如果「Re」意味著一種態度,那麼它能為當前的創作展演提供何種歷史閱讀的特殊視角?這是進入本文正題之前,我們首先必須釐清的。儘管「Re: Play操/演現場」(簡稱「操/演現場」)使用較為寬泛彈性、意義未定的「Re: Play」來涵蓋展覽裡的多種創作取徑,但整體而言,其策展實踐的具體內涵遠遠不是「replay」(重播),更不是對歷史的無差別復返。倘若如此,究竟是基於何種理據,歷史的第二回探訪有其深意?又是什麼樣的機緣,使得我們不再或不願將第一回的原初顯現視為單純的偶然?

「Re」在英文中有多樣的變化,可對應的中文當然也不遑多讓。問題是,在當代藝術的評論脈絡中,我們究竟是使用哪些詞語概念來與它們對接的?舉例來說,「remake」(重製)與「remaster」(復刻)都具有將舊作重頭製作、翻新之意,使作品能符合當前的媒介環境,克服相關器材與載體被淘汰的不利條件。而後者,更往往指運用新的技術,將往日經典之作加以更新,好提升其欣賞面(如音質、畫質)的體驗,因而帶有明確的懷舊意味。在上述兩種概念中的「Re」,「還原/恢復」的意義多半大於「更新/創新」。除了讓當代觀眾更容易接受過去在有限條件之下所產生的經典作品之外,「Re」並不必然指向全新的創作思考方向。毋寧說,「remake」與「remaster」的著眼點至多只是傳統的重新編排(re-arrangement)或重新構造(re-configuration)。又或者,創作者對傳統的承繼,主要是針對既有風格、技法,以及關鍵的文化符碼,找出某種再媒介化(remediation)的有效途徑1。因此,這是藉助新的媒介技術,一口氣掃除往日缺漏與遺憾的「重鑄」(reforge)。

但在藝術領域的討論中,上述的「Re」仍是不夠充分的。特別是當我們聚焦在各種時基藝術(time-based art),如實驗性的錄像、行為表演,乃至於劇場和舞蹈作品的歷史性回顧,「Re」既不能是毫無方向性的「重塑」(re-fashioning),也不該是保守的舊瓶裝新酒。因為我們總是在意新一輪的復返,能否提出關於創作歷史的全新批評視野?同時也關心某一藝術事件於當代的重啟,如何能引領我們通往未來?正因如此,自1990年代起,在描述當代藝術這種「藉由重返過去,以通達未來」的欲望時,「重現」(re-enactment)逐漸成為更常被提及的概念2。 因為它不僅關乎如何取回/恢復(recover)檔案文件,也涉及如何將過去「寫入」當前的創作或策展實踐3。典型者,如2005年於鹿特丹舉辦的「Life, Once More: Forms of Reenactment in Contemporary Art」(斯芬.呂提肯〔Sven LÜTTICKEN〕策劃),或者瑪莉娜.阿布拉莫維奇(Marina ABRAMOVIĆ)在紐約古根漢美術館發表的「Seven Easy Pieces」,重做包括布魯斯.諾曼(Bruce NAUMAN)、維托.阿孔奇(Vito ACCONCI)、約瑟夫.波伊斯(Joseph BEUYS)的經典作品,這類著名的展演案例在在顯示,「重現」已成為許多藝術家、策展人和研究者向藝術史提取力量的重要策略,以及積極理論化的主要對象。

當然,這也表示晚近這波「重現」熱,與理論家佩姬.菲蘭(Peggy PHELAN)4曾經標舉的行為表演本體論立場,是背道而馳的:

倘若行為表演僅能根植於絕對的現場性(liveness),既不可復返,亦不能再現,那麼任何再生產(reproduction)的意圖都會削弱作品本身。儘管這種拒絕一切儲存形式、高度擴張事件當下的基進態度,能賦予行為表演鮮明的抵抗特質。但此一界定的過於嚴格,恐怕也會將「重現」策略所能帶來的優點――譬如行為藝術史內在力量的活化――都加以排除。

