日本科技藝術團隊teamLab的作品,讓觀眾沉浸於美麗的影像世界,隨著身體的移動,觸發影像的改變,手一碰,一隻蝴蝶便翩翩起舞,身體一靠近,充滿日本古典畫風的海洋牆壁,海浪又勾起一陣波瀾。這是許多人認識「沉浸式藝術」的第一個體驗,既有互動的娛樂又有感官的饗宴。

然而,「沉浸」這個詞是屬於新時代的詞彙?是因為新科技發展才出現的美學概念嗎?還是它其實在藝術史上,已經有一定程度的發展,或者是科技和資訊界早已預示的發展方向?而我們又有什麼觀看沉浸式藝術的視角呢?以下將從電影、戲劇的角度,重新思考「沉浸式藝術」這個名詞的意義與內涵,並試圖回答沉浸式藝術的重要宣稱,像是:虛擬實境電影製作出傳統電影無法達成的「感官經驗」與「互動性」,與傳統美學的差別何在?沉浸式劇場、參與式劇場與環境劇場在媒體中混用的情形是因為概念的關聯性,還是只為搭上潮流的列車?對於沉浸式藝術的推崇,是否只是每次新科技出來後,社會經常出現的盲目崇拜現象,還是這種藝術形式真的能成為一種具有創造性的改變?沉浸式藝術在「當代藝術」、「新媒體藝術」或「科技藝術」的領域之中,到底是不是一個重要的名詞,還是又是一個轉瞬即逝的流行用語?

teamLab的作品《Black Waves: Lost, Immersed and Reborn》於西班牙馬德里Espacio Fundación Telefónica 展覽現場,2019。圖/黃祥昀攝影

teamLab的作品《Black Waves: Lost, Immersed and Reborn》於西班牙馬德里Espacio Fundación Telefónica 展覽現場,2019。圖/黃祥昀攝影

提到沉浸式電影的時候,通常都是指「虛擬實境電影」,因為當觀眾戴上VR裝置、進入360度的影像和環繞聲響中,便似完全沉浸在另一個世界。圖/黃祥昀攝影

提到沉浸式電影的時候,通常都是指「虛擬實境電影」,因為當觀眾戴上VR裝置、進入360度的影像和環繞聲響中,便似完全沉浸在另一個世界。圖/黃祥昀攝影

如果搜尋媒體中的文章,「沉浸式藝術」這個詞使用的範圍非常廣泛。以使用的「媒介」來區分的話,可以分成至少由小說、劇場、電影、科技藝術類的環繞式裝置。最寬廣的意義是讀一本小說或者看一場表演的沉浸,在這邊的沉浸通常就是專心投入的同義詞;更進一步的話,一些文學理論出身的學者,會去分析文學中的故事劇情與敘事方式如何讓觀眾沉浸其中,這樣的敘事分析也被應用於傳統的在黑暗電影院中看的電影、靜坐劇院裡觀賞的劇場表演。相較於此,當下潮流所描述的「沉浸式劇場」指的比較接近空間與感官的沉浸,而非透過想像力加上專注而投入一本小說(敘事)的沉浸。在沉浸式劇場中的觀眾需要在劇場空間走來走去、東看西看,最著名的莫過於改編自莎士比亞的《馬克白》的《Sleep No More》,媒體提及此作時都會特別標示:這是一種沉浸劇場「體驗」,打破觀眾跟演員的距離。

而在提到沉浸式電影的時候,通常都是指「虛擬實境電影」,因為當觀眾戴上VR裝置、進入360度的影像和環繞聲響中,便似完全沉浸在另一個世界,有時候甚至還會有互動與觸覺跟嗅覺的體驗。在強調整個身體與全方位的感官體驗的面向上,像是科技藝術的空間(互動)沉浸體驗,如日本teamLab的作品也有異曲同工之處。只不過虛擬實境是藉由頭套裝置,彷彿於虛擬空間行走,而teamLab作品則是在真實空間行走,但是透過佈滿整個空間的投影和精緻的互動,沉浸到另一個世界中。

