Ars Electronica Center in Linz, Austria, an iconic institution in the field of new media art, launched an exhibition, Genetic Art – Artificial Life, in as early as 1993, and the symposium held in the same year included topics like “Gentechonology” and “Lust for Immortality: Cloning, Cryonics and Cosmetics.”1 In 2015, PSX Consultancy (The Plant Sex Consultancy), a collaborative project by Taiwanese artist LIN Pei-Ying and Slovenian artist Špela PETRIČ et al., received an Honorary Mention in the Hybrid Arts Category of Ars Electronica. At the same festival in 2019, Tiger Penis Project by Taiwanese artist KU Kuang-Yi was selected for the themed exhibition, Human Limitations – Limited Humanity. Over the last two decades, with interdisciplinary endeavors to bridge the distances between art, technology, and science being encouraged more than ever in Western societies, various works and ideas of BioArt have sprung up like mushrooms after the rain [Translator’s note: The original text uses both bamboo shoots and mushrooms after the rain as metaphorical expression and suggests that mushrooms be more apt in the context of Bio Art.]. But what kinds of qualities make an artwork BioArt? How do we draw the boundaries of BioArt in myriads of discussions on intersecting art with science? This article investigates incidents “indicative” of developments of BioArt since the 1930s. We will also look into the past works and theories of Brazilian-American artist Eduardo KAC, who coined the term “bio art,” in order to paint a better picture of this contemporary art practice.

In 1936, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) held an unprecedented exhibition, Steichen Delphiniums, to showcase rare varieties of real delphiniums. These flowers came through decades of meticulous crossbreeding and research by Edward STEICHEN, a renowned photographer and horticulturist. Prior to planting, the seeds of these delphiniums were soaked in colchicine solutions to induce genetic mutations in cells. Then, from the resultant hybrids, STEICHEN selected taller plants with blooms of unusual colors, such as fog blue and lavender, to display in the exhibition halls of the museum. With the focus of “develop[ing] the ultimate aesthetic possibilities of the delphinium,” STEICHEN’s labor of love of 26 years was presented to the public for the first time. The MoMA press release for this groundbreaking show specifically emphasized that “[t]o avoid confusion, it should be noted that the actual delphiniums will be shown in the Museum – not paintings or photographs of them.”2

STEICHEN exhibited his crossbred delphiniums at a time when the modernists were still debating about the nature of artistic materials and the practical functions of art. Later, in 1949, he wrote in The Garden magazine:3

With artists continuing to explore possibilities of mediums and innovative creative expressions, living materials including plants and animals began to appear in subsequent artworks. Largely influenced by Dadaism and gaining currency in the 1920s, surrealism drew inspiration from Sigmund FREUD’s psychoanalytic theories and discoveries of previous scientists, seeking creative expressions free of constraints of rationality, conventional aesthetics, and moral values. In 1938, French surrealist artist André BRETON and Paul ÉLUARD co-organized the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme. At the exhibition, in his installation piece Rainy Taxi, Salvador DALÍ used live snails and set them to crawl on the mannequins in the car. It is generally agreed that STEICHEN and DALÍ were among the early artists who utilized living creatures in their artworks, which provoked later discussions of artistic expressions with “biomaterials” as artistic mediums.

During the 1950s to 1970s, independently developed art movements—such as action painting, happening, Fluxus, and Viennese Actionism—sprang to the scene. The new generation of artists looked for artistic methods that were more conceptual and reflective of social reality; they also embraced unconventional mediums and creative processes. Jannis KOUNELLIS, a pioneer of Arte Povera, exhibited a living horse in 1969; in 1974, Joseph BEUYS stayed in the same room with a coyote for his performance I Like America and America Likes Me to address standoffs within the United States over the Vietnam War and racial conflicts; the Viennese Actionists saw their physical bodies as creative tools, using bodily fluids, human wastes, and blood in their works to push the boundaries of moral taboos; Hans HAACKE, an artist and leading figure of Institutional Critique, incorporated the concept of ecosystem including living organisms and their environments in his works. Some of the works created during this period still look daring and bold today. However, they all stemmed from the experimentations with mediums, creative processes, and artistic expressions in the early 20th century that caused fundamental changes in people’s understanding of creative mediums and the relations between audience and artworks.

