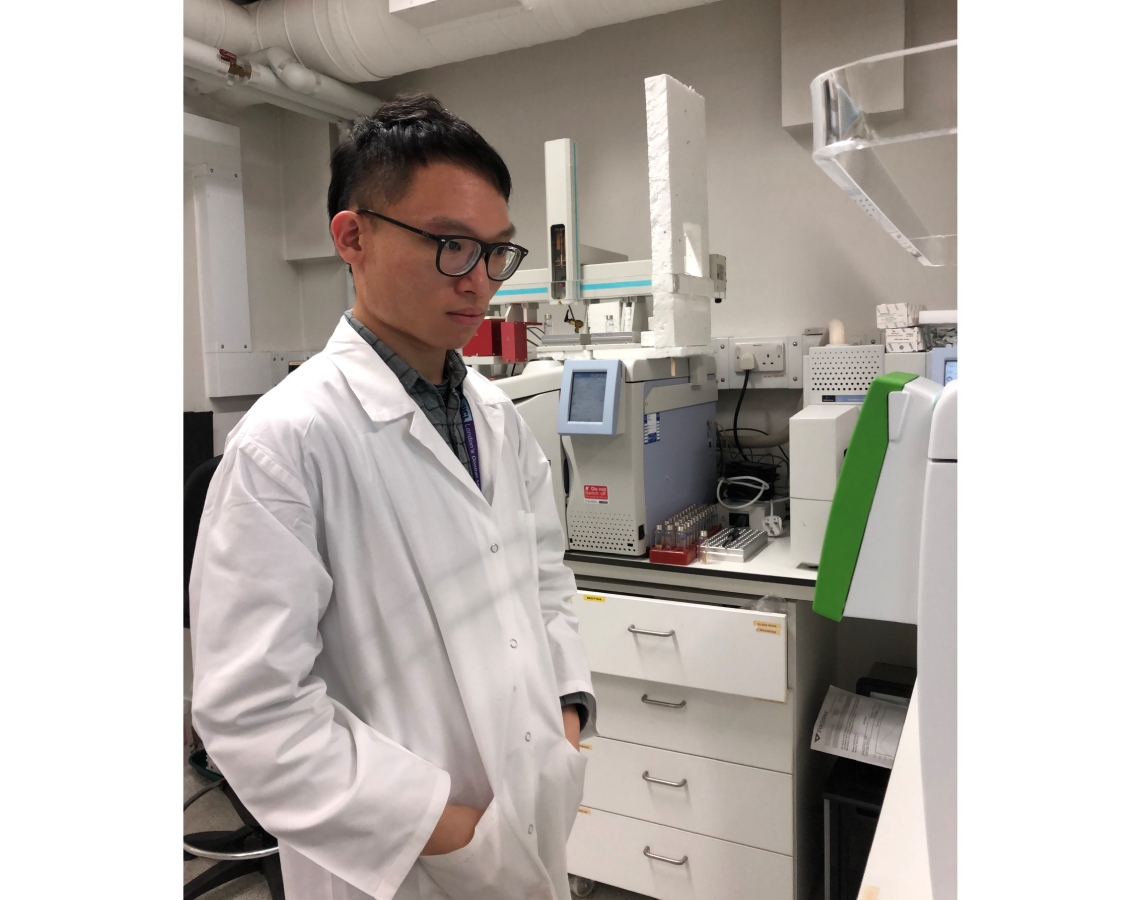

畢業於國立清華大學材料科學工程學系的劉冠麟,轉進至文物保存與修復研究之路。圖/劉冠麟提供

畢業於國立清華大學材料科學工程學系的劉冠麟,轉進至文物保存與修復研究之路。圖/劉冠麟提供

熟悉的人都喚劉冠麟「小路」,畢業於國立清華大學材料科學工程學系的他,自求學階段就是學校裡的怪咖學長,莫名跑來中文系和我們挨著邊搖頭晃腦解析古典詩詞,同時又在號稱「台積電保證班」的材料系學得有聲有色,甚至日後研究所還一頭栽進相對冷門的仿生材料研究。畢業後沒多久,卻又看到他一邊在桃園核能研究所工作,一邊赴國立中央大學藝術學研究所旁聽故宮登錄保存處陳東和副研究員課程的筆記。甚至不出數年,劉冠麟便申請至倫敦大學學院(University College London)永續遺產學院(Institute of Sustainable Heritage)的「藝術、遺產與考古中的科學與工程」(Science and Engineering in Arts, Heritage and Archaeology,簡稱SEAHA)學程就讀,然而轉眼他又投入化工研究,在封城期間每天照常進學校翻弄實驗室高價的儀器,從油畫和攝影等媒材的藝術品取樣分析,甚至刻意操作媒材的衰敗(degradation)來展開他的修復研究。