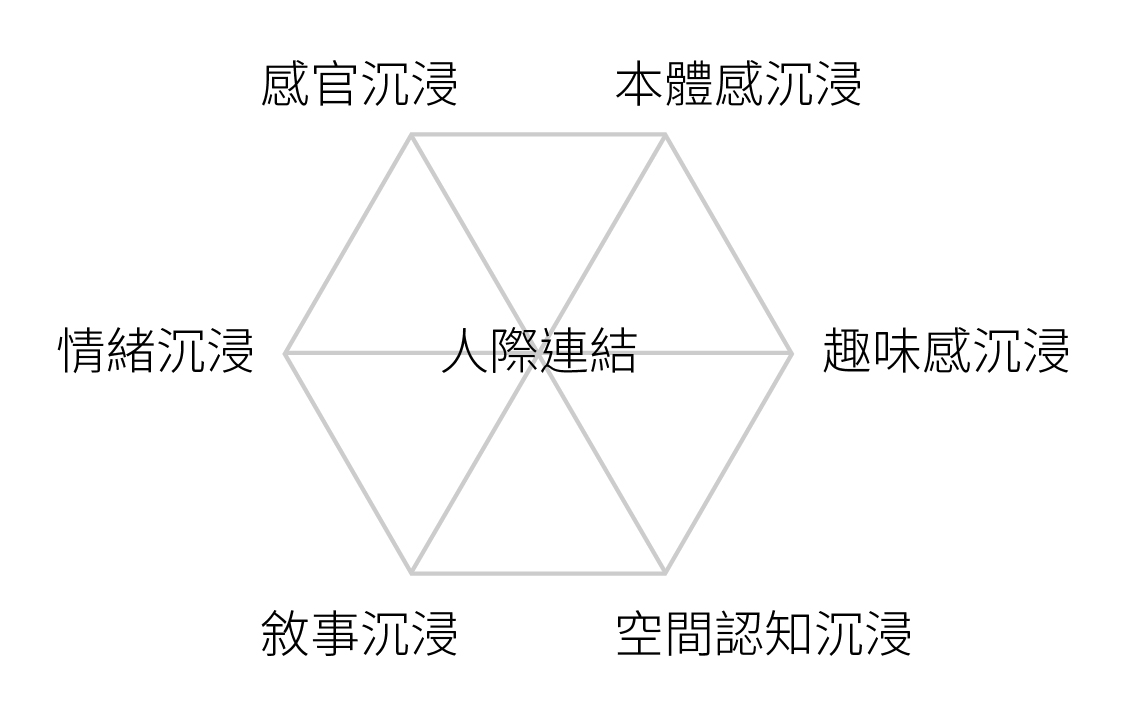

如果用「沉浸對象」來區分,可以分為以下六種不同類型的沉浸:感官、本體感、趣味感、空間認知、敘事、情緒。1這六種沉浸不是互相排斥的概念,其實時常被混用,或者同時存在一件藝術作品之中。除了這六種以外,我認為還有必要加入「時間沉浸」這個類型,像是在觀看某些虛擬實境作品時,觀眾的身體其實並沒有移動,而空間認知跟時間概念是緊密相連的另一個面向。以下將針對具體的藝術作品,分析它們如何創造哪種意義下的沉浸。

近年來除了虛擬實境電影直接內建證成被貼上沉浸式標籤外,不少多頻道動態影像作品2也都會被貼上「沉浸」的標籤,像是2019年的威尼斯雙年展臺灣館代表藝術家鄭淑麗的作品《3×3×6》就被形容成一種「沉浸式」裝置作品3,因為觀眾可以橫跨展間,被各種螢幕環繞,其中一個展間更設計成像圓形的監獄結構,觀眾可以站在中間觀看影像。

環繞式多頻道錄像這個形式本身,也成了沉浸式的另一種代表形式。在許多藝術評論中,也會把這個形式跟觀眾的「入戲」與「出戲」狀態結合,這時候「沉浸」的定義就跟傳統電影敘事學或者文學敘事學的關聯性比較接近。例如,吳牧青、嚴瀟瀟共同撰寫的文章〈台北當代藝術館「影像的謀反」――為返而反,造「返」有理,重新入戲〉,就將多頻道錄像的作品跟「入戲」與「出戲」合併討論,他們寫到:「她(指策展人黃香凝)將具體議題與美學形式上的探討相結合,在『影像的謀反』一展中,透過對不同面向上感知的強調,反對單一的官方敘事,叩問了包含聲音在內的影像的本質。而錄像敘事的迴歸,正是此展題旨內在虛構/非虛構情節包覆、拆解與重組間,重新在入戲與疏離之間,提出見所未見、聞所未聞的『重新入戲』箴言。」4