確實,著重身體靈光和不可復返性的行為展演,其唯一產出就只有它自身。作品因為清楚指向藝術家自身的純粹消耗,從而確保事件的強度。但這不代表「重現」策略只會是對原作的背叛。因為在此,無差別的同一性(identity)從來都不是它的最高指導原則。相反地,「重現」總是伴隨著必要的詮釋觀點,戮力為原作構築它在當代得以棲身的全新場址(site)。這裡孕育的新「現場」既不能用菲蘭的狹義界定來理解,也不能用基本教義式的「在場」(presence)來框限。毋寧說,它總是交會著新與舊的閱讀視角,是各種檔案意識和檔案力所布置、貫穿的一種複聲化「現場」。

陳武康,《九〇年代的四個劇場性事件》,講座展演,2020。圖/陳浡濬攝影,臺灣當代文化實驗場提供

陳武康,《九〇年代的四個劇場性事件》,講座展演,2020。圖/陳浡濬攝影,臺灣當代文化實驗場提供

據此,「重現」作為創作和策展實踐,必定挾帶兩種層面的反省:其一,誰可以接觸藝術史的檔案?誰有權調閱、抽取、活化這些檔案?其二,重現者如何恢復檔案的可及性(accessibility),而非獨佔?如何在過程中,克服詮釋權與代言權的問題?若就此次「操/演現場」的策展問題意識而言,回應上述問題最直接的答案或許是:因為「重現」策略足以激起一種感性經驗的重新體現(re-embodiment)契機。這是將藝術家的身體視為展演事件、形象身影、方法技巧,乃至於最幽微的情動力(affect)的主要載體,並在全新的時空條件下,賦予過往歷史一個可感的形式和場域。或更確切地說,這是讓身體成為藝術史力量的過道、觸媒,以及「化身」(avatar)。如陳武康的《九〇年代的四個劇場性事件》便可從此角度來理解。這件作品既是1990年代四種身體的歷史縮影上了陳武康的身,同時也是藝術家主動以其言說行動為媒介,激發若不是經此「重現」的敘說演示,當代觀眾的感知便無從匯聚、對焦的一種「反省的場」5。

換言之,「重現」要能體現批判的力道,絕不是複頌已成定局的官方歷史版本,或者為無庸置疑的藝術史經典錦上添花;相反地,它必須跨越歷史研究的純粹耽溺,指出那些值得正名、翻案,或者重新復甦的失落檔案。也就是說,如果不關注屬於未完成者、易逝者、被忽略者的藝術實踐,那麼「Re」就只具有薄弱而扁平的「再次肯認」(re-affirm)之意。因為替歷史的紀念碑添磚加瓦,其價值恐怕是有限的。就此而言,「重現」是一種面向過去,卻不執戀於過去的行動;它凝視歷史,卻不斷扣問著未來。它將我們的興趣和注意力再次導向藝術充滿流變、動態,以及非物質性(immaterial)的一面,但目的不是為了固著化、標本化這些力量,或藉由可反覆操演的「節目/編碼」(program)邏輯,將往日的重要片段降格為空洞的擬像。

林人中的《如果具体派宣言是一首舞譜》也應作如是觀。這件作品的關鍵不在於肯認具體派曾經揭示的藝術實驗多麼不可抹滅,這會是一大誤解;重點當然也不是原本驚世駭俗的足繪、噴壺、自行車胎印究竟怎麼轉化成動作指令,使得原本用於打破繪畫疆界的批判性嘗試,如今也能成為舞蹈實踐的擴延性力量。簡言之,理解具體派的當代演繹,如果只將焦點放在其「擴延」,而不將與之相對應的建置化之力(institutionalization)一併考量進去,便有可能誤解「重現」真正能帶來的創作研究契機。因為這種從媒材到身體、從物件到事件的實驗探索,本身也已被內化成傳統。臺灣的學院體系固然有一套截然不同於具體派和黑山學院(Black Mountain College)的發展路徑,但從媒材特定性之追求,到複合媒材與跨域論爭的思想軌跡依然是有的。如今,該怎麼批判性地指出這個體系的空缺之處呢?

