劇場是否總是要人沉浸?事實上,劇場最先是關於觀看。劇場(theatre)這個字源起於「theatron」,也就是「觀看的地方」。雖然,在劇場裡並不只有「觀看」,劇場中的觀看行為卻與光所營造的沉浸效果有關。現代劇場的觀者總是會在演出前等待燈的暗下,在暗處等待幕起,觀看舞臺上的光所呈現出的一個又一個畫面。畫面,就在鏡框裡,一幕又一幕地更換。在幕起與幕落間、在暗處,觀者能感覺到自己被抽離了現在,並沉浸在光所呈現的畫面裡。

現代劇場裡的燈已不是燭火,卻仍被裝飾得像是在燭臺上一樣,透過奢華的裝飾折射出燦爛的光芒。圖/Wikimedia Commons、Rudolf Simon攝影

現代劇場裡的燈已不是燭火,卻仍被裝飾得像是在燭臺上一樣,透過奢華的裝飾折射出燦爛的光芒。圖/Wikimedia Commons、Rudolf Simon攝影

在現代的鏡框劇場裡,沒有光,就不會有畫面,也就不會有觀看。劇場是光所號令的。然而,劇場裡「光」的號令卻又不能沒有沉浸在暗處的觀者。只有沉浸在暗處,觀者才能感覺到自己的「消失」。為什麼「消失」?在劇場裡,不被觀看的就像是消失的。當消失在暗處,觀者看不到其他的觀者,也不被其他觀者所觀看。不被觀看反而才有了光的「觀看」,也就是在光的號令下,去觀看光要他觀看的畫面。這一種消失在暗處並在暗處觀看的感覺,就是一種劇場的「沉浸」,「沉浸」在光要他看到的畫面裡。然而,消失的不只是觀者,還有光的技術:燈。燈揭示出的是光呈現畫面的技術。當劇場要觀者沉浸在光所展現的畫面裡,技術的暴露只會擾亂觀者的沉浸;一旦觀者看見技術,畫面就不會成為「錯覺」。因而,在舞臺上的燈,總是被隱藏在「鏡框」後。劇場的「鏡框」裡,應該只保留光要讓觀者看到的畫面。

在舞臺上的燈,因而不像觀者所在的空間裡的燈一樣,總是有奢華的裝飾,要觀者感覺自己好像仍是在一個巴洛克(Baroque)的劇場所要喚起的、已是關於光(illumination)的錯覺(illusion)裡。就算現代劇場裡的燈已不是燭火,他們仍被裝飾得像是在燭臺上一樣,即使沒有燭火的閃爍,還是能透過奢華的裝飾折射出燦爛的光芒,以喚起一個錯覺:觀者感覺在幕起前能一起暗下的好像仍是巴洛克的劇場裡一盞又一盞燭臺上的燭火,而忘了燭火是不能被一起暗下的;只有當燭火能一起暗下時,觀者才能感覺到自己的消失,並沉浸在光所呈現的畫面裡。因而,沉浸在這一意義上是一個現代的經驗,它關涉著光與在暗處的觀者。或許比起在舞臺上被隱藏在「鏡框」後的燈,觀者所在的空間裡被裝飾得像是燭臺上的燭火的燈,才更清楚地體現了這一種在現代劇場裡的沉浸是關於:所有的歷史(就像是巴洛克的劇場與劇場的歷史)只是一個光所喚起的錯覺。這一個光所喚起的錯覺卻也將在幕起前一起暗下,從而讓觀者一起消失,讓在暗處的觀者又一次沉浸在另一個光在鏡框裡所呈現的畫面――另一個現代劇場裡的錯覺之中。