等等,操作衰敗聽起來格外不妙。

劉冠麟解釋,許多人都認為修復就是實際動手修復作品,但其實修復涵蓋面向極廣且具備繁複過程。而如今的「科技保存」,便是希望透過科學儀器的鑑定,來了解作品的原始樣貌為何、修復該如何著手、使用何種材料才能貼合作品原貌。

一開始懷著要全心投入文化資產保存的劉冠麟來到SEAHA,期待能藉由課程累積文獻回顧、田野調查與文化保存概論等多重面向的課程來奠定知識涵養,進而更進入考古學院博士班。然而,一場田野改變了他的想法,讓他轉而走上化工博士的道路。

那場為期兩週的田野調查發生在赫里福德郡(Herefordshire)中Hellens Manor古宅,古宅可追溯至12世紀,如今幾經易手但仍有著驚人的文物收藏。SEAHA的碩士生正是受莊園邀請前往調查,紛紛投入環境、建築等項目的研究,而劉冠麟則是拿著他被分發到的多光譜成像儀(Multispectral Imaging,MSI)和高光譜成像儀(Hyperspectral Imaging,HSI)著手展開古宅內的油畫分析與驗證。

Hellens Manor大宅中正巧有一幅充滿爭議的《萊斯肖像》(The Rice Portrait),據傳為英國文學家珍.奧斯丁(Jane AUSTEN)1 年少時由畫家奧茲亞.漢弗瑞(Ozias HUMPHRY)所繪製,不過許多專家學者皆從年代與服裝風格分析等多番角度提出質疑 2,而劉冠麟的工作便是希望能夠操持X光探測畫作的金屬成份,給予科學方面的專業見解。

在多光譜成像儀(Multispectral Imaging)檢測下的《萊斯肖像》(The Rice Portrait)。圖/劉冠麟提供

在多光譜成像儀(Multispectral Imaging)檢測下的《萊斯肖像》(The Rice Portrait)。圖/劉冠麟提供

透過不同波長的光探測,發現畫作上同時兼具鋅元素和鈦元素,劉冠麟懷疑畫作有可能運用1920年後才出現的鈦白顏料,這也致使畫作完成年代從原先預估的1788年大幅往後移動,不過莊園主人也強調《萊斯肖像》曾遭遇過火災,鈦白顏料極有機會是後續修復過程中所添加。因此劉冠麟迫切希望能夠進一步運用微侵入式(micro invasive)研究,取樣觀察畫作的橫截面,以此分析顏料的使用方式與分佈位置完成鑑定,當時礙於手上現有技術限制無法完成,也促使他開始思考在科學技術上打磨修煉的可行性。

偶然機會下,劉冠麟看見帝國理工學院的座談會「文化遺產的科學與工程研究」(Science and Engineering Research for Cultural Heritage),該座談會集結科學背景殊異但積極跨領域的研究者定期交流,藉此促進社群蓬勃發展。當時他被教授謝爾蓋.卡扎里安(Sergei G. KAZARIAN)藉由光譜儀深入藝術研究的講座吸引,主動去信聯繫,也促成日後研究方向大轉彎,又再度走向化工所的道路。

進入博士班後劉冠麟被教授指派使用傅立葉轉換遠紅外光光譜儀(Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy)進行藝術品分析,事實上,過去他的碩士論文便曾由此著手。當時維多利亞與艾伯特博物館(Victoria and Albert Museum,V&A)給予劉冠麟其收藏的羅賓漢花園社區 3 水泥柱,他操持高光譜成像儀,藉由近紅外線(Near infrared,NIR)非侵入式(non-invasive)偵測建築樑柱表面,確定其水泥衰敗(concrete weathering)4 狀況後,再進一步取樣分析。

目前,劉冠麟的研究工具以傅立葉紅外光譜儀(ATR-FTIR spectroscopy and spectroscopic imaging,簡稱ATR-FTIR)為主,透過非毀壞式(non-destructive)的程序,以肉眼難以辨識的微侵入深入研究對象,取得樣本封存於樹脂中,樣本得以重複使用,在文化保存與科學研究中達到平衡。而ATR-FTIR 的優勢,便是能夠偵測化學物質的鍵結結構,進而判斷物件本身的組成,目前ATR-FTIR 已被運用在玻璃、紙張、陶器、攝影等媒材,其中又以油畫為最大宗。5