據此,我們不能誤以為1950-60年代的前衛精神,能以相同的姿態和手法再臨。因為臺灣當代藝術的問題意識與挑戰已不同於具體派的時空環境,也有別於自己的1960年代(譬如黃華成與大台北畫派)。換言之,具體派的曾經「擴延」不會因為切換至劇場或舞蹈的創作研究視角,就自動恢復其新意。這是因為「擴延」的概念依然假定領域跟領域之間的隱性疆界;以此為前提的創作實踐,往往一方面期待擴延場域(expanded field)6足以打開一個問題化的空間。但另一方面,卻又弔詭地鞏固疆界自身,從而自我解消身體行動所蘊含的橫越(transverse)動勢。就此而言,林人中向我們展示的與其說是從繪畫到行動、從平面到立體的身體轉譯,不如說是一種參照脈絡的挪移和調校。關鍵是我們可否藉此反思1980年代以降,已然僵固的臺灣學院現代主義的思想框架,繼而構造一個可以相互觀看的亞洲戰後身體實踐的探索歷史?

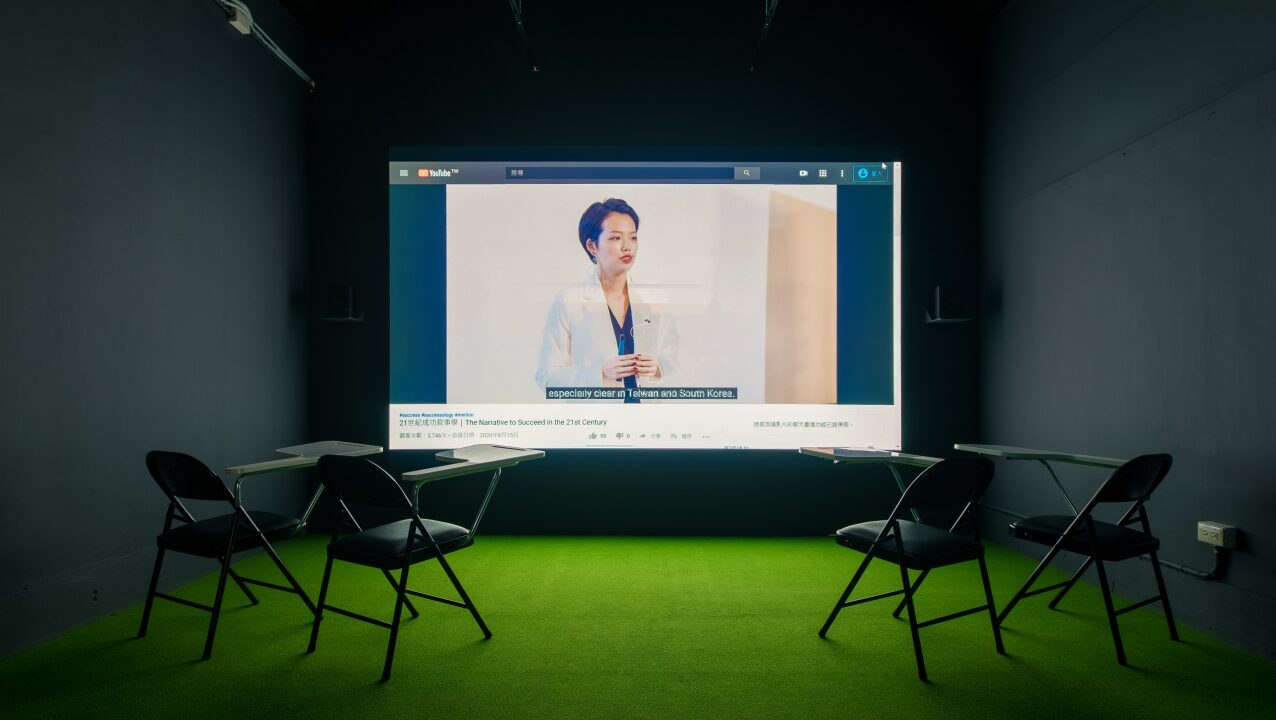

張紋瑄的《魚尾獅是何時絕種的?――21世紀成功敘事學》的研究視野,顯然能與林人中相互對照。只是她更關注從現實與擬仿之間的微妙縫隙,打開社會集體價值觀的批判缺口。在此,藝術家具體演示一個與現實極其相似,實則只是無限迫近的「間距」;無論是購買廣告,還是將演講紀錄上傳至YouTube,都只是對坊間「成功學」講師的典型姿態的刻意挪用。真正關鍵在於藝術家如何召喚隱藏於背後的國家敘事幽靈,讓自己的身體成為其詭異的「神話學建置體系」的欲望載體,甚至讓表演本身就是這種欲望生產之形象/圖像的匯聚點(locus)7。某方面而言,張紋瑄也採取了身體作為化身的策略。她不僅讓亞洲四小龍的虛幻幽靈「現身」說法,同時也在那看似光鮮亮麗的科層語言網絡中,巧妙地構造出一具看似正經(實則空洞無比)的身體。但正是表演最為激情逼真的一瞬間,藝術家讓我們瞥見這種成功學的破裂時刻。