當劇場在光的號令下呈現出一個又一個要觀者沉浸的畫面時,還有另一個更讓觀者感覺到自己消失的技術:從暗處升起的音樂。最先在幕起前讓觀者在暗處聽到音樂的是德國音樂家理查.華格納(Richard Wagner)為他的「樂劇」(Musikdrama)演出所設計、籌建的拜魯特節慶劇院(Bayreuth Festspielhaus)。雖然這或許只是一個意外的失誤,華格納卻已設想過在暗處的觀者所能感受的「沉浸」。除了光,華格納更關注的是音樂。華格納最為人所知的事實上就是他對「總體藝術」(Gesamtkunstwerk)的想像。此前的歌劇,雖然涵括了詩、音樂、舞蹈及戲劇等,仍不是他所想像的「總體藝術」。華格納所想像的「總體」不只是所有藝術的總集,而是一個能讓所有藝術間的界線消失的「整體」。要能讓所有的藝術成為一個「整體」,他認為最為關鍵的藝術就是音樂。華格納認為,只有音樂最能消除所有藝術間的界線。因而,華格納要的並不是「歌劇」(Oper)而是「樂劇」(Musikdrama),一個以音樂讓所有藝術的界線在劇場裡消失而成為「整體」的「總體藝術」。華格納對「總體藝術」的想像(與其所透露出的藝術與政治極為複雜的關係)已有許多討論與詮釋,其為實現這一「總體藝術」所設計的拜魯特節慶劇院或許已清楚體現了這一想像的關鍵:在暗處的觀者,不只是沉浸在光所呈現的畫面裡,更是沉浸在從暗處升起的音樂裡。當許多劇場將音樂家的空間設計在舞臺前,華格納則在拜魯特節慶劇院裡將音樂家的空間設計在舞臺下,這是為了讓觀者更能沉浸在從暗處升起的音樂中。在暗處的觀者,並不只是因為不被觀看而感覺消失,更是在音樂裡感覺到自己的消失。

當時,音樂被認為是最能清楚體現出「存有」的藝術,而「存有」則被認為是「變動」――就像是人的「存有」,總是在「變動」裡,這一個現在的自己和下一個現在的自己總是不一樣。人,是到向死亡的存有。在到向死亡時,存有在變動裡到向消失。音樂的消失,就像是存有的死亡。因而,沉浸在音樂裡的聽者總是能感覺到自己到向死亡的存有像是消失在到向消失的音樂裡。然而,當音樂被認為是最能體現出人這一個「變動的存有」的藝術,它也被認為有一種「精神」:「存有」能不只是在變動裡,更能讓自身在變動裡返回自身、確認自身、從而不只是受制於變動。沉浸在音樂裡的聽,能讓人感受到這一種「精神」。聽者能在音樂裡不斷感受到「轉變」,更重要的是,在現代和聲學建立後,音樂裡的這一些轉變已不只是隨意的變動,而更像是一種音樂對「轉變」的慾望。這一個慾望,或許就是到向現代和聲學所建立的「主音」。在音樂無論怎麼變動仍要以「主音」結束的意義下,音樂的慾望就是對「主音」的慾望。在音樂到向「主音」的慾望下,音樂的轉變仍要經過許多偏離與抗爭,這一些偏離與抗爭讓音樂更像是人的「存有」,一個慾望著「轉變」的存有。在這,「存有」已不只是受制於變動的存有,而是一個慾望著「轉變」的存有。