鄭淑麗,《3×3×6》,2019,複合媒材裝置。圖/林冠名攝影、藝術家及臺北市立美術館提供

鄭淑麗,《3×3×6》,2019,複合媒材裝置。圖/林冠名攝影、藝術家及臺北市立美術館提供

回應上述對於台北當代藝術館「影像的謀反」展中出戲與入戲的討論,在電影理論的脈絡中,1960年代的「擴延電影運動」(Expanded Cinema Movement)5受到社會學影響的觀眾理論,認為觀眾若是坐在黑暗的電影院裡面看電影,全盤接受電影所表達的故事以及意識形態,會讓觀眾失去批判的能力,因此推崇多頻道螢幕與設計讓觀眾在作品之間走動的展演形式,也為「出戲」找到價值,常用的手法是把電影設備納入影像之中,或者,使用讓人出戲的畫外音,使觀眾意識到自己在看的是虛幻的電影(illusion),不至於完全「沉浸」在電影的情節之中,因而不會對電影的意識形態直接買單。6以這種觀點來看,進入到虛擬實境電影,沉浸跟幻覺的關聯性又更高,在討論虛擬實境形上學的書中,邁克爾.海姆(Michael Heim)如此定義虛擬實境:「具有三維聲光效果的音頻系統能夠增強沉浸於虛擬世界中的幻覺。也就是說,幻覺便是沉浸。根據這種觀點,虛擬實在意味著在一個虛擬環境中的感官沉浸。」7上述的定義,指涉到了感官與空間方面的沉浸,但是在關於觀眾與擴延電影的脈絡中所講的沉浸,其實應該更關乎到底觀眾是被動還是主動地觀看(passive or active spectatorship)?是出戲還是入戲?在擴延電影理論的文獻中,當討論到像是多頻道或者環繞型電影、圓球投影型電影,才真正使用到沉浸(immersive)這個詞。而討論虛擬實境電影的文本都不證自明的直接用沉浸這個詞彙。也就是說,在中文裡面沉浸有投入專心的意思,但不一定每一次都指涉到環繞性幻覺、整體環境的籠罩,或者身體與影像互動後所形成的感知經驗事件 。8也就是這樣的混淆,讓中文世界的藝術文章濫用了沉浸美學的字眼。

「影像的謀反」(The Rebellion of Moving Image)展中朱利安(Isaac Julien)的作品《 萬重浪》 現場裝置照。圖/台北當代藝術館(MOCA Taipei)提供

「影像的謀反」(The Rebellion of Moving Image)展中朱利安(Isaac Julien)的作品《 萬重浪》 現場裝置照。圖/台北當代藝術館(MOCA Taipei)提供

回到聚焦於媒體藝術的發展,在電影院中觀看電影是透過「電影的敘事」以及電影院的「黑暗環境」,讓觀眾深深「入戲」,而美術館的多頻道錄像藝術或者環繞型影像裝置,則讓人在走動之中「出戲」,因為要不斷地選擇看哪邊,還要很忙碌地一直走動,但卻有一種因為環繞與走動產生的空間沉浸、身體感官的沉浸。

而當傳統電影院的電影,發展到所謂的虛擬實境電影之後,我們又該如何重新思考電影的定義與沉浸的意涵?電影導演史蒂芬.史匹柏(Steven Spielberg)在剛開始接觸虛擬實境的時候並不喜歡,他表示:「我覺得我們正在進入一項稱之為虛擬實境的危險媒介。」「我之所以認為它危險的唯一理由,是因為它賦予觀眾(viewers)許多新的觀看空間,不再得遵從說故事的人(story tellers)的指示,觀眾可以選擇自己要看哪裡。」而這同時也讓說故事的人失去了主導觀眾視角的權力。9蔡明亮導演也表示:「VR的特性很好玩,就是單純為了一個觀眾而生,觀眾可以選擇看場景,也可以選擇看演員。因此,這對於演員來說也是一大挑戰,片中女主角尹馨就認為,拍攝VR電影時的表演難度更高,沒有固定的鏡頭可以看,要讓自己直接成為空間的一部分,這也會比較類似劇場的表演方式。」10若用比較理論的說法,電影學者孫松榮解釋:「對場面調度者而言,與其說不存在一種絕對鏡位的鏡頭,倒不如說只有讓後觀眾(或其主觀視角)恣意選取觀看的畫面。」11

電影史與理論學者史惟筑在〈電影語彙與VR電影的思索〉一文中,將傳統電影敘事中的銀幕框與虛擬實境電影中的視域做比較。在傳統電影中,銀幕框是電影敘事中觀點的邊界,景框外與景框內的設計,也是創造故事軸線重要的考量,但是在虛擬實境電影中,因為是360度,所以已經沒有邊框的限制。12