張紋瑄,《魚尾獅是何時絕種的?――21世紀成功敘事學》,講座展演、錄像裝置、文件,2019-2020。圖/陳浡濬攝影,臺灣當代文化實驗場提供

張紋瑄,《魚尾獅是何時絕種的?――21世紀成功敘事學》,講座展演、錄像裝置、文件,2019-2020。圖/陳浡濬攝影,臺灣當代文化實驗場提供

毫無疑問,身體足以成為靈活調動敘事和形象的有力場址。也正因如此,身體應該被我們視為一個可蘊藏各式動作與行動、姿態和氣質的圖集(atlas)。換言之,身體足以回應豐富的「檔案意志」(will to archive)8,但其真正潛能從來都不是為了將自身定影成某個單義化的形象。這點是我們在閱讀高俊宏的《回製(原「山喬菌宏如何複製我的藝術」計畫,2002)》時必須小心留意的。藝術家在1990年代末將自己拋甩於渺無人煙之地的一系列行動探索,並不是為了開發某種行為藝術路線的確切「分支」,或建立某個穩固的反文化戰鬥位置。毋寧說,影像中充滿自我詰問意味的孤絕身影,是一連串與學院建置拉開距離的否定性行動,是各種被藝術家劃上一槓的「主體」,以及複數形式的「我」與「非我」的相互辯證。儘管展場裡的物件充滿些許悼亡的氣質,彷彿這是藝術家亟欲告別的「前現代」時期。然而,恰恰是這些難以標定的「我不是…」或「我不在…」的否定語式,指向了創作生命的真正流變;看似抹除的主體空缺之位,反倒預示終將復返的「我是…」或「我在…」,為高俊宏開啟日後宛如多面晶體一般的「創作–行動–書寫」體系。

