The annual meeting of the Conferences of Parties (COP) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is the world’s premier summit on global climate action. More than a theater of diplomacy, the semi-official side events of speeches, conferences, and exhibitions are also important opportunities for representatives of states, international organizations, research units, and advocacy groups to engage in lobbying and communications in areas of urban climate action, communal experiences, and indigenous rights. However, during COP26 in 2021, a side event called “Arts & Science: The new inspiration couple?” adopted the documentary style as an example for arts and cultural workers to invoke the power of storytelling, making climate science more approachable and mobilizing the masses to practice climate actions.

Experts and scholars have devised all manners of carbon-neutralizing technologies, but it’s up to the general public to put them into practice. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in the Working Group III (WG3) of its IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change, indicates that if society is willing to make changes in the socio-cultural aspects, construct low-carbon infrastructure and adopt low-carbon product technologies, global greenhouse gas emissions will be reduced by 40 to 70% by 2050. Based on this projection, the effectiveness of changing social behavior is no less significant than developing new and unproven hydrogenic energy or carbon-capturing technologies. Thus, the green-collar workers’ proposed alliance with artists wasn’t by chance, but born of necessity.

Bruno LATOUR’s book Face Á Gaïa: Huit conférences sur le nouveau régime climatique used the contrasting perspectives of “nature/culture” to recount the history of green-collar workers’ solicitation for alliances: the scientific community had reached a consensus on climate change back in the 1990s, but unlike other areas of scientific research, the narrative of climate change is not neutral, but accusatory. In other words, portraying human activity as the prime factor in climate change amounts to a moral critique of high-emitting industries, so that science becomes entwined with politics. Conversely, detractors appropriate the “scientific uncertainty” of theories and accuse scientists of stigmatizing the high-carbon emission industries with unsubstantiated “evidence” and becoming climate change zealots. The situation calls upon scientists to step out of their ivory towers and look for support within the public sphere. From academia to NGOs, scientists gradually enter the mainstream political agenda, to culminate in the global United Nations-based system of governance as described at the start of this article. Since the alliance had brought scientists out of their echo chambers, communications techniques must also evolve. Thus, “storytelling” has become a skill of urgency for green-collar workers, with arts and culture groups becoming potential allies.