Špela PETRIČ, Confronting Vegetal Otherness - Skotopoiesis, Phytoteratology, Strange Encounters. Photo courtesy of Špela PETRIČ and Ars Electronica

Špela PETRIČ, Confronting Vegetal Otherness - Skotopoiesis, Phytoteratology, Strange Encounters. Photo courtesy of Špela PETRIČ and Ars Electronica

For centuries, art and science had been deeply connected in the Western world. Not until the emergence of modern science did the two be forced to drift apart into distinctive fields. Now, the emphasis on technoscience in the present era brought crossover possibilities between the two fields. As technology and science gradually became the indispensable foundation of modern society in the past 30 years, collaborations between artists and scientists increased significantly.4

Cross-disciplinary collaboration between art and science is nothing new. Alexander FLEMING, a Scottish physician and microbiologist who discovered penicillin in 1928, was as passionate about painting as he was about scientific research. He cultured various microorganisms on agar, and arranged them—according to their different natural pigments, growth rates, and features – into patterns to create paintings on petri dishes. Hungarian artist György KEPES was influenced by the Bauhaus movement before he went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Out of a strong interest in abstract art, he started to explore the abstract and artistic qualities in scientific imagery. After the Second World War, KEPES displayed his research on scientific imagery in an art exhibition at the MIT, committed to bringing art, science, and technology together ever since.

Alexander FLEMING was as passionate about painting as he was about scientific research. He cultured various microorganisms and arranged them into patterns to create paintings on petri dishes. Photo courtesy of Alexander Fleming Laboratory Museum (Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust)

Alexander FLEMING was as passionate about painting as he was about scientific research. He cultured various microorganisms and arranged them into patterns to create paintings on petri dishes. Photo courtesy of Alexander Fleming Laboratory Museum (Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust)

It can be said that one of the most significant scientific discoveries of the 20th century was the double helix structure of the DNA molecule proposed by James Dewey WATSON and Francis CRICK in 1953. Following the discovery, advances such as gene duplication and transcription were made in related research. In tandem with progresses in digital and biological technologies, artists like George GESSERT, Joe DAVIS, Larry MILLER, and Stelarc participated in specialized scientific studies and created artworks from the 1980s onwards. Over time, more and more artists began to incorporate genetic engineering, tissue culture, or synthetic biology into their art practices, resulting in scientific tools as artistic expressions becoming widely accepted. Joe DAVIS, a pioneer in the field of BioArt in the United States, collaborated with molecular geneticist Dana BOYD at Harvard University to insert a coded visual icon into the DNA sequence of a bacterial strain, E. coli. The piece, Microvenus, is the first artwork created with techniques of molecular biology.

It was not until in 1997 artist Eduardo KAC coined the term “bio art” in his performance work, Time Capsule, that theorists and critics started to use it to refer to art practices in which artists work with “live tissues, bacteria, living organisms, and life processes.” The year of 1997 thus can be seen as a watershed that defined the pre-BioArt period and the early development of BioArt. In the book, Signs of Life: Bio Art and Beyond, KAC explained:

Bio art is a new direction in contemporary art that manipulates the processes of life. Invariably, bio art employs one or more of the following approaches:

(1) The coaching of biomaterials into specific inert shapes or behaviors;

(2) the unusual or subversive use of biotech tools and processes;

(3) the invention or transformation of living organisms with or without social or environmental integration.5

KAC’s creative career began in the 1980s. At a time when the Internet hasn’t been made widely available across the globe, he was already working on telecommunication art, telepresence art, and the like. His artistic practice centered on experimental poetry, experimental writing, and visual art; he also attempted to develop new poetic languages and display new poetic possibilities through video art, hologram, computer program, and Internet art. With scientific development in genetic duplication, chimera, and genetically modified organisms, KAC started to use biomaterial as a tool in his exploration of artistic mediums. In the book Media Poetry: An International Anthology, he put forward the concept of “Biopoetry,” and defined it as a group of writing practices that contained at least 20 genres, including Atomic writing, Transgenic poetry, Amoebal scripting, Dynamic biochromatic composition, Bacterial poetics, Tissuetext, and so forth.6

The exploration on boundaries and interrelations among humankind, animals, and machines has long been a focus in KAC’s artistic creation. In the site-specific work Time Capsule, he turned this exploration towards his self. With the subcutaneous insertion of a microchip, the work took place simultaneously in his own physical body and a remote database, while being broadcast on television and on the Internet. On being scanned, the microchip (an identification transponder tag) generated a low energy radio signal that energized the microchip to transmit its unique and inalterable numerical code shown on the scanner’s display. After the implantation procedure, a small layer of connective tissues would form around the microchip, anchoring it in place. Through live transmissions of this experiment on television and online, KAC also intended to highlight the “connective tissues” of the World Wide Web, suggesting our skin was no longer the protective boundary that demarcated the human body.

