2017年12月25日,我抵達克羅埃西亞首都札格瑞布的當代藝術館(The Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb),我將在這裡駐村三個月,而餘下來的冬季假期都只有我和留守的警衛一起度過。我是受札格瑞布獨立文化及青年中心(POGON – Zagreb Center for Independent Culture and Youth,簡稱POGON)主辦的藝術家駐村計畫邀請而來的。2017年,我在德國的斯圖加特的孤獨城堡基金會(Akademie Schloss Solitude)度過了八個月,而這項駐村計畫是該基金會和札格瑞布獨立文化及青年中心交流計畫。

我沒料到的是,冬季並非造訪札格瑞布的最佳季節。冬眠的氣息瀰漫在假期中半空不滿的街道。對許多人或甚至對當地人而言,寒冷的天候都是讓人情緒低落與不喜好社交的原因。後來我才發現,整個克羅埃西亞的人口大約四百萬人,其中有一百萬人住在札格瑞布,而且這個數字正在逐步下降。我在這裡遇到的每個人,近年來都有親友離開克羅埃西亞,且各行各業的人都有。我開始猜想,我感受的沉悶氛圍,是否僅僅源於天候,或者背後還有更複雜的原因。

駐村的頭一個月,POGON的資深經理Sonja Soldo非常努力地幫我介紹藝術館的工作同仁以及這個圈子的朋友,但是進展不大。第一次和藝文圈的人碰面時,大家試著向我解釋為何我會遭遇如此低沉的氛圍。每個人講的故事大同小異:右翼政府行事保守,大幅削減預算,縮小公共空間,因此扼殺了國內的文化活動。大家異口同聲,克羅埃西亞文化發展的黃金時期已經過去了,那是2000年的初期,即是圖季曼(Tudjman)的專制政權剛剛倒台之際。大家談起這些事情,頗有一種嚴陣以待暴風將至的情緒。

克羅埃西亞首都札格瑞布的當代藝術館(The Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb),建築是一個玻璃盒子。圖/鄭德恩提供

克羅埃西亞首都札格瑞布的當代藝術館(The Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb),建築是一個玻璃盒子。圖/鄭德恩提供

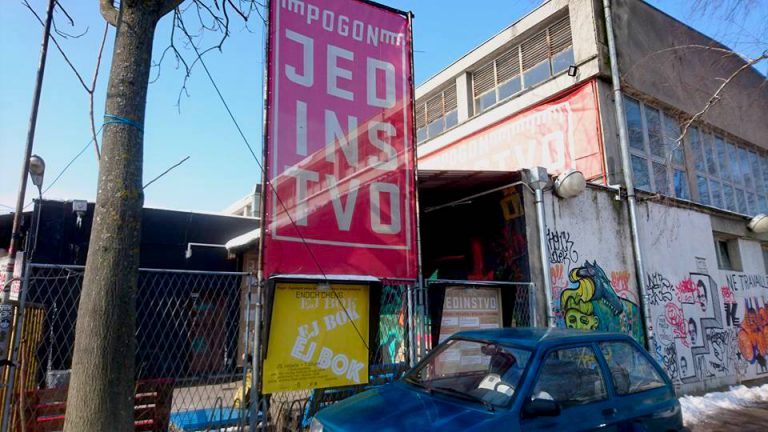

POGON經營的賈丁斯提弗工廠(Jedinstvo Factory)未來將改造成一個複合功能的文化中心。圖/鄭德恩提供

POGON經營的賈丁斯提弗工廠(Jedinstvo Factory)未來將改造成一個複合功能的文化中心。圖/鄭德恩提供

後來Soldo介紹我認識了當代藝術館的圖書館員兼策展人Jasna Jaksic,她答應帶我參觀當代藝術館,在參觀的過程中,她簡要地介紹了這個國家於社會主義中發展的藝術史,從過去的南斯拉夫一直講到今日的克羅埃西亞。

我留意到一個重點,自1960年代起,克羅埃西亞便已開始某種前衛的發展模式,其中脫穎而出的要屬著名的「新潮流」(New Tendencies)與活躍的行為藝術領域。像是Goran Trbuljak這樣的代表人物,便在1970年代以海報的創作形式予人留下深刻的印象。他在當年還是當代藝廊(Gallery of Contemporary Art)的當代藝術館中舉辦個展,其中海報名為「事實上,一個人得到一個展覽的機會比展覽的內容還來得重要。」(The fact that somebody is given the opportunity to make an exhibition is more important than what is shown at that exhibition.)。作為一名藝術家,能在藝術館裡駐村,無疑是非常夢幻;然而,這樣的優勢同時也讓我不得不問:在一個更大的文化結構中,作為一名藝術家究竟意味著什麼?或者,將Trbuljak的觀點推得更遠一點:「藝術與藝術家究竟可以在什麼樣的環境與條件下運作?」