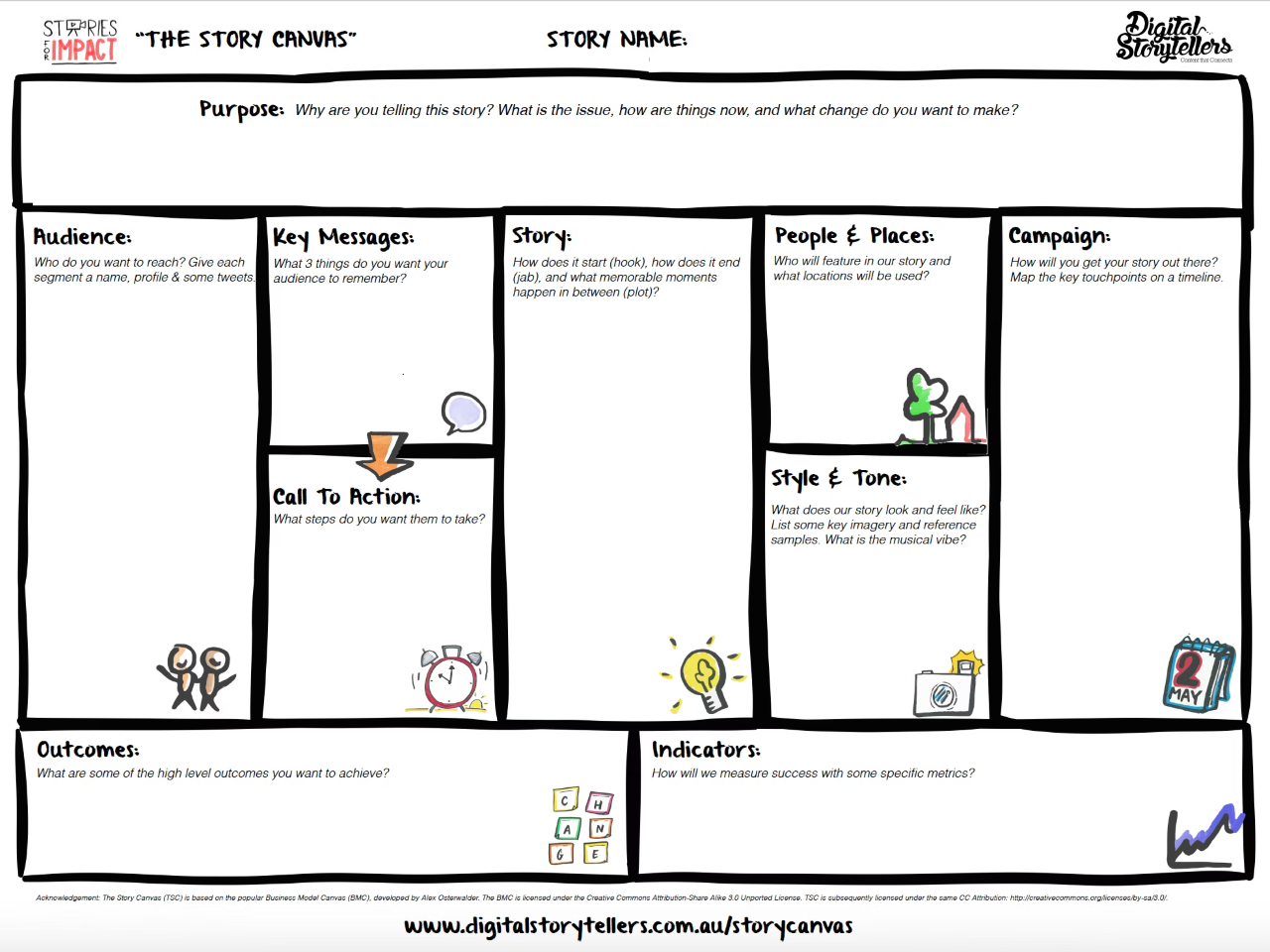

In the past few years, international convention bodies have adopted “storytelling” as an important tool for climate action. In 2018, the Technical Support Unit (TSU) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Working Group I (WG1) commissioned the international organization Climate Outreach to produce Principles for effective communication and public engagement on climate change, to guide members to turn raw data into compelling stories. During COP25 in 2019, there were also four “Climate Storytellers” workshop sessions which used the “Story Canvas” template to write down convincing stories in the promotion of climate action. At COP26 in 2021, at the “Arts & Science: The new inspiration couple?” series of events, the convention collaborated with the artistic action platform ReGenesis launched by the official partner, Israeli artist Michel PLATNIC, in the exhibition Echoes of the Future focusing on the two global initiatives of “Race to Zero” and “Race to Resilience.” Showcasing eight pieces of art, the exhibition outlines a vision of a net-zero and resilient future, offering hope for audiences and forming a base of support for diplomats and scientists at the conference.

But in such a setting, art is often reduced to an educational and promotional tool for green collar workers. In the example of the “Story Canvas,” the infographic was appropriated from Alex OSTERWALDER’s original template intended for commercial use. The “climate story” serves as the “business model,” while the value proposition has been replaced with a sense of climate crisis, and the goal changed from profitability to encouraging climate action. “Channels” and “target audiences” have also been replaced with subdued terms of advocacy methods and recipients. As for the creative process and aesthetic or conceptual values of the works, they’re not a main concern of the workshop. In the case of the Echoes of the Future exhibition, artists were asked to not depict climate catastrophe, crisis, or negative emotions, but to emphasize the aura of a bright and net-zero resilient future.