In 1998, based on STEICHEN’s and GESSERT’s works of plant crossbreeding, KAC coined another term “transgenic art.” In an eponymous essay, he proposed certain manifesto-like ideas7 to address possibilities and diverse facets of the “contemporary” BioArt:

In this essay, in addition to the seeming eloquence of his artistic strategies, KAC also mentioned his ongoing research on green fluorescent protein (GFP). Later, in 2000, he presented GFP Bunny – a genetically modified rabbit that glowed green when illuminated with blue light, owing to its carrying the protein, which was originally found in a certain species of jellyfish.

After KAC published his work of transgenic art, he was commissioned by the Ars Electronica Festival 1999 in Linz to create Genesis, a work addressing the intricate interrelations of biology, belief systems, information technology, ethics, and the Internet. The artist translated a biblical statement – “Let man have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moves upon the earth” – into Morse code, and then converted the code into base pairs according to a conversion principle specially developed for this work. This sentence was chosen for its implications regarding the dubious notion of humanity’s supremacy over nature.

Since then, BioArt practices became more and more common in art and academic institutions. Artists Oron CATTS and Ionat ZURR launched the “Tissue Culture and Art Project” in 1996, which led to the establishment of SymbioticA at the University of Western Australia in 2000. SymbioticA is a synthetic biology research institute which allows artists and scientists alike to engage in research, learning, critique, and hands-on practices relevant to life sciences. Other institutions, such as Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, the Arts and Genomics Center at Leiden University, the Finnish Bioart Society, the Bio Art Lab at the School of Visual Arts, New York, the University of Edinburgh, and Stanford University, have also committed resources to cross-disciplinary research on collaboration between life sciences and art .8