史惟筑論證儘管傳統電影跟虛擬實境電影媒介本身有不同的限制,但是要不要使用景框的概念其實還是可以由導演與編劇決定、或者可以說內容還是有一定的決定權(也就是說,內容跟形式兩者並非二元對立。但在此先暫且做此區分)。史惟筑舉法國導演亞利桑德.貝爾茲(Alexandre Perez)製作的虛擬實境電影《Sergent James》為例,其將場景設定在床底下,透過躲在床下的主角的視角展開故事,因此,仍使用了傳統景框的概念在電影之中。由廖克發導演的《羽》則是讓觀者用俯視的角度,觀察人物生活的樣子並沉浸在像夢境邊的漂浮狀態。13

上述從電影理論出身的學者和電影導演,都傾向從觀眾的選擇觀看角度與導演的掌控敘事權之間的張力去分析虛擬實境電影。而觀眾對影像的選擇跟互動性,是虛擬實境電影相較於傳統電影多出來的一個媒介特性,這個互動特性和沉浸的第一種意義「專心投入」,在某些條件下會產生矛盾,但從另一方面看,如果是習慣互動的數位時代,很可能互動作為一種新型態的敘事和沉浸本身並非抵觸。因此,感官經驗的實際內容,和互動設計的具體手法,才是沉浸式美學未來的研究重點。

《留給未來的殘影》劇照,圖中舞者為潘柏伶、方妤婷。圖/李孟庭攝影、高雄市電影館提供

《留給未來的殘影》劇照,圖中舞者為潘柏伶、方妤婷。圖/李孟庭攝影、高雄市電影館提供

從身體現象學的角度切入上述的討論,哲學學者龔卓軍討論VR的互動設計如何影響觀眾的沉浸程度,在〈那團火,那縷煙,反沉浸的沉浸:《留給未來的殘影》與VR電影的本體感操演〉一文中,龔卓軍認為VR電影敘事最重要的考量是如何創造不同的身體情境但還能使觀眾入戲,並持續維持沉浸的狀態。14龔卓軍寫到:「由於觀眾透過頭顯進入的是某種沉浸式的情境,因此,如何在觀眾戴著頭顯的轉身之際,維持這種沉浸感、存在感的本體感對焦,進而滑入某種心理與情感處境,又能夠順利轉換到不同的場景,以不同的身體姿態,進行本體感對焦的情境轉換,就成為VR電影沉浸感是否被破壞,導致觀眾體驗出戲的關鍵操作與基本感覺邏輯。」15

在這篇文章中,其實龔卓軍預設了一項美學標準,互動性可能與電影感互相違背,因為過多的或設計不良的互動,容易讓人出戲,會讓人覺得缺少電影感,但他也特別用引號把「電影感」標示出來,表示這涉及了電影本身定義的擴張,也引領我們思考另外的問題:是否虛擬實境這項技術的出現,會讓我們能夠建立一套新的電影美學?這套美學可能是奠基在沉浸式「互動」和「感知經驗」的擴張,而不是偏重於傳統電影中的敘事邏輯所促成的沉浸?

除了沉浸式電影之外,當今的許多劇場作品也都會被貼上沉浸式的標籤,許多藝術評論文章也將沉浸式劇場跟環境劇場(environmental theater)、場域特定表演(site-specific performance)、參與式劇場(participatory theater)混用,雖然這些表演形式也涉及觀眾的參與,讓演員在觀眾之間走動,打破舞台的隔閡,但是其實應該要依照作品的內容、年代和脈絡,將不同的作品分類,而不是只因為打破舞台概念或因為在戶外演出,就直接歸之為沉浸式劇場。

場域特定表演(site-specific performance)最早的脈絡是1960年代興起的當代藝術理論,相較於空間(space)與地方(place),使用場域(site)這個字眼,在一般字義所指涉的是更具體的位置、現場、或實際發生事件的場所。這個概念的其中一個脈絡是極簡主義的雕塑理論,這種美學認為觀眾所看到的作品與作品的環境才是主體,而不是藝術家。16如果把作品移動位置,就等於是毀掉了作品。17在這個意義上,觀眾的參與本身是完成作品的條件。

這個概念應用到劇場上,就變成表演的場域是劇情的重要元素,一齣劇一定要在某個地方演出,才能讓作品完成,如果換地方表演便不完整。而環境劇場中對於環境的定義更廣泛,包括劇場所選的場域、劇場的道具、售票處、廁所、燈光、演員的服裝、演員本身,也就是整個環境中只要是影響觀眾的經驗都屬於「環境」的一環。18環境劇場的理論也可以連到更早的偶發行為藝術(happenings)。到1970年代以後,講到環境通常會加上生態這層意義。19由於環境劇場強調劇場的所有元素站在一個平等的位置,擁有自己的語言,為自己發聲,觀眾能作為劇中主角,舞台、道具也可以是主角,和演員的地位同等重要20,因此,延伸到生態永續發展的觀念,就變成一種讓所有人類與非人類有平等對話的可能性的劇場,也是一種互為主體的概念。