當代藝術館的建築是一個玻璃盒子。當我跟著Jaksic巡檢這間2009年開館至今的機構,發現各處的濕度與溫度波動很大,這對於館裡的作品而言其實不算理想。另外,雖然館方展出許多當代藝術史上的精彩作品,但大部分時間館內的參觀人數並不多。我對Jaksic說,如果沒有她的導覽,一個外國人很難認識當地的藝術發展。她同意且補充道,即使對當地人而言,這也不是件容易的事,更令人沮喪的是,就算是當地的藝術史學生也不見得有參觀藝術館的習慣。要批評當代藝術館沒有盡到推廣藝術的責任並不困難,但是我在見過包括克羅埃西亞各地的博物館界人士後,我了解這個現象並非札格瑞布獨有。

我開始明白,藝術機構是文化生態整體結構的一部分,其可能性取決於各方因素織就而成的複雜網絡,其中包括:制定硬體、建築、財務與政策結構的政府與計畫主事者;負責主持、籌劃博物館與藝術館所有運作、活動和宣傳策略的團隊;還有公共利益以及在專業領域發揮作用的人士――這些也是世界各地藝術機構所需面對的議題。

札格瑞布當代藝術館內有件作品令我印象深刻,因為它提供了一個視角,讓人得以觀看這些盤根錯節的議題。這是由克羅埃西亞已故女演員和藝術家Jagoda Kaloper創作的《鏡看》(Behind the Looking Glass)。這件作品中,藝術家拍攝自己在鏡子、玻璃窗面或水坑裡的倒影,將其穿插在她自1960至2010年參演的南斯拉夫電影檔案片段當中,新創作的影片和電影檔案的影片交錯,藝術家的鏡頭也隨之推移,同樣地,反之亦然。

我沒有任何南斯拉夫電影的背景知識,我也不認識這位藝術家,但是這件作品讓身為觀眾的我,得以意識到自己的觀看,以及觀看的位置。我時而在舊日電影裡透過攝影師的眼睛觀看,時而採取女性藝術家的目光,不僅向內凝視自我的映射,也在一部部老電影的不同時空間轉換,思考一個更為廣闊的歷史脈絡。在此作品中,藝術家成功示範了個體如何同時看待宏觀與微觀的議題,因為我們既在內,又在外;既屬於過去,也屬於現在。 重要的是,我們是否能夠審時度勢,隨機應變,即時調整自己的角色。

一位策展人回想起她與Kaloper合作的過程,Kaloper曾提及她遇過一些美國好萊塢的女演員在退休後的際遇都很悲慘,讓她感到很震驚,因為在南斯拉夫的體制下,國家會提供退休金照顧像她這樣退休的演員。即便這個體制如今已被新自由主義的思維所粉碎,但我覺得這不應該被忘記,甚至我們應該向這個制度學習,去考慮藝術家是否有可能被納入一個更大的福利結構,並成為公民社會發展的其中一環。

2005年的札格瑞布,「在地方選舉的幾個月前,一個聯盟應運而生,第一次有機會針對獨立文化與青年力量的需求清楚表達、公開討論,並在未來決策者所簽署的文件中發表聲明。」1負責我此次駐村的 POGON,便是這個由公民社會所主動爭取的結果,其宗旨為「提供硬體設施,讓札格瑞布的機構得以免費使用,進行各項文化節目與青年活動」2,成為一個沒有美學限制的開放平台。

經過多年的爭取、抗議與佔地使用,POGON現在除了自己的辦公空間外,還負責經營賈丁斯提弗工廠(Jedinstvo Factory)。我對這個空間非常感興趣,因為在香港不容易找到像這樣巨大「黑盒子」般的空間。當Soldo告訴我,未來這個空間會改造成一個複合功能的文化中心時,更加深我的好奇。我們在香港為了建設一個文化區域,已經討論了十多年,所以聽到克羅埃西亞的文化規畫時,我怎麼能不被吸引?又難免會想提問,這個未來的場館服務的對象是誰?誰是這裡未來的藝術家?誰又是未來的觀眾?