劉冠麟與英國國會皇家畫廊(the Royal Gallery)所合作的油畫衰變研究即為最好的例子。英國國會雖然為大不列顛國協最高立法機構,但在橫跨數世紀仍舊收藏超過8,000件藝術品,涵蓋繪畫、雕刻、壁畫和織品等,而在中央大廳四角的聖人馬賽克(Central Lobby Saint Mosaics)亦為收藏一大特色 6,然而其原稿的油畫在近年卻發現有泛白的痕跡;經過取樣分析,劉冠麟發現過去藝術家頻繁用來打底的鉛白( (PbCO3)2·Pb(OH)2)以及顏料中蘊含的鉛,容易隨著時間與油畫調和用的油脂產生皂化反應而逐漸移動到表層,當跑到表層的鉛與空氣中的硫化物碰撞產生反應後,進而變為白色的硫酸鉛(PbSO4)出現在畫作之上。劉冠麟統稱這些硫化鉛為衰敗後的產物(degradation products),也指出這現象頻繁發生在許多歷史悠久的藝術品之中。

劉冠麟坦言,一開始經儀器發現硫化鉛時,他也無法肯定此為外來物或是畫家本身所運用的顏料,即便詢問館方人員也無法得到解答,只好自己一頭埋身於藝術史裡苦苦研究方才找到一條明路。對他來說,這彷彿是另一種在油畫上的科學考古,藉由研究油畫的層理,輔以科學儀器和歷史知識,絲絲挖掘方才得到定論。此研究論文也預計在年底正式對外發表。

劉冠麟向帝國理工學院檔案庫(the Imperial College archives)借調蛋清照片進行鑑定,亦透過科學分析,確認文物的實際狀況。圖/劉冠麟提供

劉冠麟向帝國理工學院檔案庫(the Imperial College archives)借調蛋清照片進行鑑定,亦透過科學分析,確認文物的實際狀況。圖/劉冠麟提供

而為了研究衰敗,劉冠麟也從eBay拍賣網站上蒐羅19至20世紀初的黑白相片,利用烤箱和化學藥劑破壞相片,藉此理解攝影作品破壞的多重路徑,進而回頭檢視修復的可能。有趣的是,透過儀器掃描,他也意外發現賣家標注的蛋白相紙(albumen print)應為明膠銀鹽相紙(silver gelatin print)7,這也引起他的興趣。劉冠麟表示,雖然部分鑑定師和考古學家能仰賴肉眼鑑定相片種類,但他還是希望能夠以科學儀器形塑另一種判別方法,而當他進一步與帝國理工學院檔案庫(the Imperial College archives)借調蛋白照片鑑定時,卻意外發現這批照片上面並沒有任何蛋白質成分,應為鹽印法(salt print)製作的相紙。更讓他深信經過科學的分析,有機會更近一步理解文物的真身。

不過研究同時,劉冠麟也不時需要以文物保存的角度,與其餘純理工背景的實驗室同仁提出他的專業判斷。日前實驗室首腦卡扎里安教授由亞美尼亞當地博物館取得該國重要畫家馬爾季羅斯.薩良(Martiros SARYAN)8 三件作品《史塔夫林的早晨》(Morning in Stavrin,1909)、《阿拉伯舞者》(Arabian dancer, 1913)、《基洛瓦坎教堂》(Kirovakan Church,1948)的樣本,讓劉冠麟大為震驚的是,當地博物館竟然直接以刮勺將顏料從油畫表層刮下,裝在塑膠夾鏈袋中提供給實驗室,這舉動不僅違反一般試品製備(sampling)流程,甚至也對藝術品本身造成不可逆的傷害。劉冠麟藉機提醒教授該如何協助當地博物館以較為文物友善的方式進行樣品取樣,如今教授也努力推動英國的國家畫廊(the National Gallery)將其已然老舊淘汰但堪用的儀器捐贈到亞美尼亞。他不禁感嘆在文物保存這一條路上,各國仍舊有殊異的道路要走。

-.png) 實驗室取得亞美尼亞重要的畫家馬爾季羅斯.薩良(Martiros SARYAN)的作品,並針對三件作品進行修復分析。圖/劉冠麟提供

實驗室取得亞美尼亞重要的畫家馬爾季羅斯.薩良(Martiros SARYAN)的作品,並針對三件作品進行修復分析。圖/劉冠麟提供

訪談最後詢問到關於未來打算,劉冠麟打趣說著畢業後如果混不下去就要去台積電工作。我們兜兜繞繞閒聊他念文物保存的同學許多都進了金融圈。然而,核心問題仍舊是博物館人才薪水的低廉,無論在臺灣或是英國都是如此。另一方面,即便有豐沛的學養,博物館的科學研究人員仍然被視為展覽與收藏下的附屬品,不僅薪水相對微薄,對於收藏品的研究也必須仰賴館內展覽需求,甚至無法展開自己的研究。對即將邁入博士班最後一年的劉冠麟來說,在離開快樂的學術生涯後,要如何拿捏現實與理想仍舊是一大考驗,如何懷抱熱忱繼續前行也充滿徬徨。