這種對互為主體的追求、創造與他者對話的平台也跟參與式劇場的初衷不謀而合。最著名的參與式劇場理論,是在討論如何再現或者直接與被壓迫者對話。這種觀眾的參與度,不像是場域特定藝術(site-specific art)預設的抽象的理論性觀眾,或者在某些情況下還是有某種意識形態,使觀眾的定義其實限縮在會去戶外藝術季的中產階級觀眾,被壓迫者劇場聚焦在真實的人事物身上,跟社會現實緊密連結。環境劇場後來加入生態學與後人類的意義,並與有社會學視角的被壓迫者劇場有關聯性,並非斷裂地偶然。

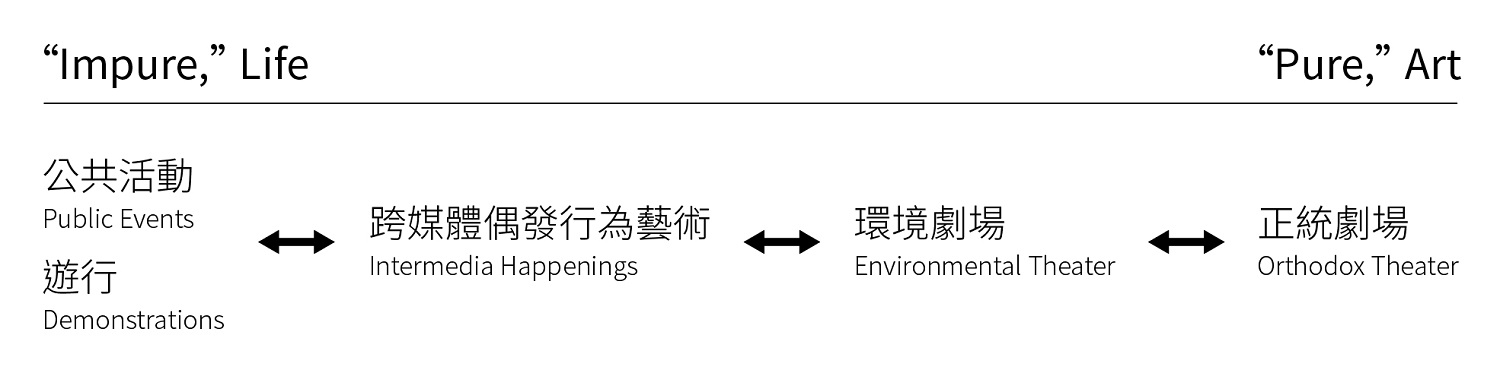

理查.謝喜納(Richard Schechner)在其《環境劇場》(Environmental Theater)一書中,提出了劇場類型的光譜,從接近生活的公共活動,到一般人認為的「純」藝術,也就是劇場裡面的表演。21

從「不純粹」的生活到「純」藝術:22

圖/黃祥昀製圖

圖/黃祥昀製圖

然而沉浸式劇場在什麼意義下跟之前的劇場類型有關聯?由於目前關於沉浸式劇場的論述還正在發展中,而且橫跨劇場理論、電影理論與新媒體理論,還未能有一個系統。但根據我初步的研究結果,在討論沉浸時,要回到前述中所分的六大類型去思索,並要理解沉浸的概念也是一種光譜,也就是關於「沉浸程度」的問題,再分門別類討論敘事、感官、互動、情緒等等的沉浸更細緻的差異。我認為在講沉浸式劇場時,強調感官沉浸與時空沉浸的劇場,才比較適合被貼上沉浸式的標籤,其餘可能在考量內容與劇情之後,比較接近「環境劇場」,不一定有必要使用沉浸這個詞。若是使用遊戲規則、又讓觀眾可以到處走動,可能比較適合稱之趣味感沉浸,開啟的是另一面向的討論。儘管不同類型的沉浸可能出現在同一個作品中,但這終究只是一個標籤,形式與內容的綜合討論,才比較具有意義,因為媒介本身的特性,還是要依照其出現的脈絡跟觀眾而定,並沒有什麼本質不變的沉浸式藝術,或只有某種科技才能達到的必然特性,除非沉浸的概念能對作品帶來新的理解與詮釋,要不然終究只是一種潮流的用語。未來的研究重點應該是從互動性敘事、身體感知與新媒體的領域,繼續釐清沉浸式的概念,或找到更精確的詞彙,以具體的作品為出發點,才能真正找回理解當代沉浸式藝術的基礎。