The “Story Canvas” provides users with a template to write down persuasive arguments of advocacy. The worksheet shown above is the master template. Image © Digital Storytellers

The “Story Canvas” provides users with a template to write down persuasive arguments of advocacy. The worksheet shown above is the master template. Image © Digital Storytellers

Such requests are not new to climate activists: NGO communities for advocacy often appropriate tools from start-up or design communities to deliberate or manage issues. As for the restrictions on creative processes in practice, it occurs throughout the climate activists’ long-term involvement with the public. For example, in the Principles for effective communication and public engagement on climate change, the Climate Visuals principles on communicating climate change offer the following recommendation: “Tell new stories: Familiar, ‘classic’ images—polar bears, smoke stacks, deforestation—can prompt cynicism and fatigue. Less familiar (and more thought-provoking) images can help tell a new story about climate change.” But for arts and culture workers intent on addressing real issues, is their art obligated to take on such onerous limitations and responsibilities? Alternatively, is there a possibility for art to take a proactive stance, participating in scientific research, spearheading policymaking, specifying the mode of collaboration, or even playing the role of the opposition to criticize governing bodies and advocates?

Talk of climate change and art in Taiwan inevitably brings mention of Art as Environment—A Cultural Action on Tropic of Cancer in Chiayi, and other environmental art action which sprung up across the island. Unlike the top-down, solutions-based, and locally adapted actions, the main goal in the field of environmental art actions is not climate change advocacy, but rather to draw consensus as a community and work towards collective action. In the words of Julie CHOU1, in her book Beyond Dialogue: A Journey of Transforming Place through Climate Change, art in this sense largely follows the context of public art, which emphasizes cooperation and dialog. The subject of collaborative dialog not only includes local communities, but also the history, the place, and even the indigenous flora and fauna.

Throughout the project, actions are the creator’s response or resistance to art history, a critical value statement. The value of a work lies not only in its concept or form, but also in its ability to incite change. Take for example A Dialogue with Oysters: The Art of Facilitation in Budai Township, Chiayi County. The artist’s conversation with human and non-human actors gradually reveals the relationship between local producers and society at large. UK-based artist David HALEY and his team then direct their response to topics of negative impact such as discarded oyster shells, land subsidence, and sand bar erosion, collaborating with experts and residents to initiate action, such as using oyster shells as the pavement layer for water reservoirs towards carbon sequestration, turning abandoned salt farms into environmental education classrooms, or stacking oyster shells to protect the shoreline. This also makes environmental art action unsuited to the frameworks of exhibitions, compared to conventional objected-based works. Instead, these must be presented in the format of reports to satisfy the conditions of subsidies and grants (a point which LU Pei-Yi thoroughly examined in the article “Art as Environment—A Cultural Action on the Plum Tree Stream”2).

The above discussion takes on the position of the artist. If other communities are to be taken into account or the social impact assessed, it must involve other stakeholders, multi-disciplinary concerns, or even criticism from outside circles. For example, can the artist vouch for the oyster installation’s effectiveness in preventing floods in A Dialogue with Oysters: The Art of Facilitation? Or what are the liabilities of the artist in the event of defects in the art installation leading to property damage? However harsh these questions may be, they illustrate the greater challenges of artistic environmental action when confronting the real world. After all, the aim of the arts and culture community is not to respond to climate change on the conceptual level, but to prevent the calamities brought about by climate change.

The complexity of climate change makes adapting “actions” into reality an even greater challenge. Green-collar workers categorize strategies into two major domains of mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation means statistically lowering the content of man-made greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, such as reducing emissions or sequestration. Adaptation is to make changes to minimize the impact of climate change. Since environmental action art happens at the sensory scale of communities, it mainly falls under the domain of adaptation, primarily corresponding to activities with a lower technical threshold such as climate education, afforestation and beautification, and environmental protection. In contrast, actions toward mitigation face a higher technical barrier or even greater risks in practice.