高俊宏的《回製(原「山喬菌宏如何複製我的藝術」計畫,2002)》展出現場。圖/陳浡濬攝影,臺灣當代文化實驗場提供

高俊宏的《回製(原「山喬菌宏如何複製我的藝術」計畫,2002)》展出現場。圖/陳浡濬攝影,臺灣當代文化實驗場提供

高俊宏的《回製(原「山喬菌宏如何複製我的藝術」計畫,2002)》展出現場。圖/陳浡濬攝影,臺灣當代文化實驗場提供

高俊宏的《回製(原「山喬菌宏如何複製我的藝術」計畫,2002)》展出現場。圖/陳浡濬攝影,臺灣當代文化實驗場提供

如果藝術家的在場必須問題化,那麼觀眾呢?觀眾在「操/演現場」裡的預設位置是什麼?李銘宸的《解體素描》顯然是為了回應此一問題的探索之作。他一方面關注表演者如何與空總的場域發生對話。另一方面也帶領觀眾在園區內遊走,一同挖掘空間所蘊含的種種特殊質地,思考它們如何成為驅動身體的潛在條件。在此,李銘宸的設想是為其觀眾創造一種對表演環境周遭的感知交纏,無論表演者移動到何處,都能讓演出的當下觸發劇場性的凝視。不過整體而言,《解體素描》提供的主要是旁觀式的參與。這點何采柔與黃思農的《換景》也是類似的。兩件作品的參與觀眾雖然會圍聚,卻也可能相當疏離。這是因為表演者所依循的「指令」仍缺少一種觸覺性專注(tactile attentiveness)的條件,使觀眾的身體無法跟著捲入其中。這意味著,表演事件本身不僅需要具備包覆性,還必須有著如米克.巴爾(Mieke BAL)所說的「黏稠性」(stickyness)9,能夠隨著時間的推移和綿延,不斷纏祟、黏附它們的觀察者。唯有如此,作品才可能提供一個表演者與觀察者同在的共振平面,繼而為每一個看似平凡的日常空間,帶來解體與再構築的感知維度。