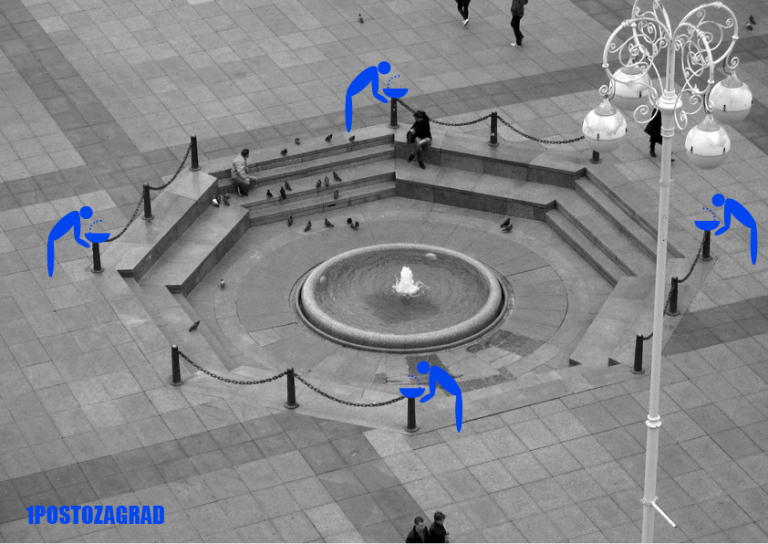

駐村期間過了一半,我與當地文化圈的聯繫仍然不多,大部分的人沒有什麼反應,Soldo(以及後來交到的一些新朋友)一再向我保證,他們自己也覺得在當地很難交流。不知怎的,我覺得我好像走錯了方向。我後來從當地的行動分子Sasa Simpraga那裡學到,也許該從一些異於平常的地方著手,可能更容易引起共鳴。Simpraga創立了詩歌節「五十首雪之詩」(50 Poems for Snow),訂在降雪的第一天在札格瑞布的公共空間舉行,後來又擴展到克羅埃西亞的其他城市,以及歐洲多國。他把詩歌放在公共長椅上,以鮮為人知的重要人物為街道命名,並且提倡並重建過去提供大眾飲水的公共噴泉。他大多從小型的行動出發,需要持之以恆才能令人有感,但卻留下了蛛絲馬跡,讓公眾找到自己與他們所居的城市及其微觀歷史之間的聯繫。

克羅埃西亞的行動分子Sasa Simpraga倡議重建過去提供大眾飲水的公共噴泉,讓公眾找到自己與所居城市微觀歷史的聯繫。 圖/鄭德恩提供

克羅埃西亞的行動分子Sasa Simpraga倡議重建過去提供大眾飲水的公共噴泉,讓公眾找到自己與所居城市微觀歷史的聯繫。 圖/鄭德恩提供

我想著,與主流之外尚未定義的事物產生連結,並不僅是將文化拓展到一個更大的領域,同時也迫使我們評估既定的領域,並且激發新的思考模式。這樣的想法在我與藝術家Dina Karadzic與Vedran Gligo談過之後,更為確認。Karadzic與Gligo為「駭客實驗坊」(Hacklab)的負責人,成員包括程式設計師與駭客。他們邀請我主持一個工作坊,因此我提議,是否可以設計一種程式語言,讓電腦在系統之外「運作」,甚至讓電腦在「有效地運作」上不起「作用」。這個問題讓我們重新審視對計算機運作邏輯(或自以為是)的理解,讓我們試圖扭轉我們過去的行事慣例。

活動舉辦之後,我開始思考,將人工智慧當作文化領域裡未來的觀眾,甚至是合作的夥伴,是否太過不著邊際;而在此刻,誰又是離我們最近的觀眾與合作夥伴? 我們已經和他們連結上了嗎? 這便是我在賈丁斯提弗工廠創作時所依循的方向。

或許已故的Kaloper聽到了我的心聲,經由介紹,我認識了表演藝術家Nina Kurtela,她現在租的就是之前Kaloper的工作室。工作室位於一棟住宅大樓裡,Kurtela搬進這間工作室後,才對其歷史有些了解。事實上,札格瑞布的藝術家一直享有政府提供的工作室,只不過如何申請這些工作室的訊息並不太開放。在這個工作室,Kurtela有時會舉行自己的活動,我便受邀發表一個表演《在111分鐘裡分享11件事物》(Sharing 11 Things in 111 minutes)。

我在這場演出中回應了自己在札格瑞布的經驗。那時我的想法是:一、要在三個月內接觸大批觀眾是不可能的,因為事先已經有人提醒我,當地藝術界對國外藝術家的興趣不大,就算是國際知名的藝術家也是一樣; 二、就像創立詩歌節的Simpraga所認為的,最重要的是留下一點痕跡,讓其他人有跡可循,即便這痕跡再小,也有其意義存在。

這場私人表演在一個半住宅與半工作室的空間演出,優點在於參與者都可感到的親密感以及和觀眾共享的時間。因此,我在表演中選擇了11種不同的事物(包括食物、酒、音樂、舞蹈、氣味等)來刺激觀眾,並且開啟不同的對話,以進入觀眾的個人記憶與他們每個人不同的詮釋中。最後,我特意留下一段長時間的停頓,讓每個人決定要向一個身處另一個房間的觀眾「演出」什麼。令我訝異的,眾人最後決定演出「一起小睡片刻」。在整個演出中,我首先選一條路線,但終結時,我們共同發展出一個新的方向。這個過程對我而言是很好的練習,不僅可以將自己與觀眾連結起來,還可以學著如何卸下自己的武裝,與他人建立關係,並創造一個大家都能保有主控權的情境。