Take for example the controversial Arts of Coming Down to Earth project at the 2020 Taipei Biennial—You and I Don’t Live on the Same Planet: the artistic action entailed calculating the greenhouse gas emissions for the duration of the biennial, followed by clearcutting of a forest in the Daluntou area to serve as reforestation grounds—in an artistic act of carbon sequestration under the guidance of Geotechnical Engineering Office of Taipei City Government. But due to lapses in the process, it became known as the “Daluntwei forest-clearing incident”3 among environmental groups. Perhaps in the artists’ consciousness, they had performed due diligence on the project, consulting numerous experts in academy and delegating the actual clearing of the forest to government departments and the professionals. Yet issues of forest carbon sequestration go beyond forestry, extending to areas of conservation, governance, and community, with divergent viewpoints of experts from various backgrounds (as seen in the recent Datan algal reef LPG infrastructure disputes), which cannot be resolved with short-term interdisciplinary discussions. This debate also highlights another challenge for artistic intervention in matters of climate change: the difficulty of demonstrating long-term benefits. Aside from the harms inflicted on the environment, a good forest carbon sequestration project must follow a Measurable, Reportable, and Verifiable (MRV) process. In other words, artists must measure the amount of greenhouse gases absorbed by the forest each year, release status reports on a regular basis, and have these reports certified by a third party.

In-depth understanding of issues, multilateral exchange, understanding different positions, and establishing a mechanism of MRV for accountability…. These multi-layered processes are what society expects of climate action today. Whether it’s governments, corporations, or artists, all face scrutiny in actions related to climate change. Such taxing processes clearly exceed what creators can manage. Yet without them, the effectiveness of climate action art is hard to ascertain. Of course, the creators can maintain that the value of climate action art lies in creating dialog and dialectical thinking rather than actual prevention of climate disasters, but doesn’t this play to outside claims of art being merely “storytelling”? Also, how does art differentiate itself from other professional practices of regional development such as regional revitalization, design, or architecture (such as Assemble, winner of the 2015 Turner Art Award)?

What should be pointed out is that the above predicament is not exclusive to artistic action, but rather long-standing global governance issues in areas such as climate change and public health: the topics rely on a bottom-up approach from regional action to the centralized. Yet regional actions do not conform to the frameworks of centralized assessment, resulting in the inability of the central government to understand regional development needs and an awkward perception of bureaucracy in the central government among regional actors. The current subsidies-based system in Taiwan within regional adaptation policies face similar challenges.

If the methods of NGOs, environmental activists, writers, and ecologists in the 2018 Taipei Biennial—Post-Nature: A Museum as an Ecosystem reflect Mali WU’s and Francesco MANACORDA’s long career in the art of social engagement, then the 2020 Taipei Biennial—You and I Don’t Live on the Same Planet represents another aspect of art’s response to the climate crisis: to examine how human values have harmed the welfare of all things on Earth, ultimately leading to ecological crisis.

The academic world’s reflection on human values started in the latter part of the last century, through the works of scholars such as Bruno LATOUR, Peter SLOTERDIJK, Gilles DELEUZE, Jane BENNETT, and others, who attempt to revisit metaphysics and ontology, reexamining the relationships between humans and non-humans. For artists with a long-term interest in social sciences, creating art in response to these philosophies isn’t a new undertaking. YANG Cheng-Han’s article “The Three Stages of Anthropocene in Taiwan”4 has shown in detail the trajectory of thought in Taiwanese art circles since 2008, which reflects not the anxiety of artists towards climate change, but rather how international thought entered local artistic circles and crossed with contemporary art through artists’ projection towards local issues. With the rise of climate change awareness, terms such as Anthropocene and Gaia have become popular in associated literature, while “human geography,” “science, technology, society (STS),” and “environmental politics” have entered the consciousness of the public.