李銘宸的《解體素描》演出現場。圖/陳浡濬攝影,臺灣當代文化實驗場提供

李銘宸的《解體素描》演出現場。圖/陳浡濬攝影,臺灣當代文化實驗場提供

何采柔和黃思農的《換景》演出現場。圖/陳浡濬攝影,臺灣當代文化實驗場提供

何采柔和黃思農的《換景》演出現場。圖/陳浡濬攝影,臺灣當代文化實驗場提供

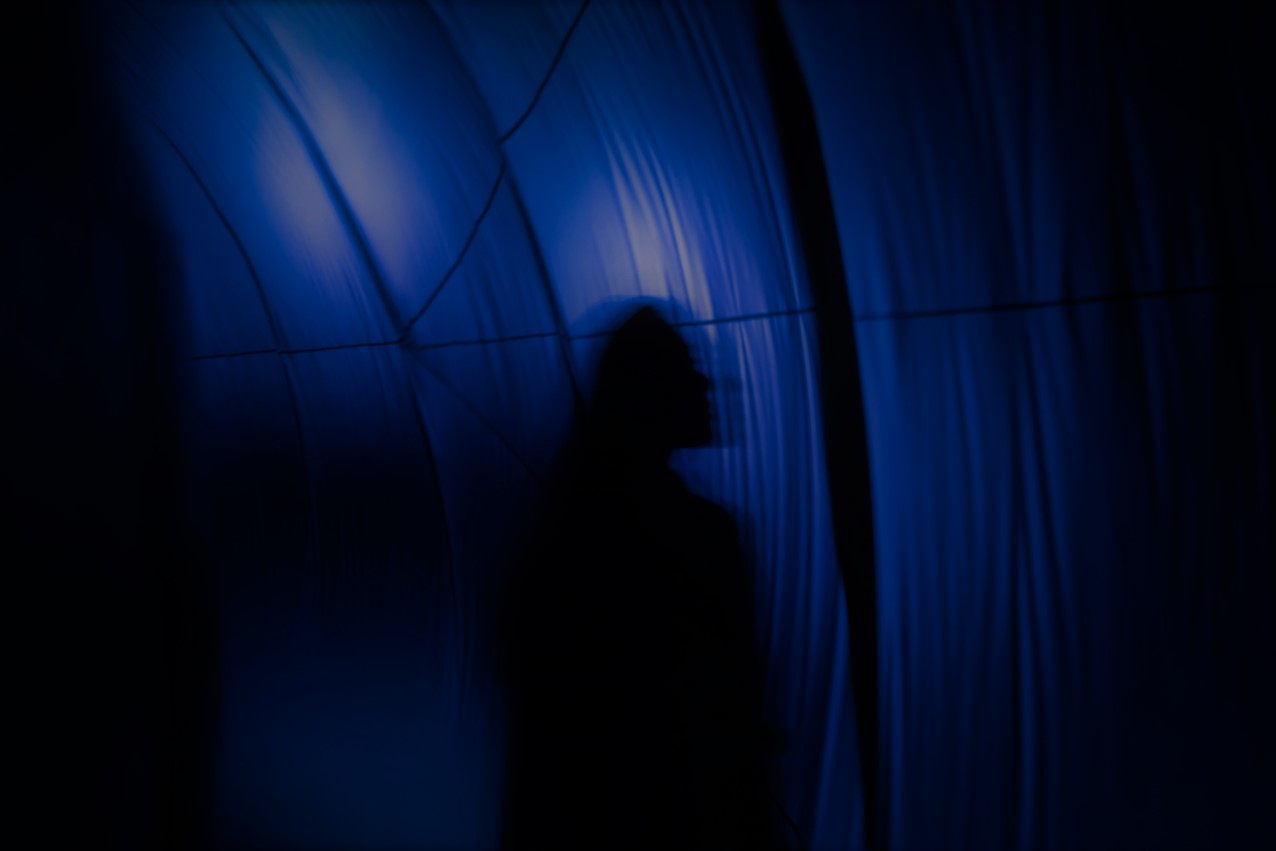

王德瑜的《No. 103》展出現場。圖/陳浡濬攝影,臺灣當代文化實驗場提供

王德瑜的《No. 103》展出現場。圖/陳浡濬攝影,臺灣當代文化實驗場提供

對此,王德瑜的《No. 103》或許注意問題的真正所在――我們對於觀看實踐和視覺性(visuality)的過度依賴。而其設想出的解方,便是徹底遮斷視覺,讓身體的知覺走在觀看的慣性之前。正如她對自己創作的重要宣稱:「走入我的作品中,不要看,不要想,只要走和觸摸」10,全黑的展場條件無疑強化了觀眾對自身在場的敏銳覺察。藉由雙環形空間中的細微聲波變化,觀眾的注意力不再導向作品的形式特質,而是他們身處其中的存有狀態。在《No. 103》的包覆下,觀眾的身體不再是一個處於內部的絕對外部者,而就是被聲響振動之力穿透、出入,徹底融入其共振網絡的一分子。以此方式,王德瑜不僅懸置人們在觀看實踐中總是自我疏離化的莫名習癖,同時也將觀眾的在場問題重新擺回作品的核心。

整體而言,「操/演現場」提供給我們的是一道班雅明式的課題:倘若「現場」就是歷史書寫的戰場,那麼每一個無法與自身休戚相關的過去,就有永遠消失的危險11。據此,究竟哪些對象值得重新召喚?以何種方式(重現、重鑄、復刻…)?而作為歷史回顧者的我們為何必須一再凝視這些對象,以至於它們能以「活物」之姿,不斷出現在當代觀眾面前?這正是蘇匯宇版本的《The White Waters》嘗試探索並回答的問題。因為如果不是今日的重啟,不是這二十多年來的反覆改版12,我們或許仍無法真正體會《白水》真正蘊含的身體展演威力。這是以田啟元為中心擴延而出的思想共振平面,叫後世無數創作者為其所牽引,創作之思也因此相互纏結。理想上,每一次的纏結都必須是一個全新的創作力點(儘管各個版本的強度不一)。同時每一輪的迴返也都昭告《The White Waters》作為基進的身體展演事件,必須重新開機。但反過來說,我們也能據此自我詰問與反思:如果新的現場不能洞見新的展演強度,如果當前的複訪衝動無法帶來真正的裂變,為何不讓經典之作繼續留在歷史裡?

這既是「操/演現場」開啟的思辨場域,同時也是有意提取藝術史力量的我們,既不能也不該輕易放下的詮釋重擔。

蘇匯宇,《The White Waters》,三頻道錄像裝置,2019。圖/陳浡濬攝影,臺灣當代文化實驗場提供

蘇匯宇,《The White Waters》,三頻道錄像裝置,2019。圖/陳浡濬攝影,臺灣當代文化實驗場提供