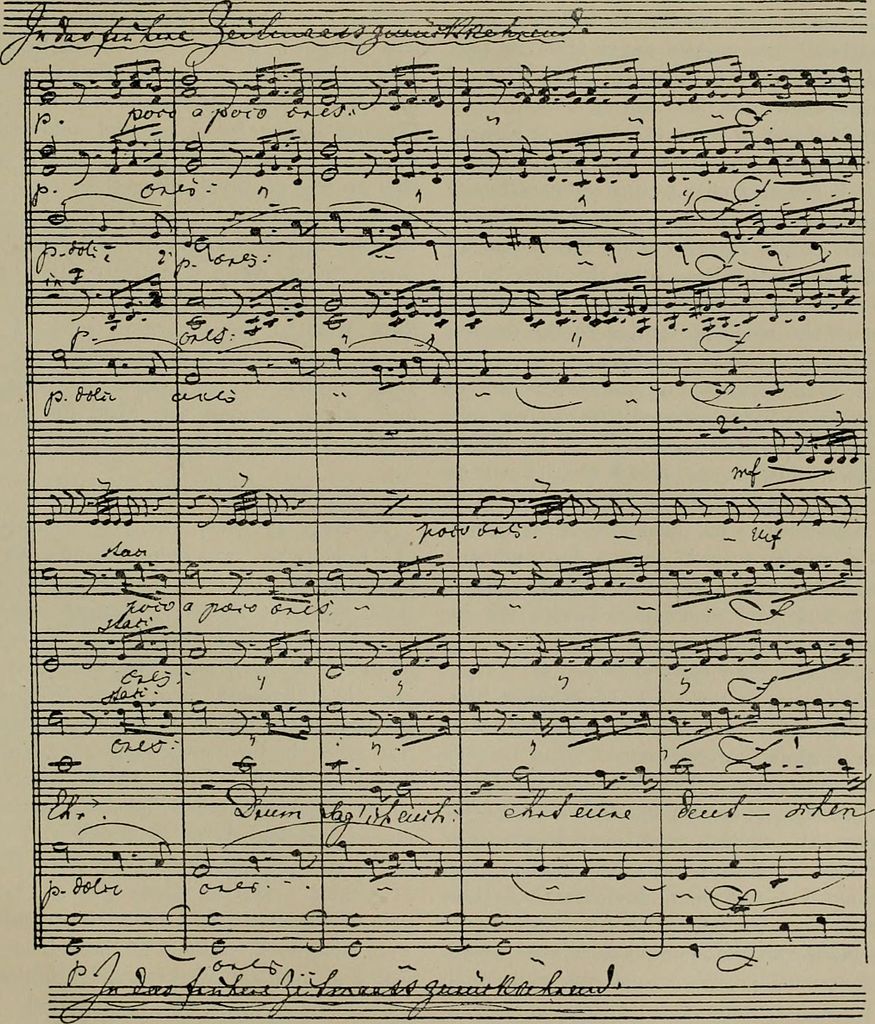

華格納《名歌手》(Die Meistersinger)樂譜手稿。圖/Internet Archive Book Images;摘自《Modern Music and Musicians》的掃描頁面,畫質可能因數位化而有所調整

華格納《名歌手》(Die Meistersinger)樂譜手稿。圖/Internet Archive Book Images;摘自《Modern Music and Musicians》的掃描頁面,畫質可能因數位化而有所調整

雖然,音樂就像到向死亡的存有一樣會消失,存有所慾望的轉變卻讓「消失」有了不一樣的意義。隨著音樂的消失,到向「主音」的音樂,體現的是存有的「精神」。「變動」是起於音樂的消失;「轉變」卻是關涉著音樂的慾望。是音樂的慾望(這一種經過偏離、抗爭而要到向「主音」的慾望)才讓「變動」不只是「變動」而更是「轉變」。在這層意義下,消失的音樂逐漸被感受為並不真的消失,事實上,反而是音樂的「消失」才讓音樂在「變動」裡,從而能有音樂所慾望的「轉變」;是音樂的消失,才成就了存有的精神。被認為體現了人的存有的音樂,反而又成為一種對人的存有的想像:人的存有就像是音樂一樣,不應該只是到向死亡而在變動裡,受制於變動;比起存有到向死亡的變動,更重要的是存有所慾望的轉變,是轉變才成就了存有的精神。要能成就存有的「精神」,存有就要能像音樂一樣,在經過許多偏離與抗爭後,越過存有的限制――死亡與到向死亡的變動,返回自身、確認自身,從而讓存有「轉變」。在這一意義下,音樂被認為是「存有就是轉變」的體現。因而,除了音樂的消失像是存有的死亡,音樂的慾望更像是存有的慾望、音樂的轉變更像是存有的轉變,音樂的精神也更像是存有的精神。當音樂以轉變體現了存有的精神,存有的精神已並不只是音樂家這一個「個別存有者」(being)的精神,而更是越過「個別存有者」的限制的另一個「更大的存有」(Being)的精神。因而,被感受為消失的音樂並不真的消失,反而是消失才成就了精神。當消失的音樂逐漸讓聽者感覺到自己的存有像是會消失在音樂裡,就是消失在音樂的精神裡、消失在存有的精神裡,從而成為音樂的精神、成為存有的精神。沉浸在音樂裡,事實上就是讓自己的這一個「個別的存有」消失,從而成就另一個「更大的存有」的精神,而在華格納的「樂劇」與他所想像的「總體藝術」裡,這一個精神就是「德意志」(Deutsch)的精神。

華格納完成的第一齣樂劇《崔斯坦與伊索德》(Tristan und Isolde),首演於1865年。圖/Wikimedia Commons、Joseph Albert攝影

華格納完成的第一齣樂劇《崔斯坦與伊索德》(Tristan und Isolde),首演於1865年。圖/Wikimedia Commons、Joseph Albert攝影