Whether it’s the prophesizing of dissociation between perception and action in the writings of YANG Cheng-Han prior to the 2020 Taipei Biennial, or criticisms of “spatialization of LATOUR’s discourse,” the inability to be “Down to Earth,” and “commentary which lacks political agency” by KAO Chien-Hui, KAO Jun-Honn, and CHU Feng-Yi in response to the exhibition, what’s obvious is the disconnect between the response and locale. During the exhibition, I interviewed members of the Taiwan Youth Climate Coalition, learning about their experiences of viewing the exhibition, participating in the Theater of Negotiations, or volunteering in the exhibition, which provided another angle in the discussion of the disconnect: what they found most memorable were works in the section of Planet Terrestrial, in which elements of climate change can be easily experienced visually. Regarding the works of Territorial Agency, which showcase global oceanic change, and Frame of Reference I & II, which present the geological changes in Taroko Gorge, members of the Taiwan Youth Climate Coalition expressed their thoughts of “being glad to see climate change topics at the art museum, to have it brought out of its echo chamber.” Conversely, works which do not prominently feature the visual elements of climate change, those that respond on a conceptual level, were deemed too abstract. Besides being unintelligible, it’s hard to imagine them having any effect on climate change.

Exhibition view of Territorial Agency’s Oceans in Transformation (2020). The work was originally commissioned by TBA21–Academy. This adaptation was co-produced by Taipei Biennial 2020 and ZKM Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe. Photo courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Exhibition view of Territorial Agency’s Oceans in Transformation (2020). The work was originally commissioned by TBA21–Academy. This adaptation was co-produced by Taipei Biennial 2020 and ZKM Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe. Photo courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Exhibition view of SU Yu Hsin’s Frame of Reference I & II (2020). Photo courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Exhibition view of SU Yu Hsin’s Frame of Reference I & II (2020). Photo courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum

The disconnect pointed out in the above criticism is not resulted from the curators’ or artists’ strategy, but the way in which they view academic theory. In research of social sciences, discussions of metaphysics and ontology often serve as a review of existing literature or research method, a strategy to help the researcher find a corresponding research question. The research question is based on the researcher’s private experience, a question raised about the real world. In other words, although theories mostly originate from the work of western researchers, if we see theories as a tool rather than the research goal, using local issues as the research problem, we can still conduct locally relevant research. In the example of Arts of Coming Down to Earth, tracking the carbon footprint of the venue and steering cultural institutions towards sustainability are a commendable aspect of the project. The project also exemplifies the premise: a vision of returning to nature, allowing art museums to go beyond the custodianship of human artifacts, but also non-human communities. But if curators and artists are willing to use discourse as a weapon and boldly subject experts, public offices, and all manners of carbon sequestration to its criticism, maybe they’ll uncover the ideologies behind the measures of “cutting down trees to reduce carbon” and “active management” including post-colonialism, human-centrism, and technological optimism, which Anna Lowenhaupt TSING has written at length about in the book Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. From this point of view, can we claim that artists and curators unwittingly placed an anti-LATOUR and anti-DELEUZE artistic action within the context of a Latourian exhibition?

Global climate action is in full bloom, so now is the time for deeper reflection. Take for example Jeffrey SACHS’ winning of the Tang Prize.5 SACHS encourages the world to put down differences and work collectively in climate change projects, winning him acclaim among the world’s green-collar workers. We can look at it at a symbolic level, visualizing SACHS’ proposition, adopting his vocabulary in writing the exhibition’s discourse, connecting to other theories, and producing a space both aesthetically pleasing and conceptually imaginative, in works that respond to climate change conceptually. But if we see SACHS’ proposition as a tool, incorporating local viewpoints and personal experiences for criticism, then we can discover that SACHS’ proposition against “dissent” is a call for Europe and America to stop focusing on Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Xinjiang human rights issues, and work with China on climate change first and foremost.6 But ironically, funding for the Tang Prize and its panel of judges all come from Taiwan. This rift illustrates the risk of responding to abstract academic concepts in the absence of deeper understanding and local perspectives. Responding on a conceptual level to climate change isn’t untenable, but it should be more profound, bold, concrete, and political to be able to engage locally.