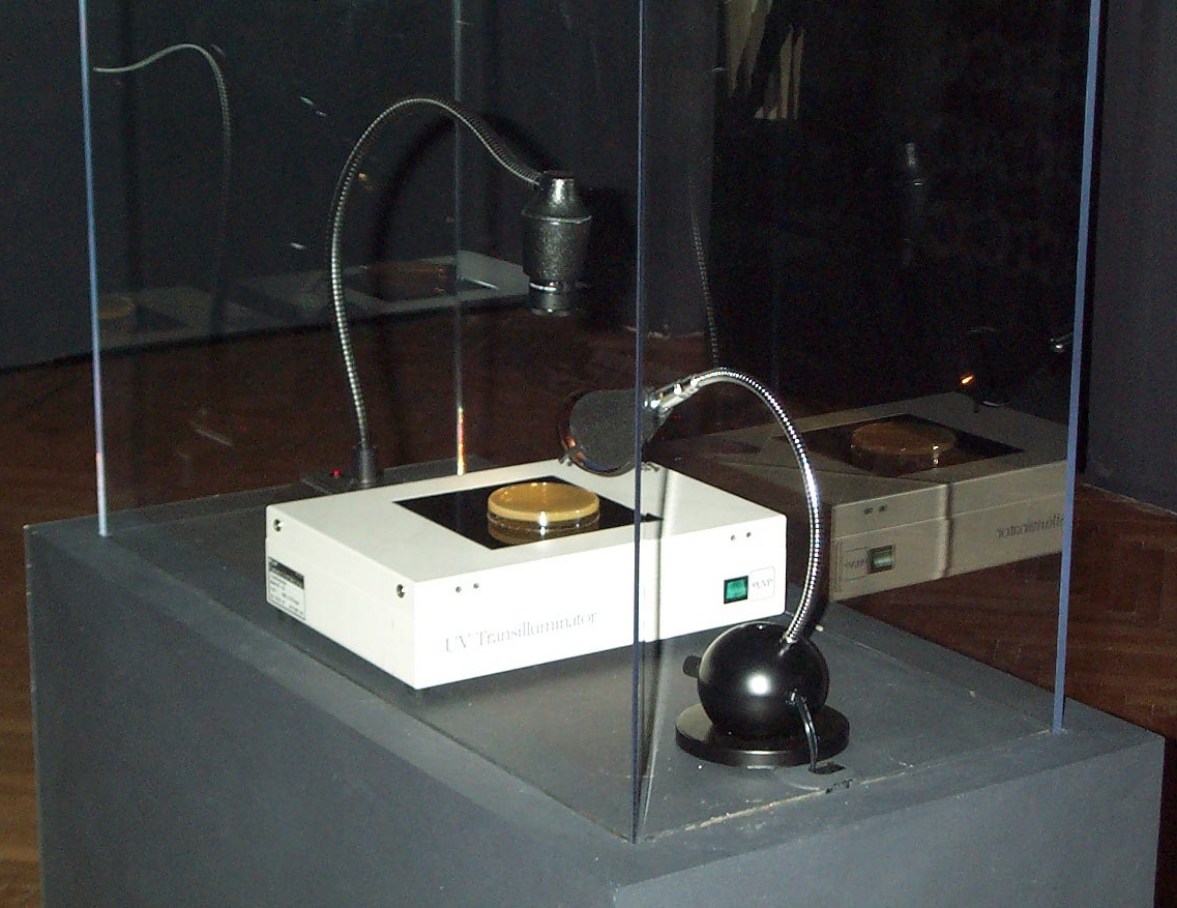

Eduardo KAC was commissioned by the Ars Electronica Festival in 1999 to create Genesis. Photo courtesy of Dave PAPE (public domain)

Eduardo KAC was commissioned by the Ars Electronica Festival in 1999 to create Genesis. Photo courtesy of Dave PAPE (public domain)

With a rapidly increasing amount of attention paid to BioArt by various institutions, awards, and research grants, BioArt ascended to prominence as one of the most sought-after fields in artmaking and research. The rise of biotechnology also prompted laboratories and research institutes that were keenly attuned to world trends to seek out artistic collaborators. As a result, BioArt gradually evolved from the experimental explorations of artistic mediums and methodologies since the 1920s into a fashionable buzzword on our contemporary art scene. Media studies scholar Jens HAUSER offers two possible factors that might have contributed to this phenomenon:

While on the one hand, the ascent of biology as a leading scientific field has led to an inflation of biological metaphors within the humanities, on the other hand biotechnological methods provide artists not only with the topics but above all with new means of expression.9

As the long-dominant influence of genetic art dwindled, the horizon and creative vision of BioArt seem to be opening up with the inclusion of tissue culture, neurophysiology, synthesis of artificial DNA sequences, as well as visualization of biotechnology, medical experiments, and molecular biology, etc. in the dialogue.

In 2017, exactly 20 years after the term “bio art” appeared for the first time, KAC and George GESSERT, Marion LAVAL-JEANTET, Benoît MANGIN, Marta de MENEZES, Paul VANOUSE published a manifesto to explicate the term again:10

What Bio Art Is: A Manifesto

•Bio Art is art that literally works in the continuum of biomateriality, from DNA, proteins, and cells to full organisms. Bio Art manipulates, modifies or creates life and living processes.

•In manipulating biological processes, Bio Art intervenes directly in the networks of the living.

•Life has a material specificity that is not reducible to other media.

•Without direct biological intervention, art made solely of acrylics, paper, pixels, plastic, steel, or any other kind of nonliving matter is not Bio Art.

•All art materials have ethical implications, but they are most pressing when the media are alive. We advocate for an ethical Bio Art: ethical with respect to humans and nonhumans.

•Some bioartists use living media to express human concerns, while other bioartists celebrate nonhuman organisms and our connections with them.

•Bio Art has no obligation to thematize topics that relate to biology or the living.

•We trust art audiences to recognize that because Bio Art is alive, all Bio Art has political, social, cultural, and ethical implications, whether or not these are made explicit by the artist.

•Bio Art challenges the boundaries between the human and the nonhuman, the living and the nonliving, the natural and the artificial.

•This manifesto recapitulates and restates issues addressed in our work from the beginning.

Although this manifesto seems to imply certain orthodoxy of theirs in the field of BioArt, we should recognize that BioArt is still a developing field, one which continues to question and challenge society, philosophy, and ethics, worthy of our attention and participation. To wrap up, HAUSER quotes the pioneering bioartist Joe DAVIS’s surprising remark as a useful point of departure: “Some day, it will no longer be called bio art, but rather simply: art.” 11