精神,這一個在西方與靈魂、氣息有關的詞,總是關涉著一種對「聲音」的想像:聲音和氣息有關,從聲音能聽到氣息,從氣息能聽到靈魂。聽見一個人的聲音,總是比看見一個人,更能感受到他的靈魂。聲音的變動透露出的是氣息的變動、氣息的變動透露出的又是靈魂的變動。更重要的是,讓聲音能被聽見的氣息是能被身體感受的――就像是風的輕觸。因而,藉著氣息,聲音以至於靈魂,都像是能被身體感受。當存有的精神在西方的談論裡總像是離開身體的,音樂對精神的體現,則讓這一個總是離開身體的存有的精神能被存有的身體感受。身體感受著音樂,這一個身體對音樂的感受,卻又讓聽者覺得身體在消失,消失在他以身體感受的音樂裡。這就是「沉浸在音樂裡的聽」所喚起的一個不像是錯覺的錯覺:身體感覺像是消失在音樂裡是一個錯覺,是因為身體並不真的消失在音樂裡,是因為音樂仍要身體的感受;然而,卻又是因為仍在感受著音樂的身體,讓這一個錯覺不像是錯覺。「沉浸在音樂裡的身體像是消失在精神裡」這一個不像是錯覺的錯覺,就是在華格納想像的「總體藝術」裡,音樂能讓所有藝術的界線消失在劇場中的關鍵。畢竟,音樂能讓自己這一個「個別的存有」消失,當然就能讓所有藝術的界線消失,從而成就另一個「更大的存有」(亦即,德意志)的精神。在暗處的觀者,因而不只是沉浸在光所呈現的畫面裡,而更是沉浸在音樂裡,消失在精神裡。

或許曾經沉浸在華格納的樂劇的希特勒(Adolf Hitler)就是在這種對精神的慾望下,讓政治成為了藝術,讓存有沉浸在政治的藝術裡。政治所慾望的德意志精神,成為了身體所能感受的藝術的精神。然而,就像是華格納的音樂所慾望的精神,這一個身體所能感受的精神又要讓身體感覺像是消失。因為,只有當這一個「個別的存有」消失時,才能成就另一個「更大的存有」的精神。而這一個「身體將消失在德意志的精神裡」的錯覺,或許最後就體現在納粹所發動的戰爭裡。就像是德國哲學家與文化學家華特.班雅明(Walter Benjamin),這一個顯然對當時政治與藝術的變動有最深的身體感受的靈魂所觀察到的,或許戰爭才是最後的「總體藝術」。

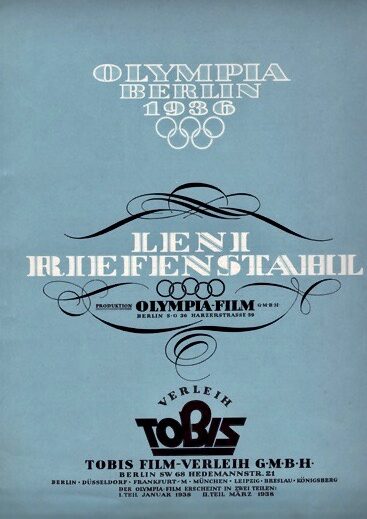

由電影發行商TOBIS Film-Verleih G.m.b.H.於1937/1938年出版的電影《奧林匹亞》小冊封底。圖/Wikimedia Commons

由電影發行商TOBIS Film-Verleih G.m.b.H.於1937/1938年出版的電影《奧林匹亞》小冊封底。圖/Wikimedia Commons

確實,戰爭就是一個需要身體,更需要身體沉浸以至於消失的「總體藝術」。就納粹而言,戰爭為的就是要成就德意志的精神,一個更大的存有的精神。然而,這並不是指身體就不重要。就像在華格納的樂劇裡,是感受音樂的身體讓這一個身體像是消失的錯覺不似錯覺,在納粹的「總體藝術」裡,身體反而在光裡被呈現為一個又一個畫面――就像是德國導演蘭妮.萊芬斯坦(Leni Riefenstahl)為納粹舉辦的奧林匹亞(Olympia)所拍攝的許多畫面。納粹要的身體,是要能像音樂一樣慾望著精神的身體,是要能越過存有到向死亡的「變動」而慾望著「轉變」的身體。或許一個能越過存有到向死亡的「變動」而慾望著「轉變」的身體,比起「個別的存有」的身體要更能體現出德意志的精神,才因此被拍攝下來、在光裡成為畫面。就像是萊芬斯坦為奧林匹亞所拍攝的跳水運動員,他們在畫面裡,最後已不像是在跳水,而像是在飛越。萊芬斯坦藉著一個又一個運動員起跳的畫面,讓他們彷彿飛越整個天空,讓觀者分不清他們究竟是在飛越或是落下。

只是這一個由光所呈現、讓身體能不斷飛越天空而從不落下的錯覺,已不是發生在華格納為他的樂劇所設計的拜魯特節慶劇院中那劇場的鏡框裡。就像是納粹所舉辦的奧林匹亞,納粹最後所發動的戰爭,是一個離開了劇場、離開了鏡框的「總體藝術」,是更總體的總體,更沉浸的沉浸。感受著精神而感覺像是要消失在精神裡的身體,究竟是飛越,還是落下?存有所慾望的轉變,轉變所成就的精神,是在光裡,或是在暗處?