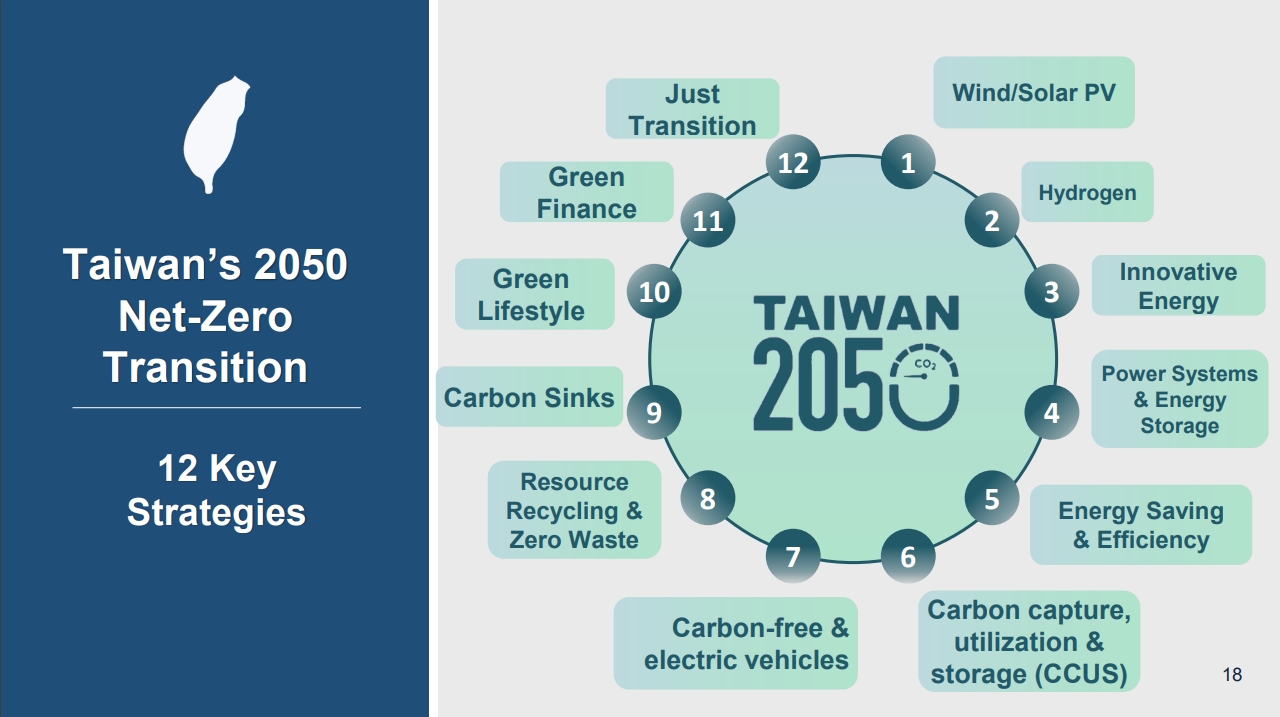

To prevent a global temperature rise of 1.5°C by the end of the century, many countries have set the goal of “Net Zero Emissions by 2050,”7 with a series of hard-to-pronounce policies, such as “reducing emissions in 2030 by 78% compared to 1990 levels” and “achieving 100% all-electric vehicle sales by 2040.” These numbers affect the pace of carbon reduction and economic development, becoming topics of contention. But whether in the government or private sectors, there is difficulty in turning goals into visions of future lifestyles to initiate public discussion.

For the public,an inability to imagine what life will look like in the future means it’s hard to assess the critical impact of policies, which lowers people’s desire to participate. Take “just transition” for example, which focuses on the negative social, environmental, and economic effects brought by the economic reform. Although we understand the impact on the auto industry by a “100% all-electric vehicle sales by 2040” policy, labor groups are more accustomed to discussing wage reductions, layoffs, occupational hazards, and other everyday issues. It’s hard to ask them to review policy papers and speculate on future labor conditions. On the other hand, industry groups with cultural capital can more easily intervene in the early stages, representing the position of companies and establishing policies to their advantage. The difficulty of envisioning future living conditions also makes it hard for the public to call out the underlying ideologies within policies. Take the example of the UK’s Green Recovery Challenge Fund, which aims to plant a million trees nationwide by 2050. Do we really have the chance to fully discuss the existing concept of “Ius in re,” or right in property, and with the help of technology, cite the concepts of Théâtre des négociations, Council of All Beings, and The Parliament of Things to establish a new partnership of equality between trees and humans?

In recent years, more and more authorities of climate change have begun to collaborate with “artists” to help visualize the future. (They probably couldn’t tell the differences among graphics styles, contemporary art curation, integrated design companies, and commercial design agency groups though.) For example, UK’s Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy uses the official energy statistics database as a basis for the interactive game “My 2050 Calculator,” which allows the public to visualize relationships between the energy mix and policy goals. In 2018, NTU’s Graduate Institute of Journalism, working with Science Media Center Taiwan, created the Sea-made Wind Generator Interactive News Exhibition, using VR technologies to simulate off-shore wind farms. In the private sector, the Taiwan Youth Climate Coalition was inspired in 2019 by Mali WU’s Tomorrow as a Lake Again to create the picture postcard project Imagining Taiwan Under Water, inviting young volunteers to imagine a future of climate change apocalypse, depicting the surviving scenic spots of Taiwan on travel postcards. But in this example, the alliance between green-collar workers and storytellers is not perfect. For instance, in Imagining Taiwan Under Water, there is a depiction of tourists on rubber rafts enjoying street food in a flooded Shilin Night Market. Though the imagery draws attention to climate change impact, it’s light on climate science, since by estimate of current models, the Shilin area is unlikely to be submerged in water. The food stalls and transportation technologies are also a hash of existing technologies (such as car lights mounted on a floating raft), oblivious to emerging technologies. Otherwise, even if the public can create animated images of the future in “My 2050 Calculator,” complete with decentralized power grids, photovoltaic cells, and hydrogen fuel cells, we still cannot fathom the net-zero future, as well as the sentiments, desires, prejudices, and other emotional factors. These emotional factors are in fact key to the public’s acceptance of just transition.

Exhibition view of Mali WU’s Tomorrow as a Lake Again (2008). Photo courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Exhibition view of Mali WU’s Tomorrow as a Lake Again (2008). Photo courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Taiwan Youth Climate Coalition’s travel postcard Imagining Taiwan Under Water. Illustration © Taiwan Youth Climate Coalition

Taiwan Youth Climate Coalition’s travel postcard Imagining Taiwan Under Water. Illustration © Taiwan Youth Climate Coalition

The tendency of seeing arts and culture workers as “storytellers” among Green-collar workers reflects flaws in existing climate action, and is not what arts and culture workers expect to achieve through their work. Contemporary art’s way of responding conceptually and through artistic action also does not meet the green-collar workers’ expectations of “solving rather than responding to the issue.” Neither is a collaborative model which brings out the strengths of both groups and mutually beneficial. The communications challenge of climate issues we currently face not only stems from “an inability to tell stories,” but the lack of local communications mechanisms, an overly abstract policy goal, an inability to translate technological developments into lifestyle changes, and the failure to appeal to emotion. The inability of the public to address the heart of the matter critically in climate policies is similar to the predicament of the arts and culture workers as mentioned above, where a conceptual response to climate change fails to connect locally. Perhaps the arts and culture workers can break through the impasse by leveraging their expertise, relating, criticizing, resorting to personal experience, and transforming concepts into physical experiences.

In the end, though arts and culture workers should bear part of the burden of climate change as fellow human beings, I do not believe art has an obligation to respond to climate change. Should arts and culture workers wish to address climate change of their own accord, the most direct and effective way is to refer to the guide published by UK non-profit organization Julie’s Bicycle, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions during the production of art. If institutions just raise the temperature settings of their air conditioners by one degree Celsius or print fewer brochures, it will definitely do more than another round of discussion on Gaia or Anthropocene.