雖然我只是一個過客,但我逐漸對札格瑞布產生歸屬感,尤其是Soldo為了回應我關於建築的概念如何和文化場館產生關係的問題,帶我訪問了應用藝術與設計學校(School of Applied Arts and Design)之後。原本我們計畫訪問的對象是建築圈的學生,沒想到這所學校不僅訓練學生成為未來建築師,更讓不同學生從15歲就開始學習織品、時裝、舞台設計,以及陶藝、繪畫和其他各種具有創意的事物。

我一方面羨慕這些學生身處這個保有開放態度的環境中,如此年輕便可以學習實用的技能,同時還能以抽象的方式思考;但另一方面,我不得不問,既然多年來,聰明的學生每年都畢業於如此先進的教育體制,學校以外可有孕育一個有活力的文化環境讓學生參與?這些學生未來是想投入目前的文化界,還是會須自己創造一個新的環境?

賈丁斯提弗工廠(Jedinstvo Factory)內部的空間。圖/鄭德恩提供

賈丁斯提弗工廠(Jedinstvo Factory)內部的空間。圖/鄭德恩提供

某天晚上,大概是我在賈丁斯提弗工廠的創作計畫開始的幾天前,我和剛認識的一個爵士鍵盤手一起去參加酒吧裡的即興之夜。那晚,除了一群準備上場的專業樂手外,還有一個由三個年輕男孩組成的團體。我的朋友不太確定他們是否是搖滾青年,也不確定他們是否知道如何即興地和其他人尬音樂。可是,他們一開始表演,觀眾就紛紛安靜下來,有人拿著起手機拍攝,觀眾裡頭還有他們的父母。我後來發現他們只有15到19歲,其中一個男孩告訴我,他們在自己就讀的音樂學院每年只能上台一次,因此,只能到處尋找更多演出機會。聽完我馬上想到,我應該跟他們分享賈丁斯提弗工廠這個平台,因為比起我,他們才是未來這個文化空間的觀眾與使用者。

我在賈丁斯提弗工廠的創作計畫,是不論未來這場館的建築會是什麼面貌,但現在就去實行未來的活動。在這個空間長達一周的駐留期間,我提出來的計畫包含錄像裝置、表演、音樂節目、排練、論壇、對話,還有吃喝玩樂,徹底把我駐村的計畫轉化為一個未來的藝術中心。

我一直沒有忘記,我的駐村其實是屬於一個更大體制內的計畫。除了我最後做的書面報告,這個體制可能根本認不出我是誰,也不知道我的作品提供了什麼樣的經驗、我的駐村的具體經驗,以及我在札格瑞布的文化圈裡所面對的挑戰。另一方面,也恰恰是這個上了軌道的體制,讓POGON得以促成我的駐村。不過,我無法滿足於僅僅是白紙黑字的報告,也拒絕接受這個體制裡沒有有血有肉的人。

於是我向Soldo詢問了在這體制裡,有份促成我的駐村項目的所有名字,然後寫信給每一個人,邀請他們參與我的計畫。結果如我所預期的,其中大多數人都無法前來,但幾乎每一個人都回信給我,提供他們對這個體制的看法,有些人更長篇分享。的確,我是受惠於體制資源的藝術家,但我更相信,大家都在朝著文化共同努力邁進,而非臣服於一個死水般的制度。除了效率之外,一個好的體制也應具備同理心和想像力,以維護一個由真實人民所推動的靈活文化之整體精神。

我最後在賈丁斯提弗工廠的活動開幕當天,氣溫是零下20度。儘管很冷,文化部還是來了一個人。 上次在爵士即興之夜表演的三個男孩和他們的父母一起來了,他們的表演吸引了一群小眾,有個女孩問起這個樂團叫什麼,才發現他們根本還沒替自己的團體取名字。

我還記得來參加開幕的第一位觀眾,她是札格瑞布文化資產局(Zagreb Conservation Department)的資深主管。 她說的一些話引人深思,「有時侯,我們在保存文藝復興時期的建築時,大眾與政府總是希望我們越快越好,但他們並不知道,建築的修復可能需要數十年的時間才算完成。我們每年都要做一份新的報告,來為我們的年度預算護航,爭取新的經費。在這期間,我們有時會經歷人事上的變動,有時甚至是一個國家的分裂!」

她在同一間辦公室待了很多年,她告訴我,「只有在國家分裂的時候,我才開始了解第二次世界大戰是怎麼回事。」我想她的意思是,只有保持謙卑的姿態,才能理解或順應不同的時期,人不應囿於眼前的局面,而是該將目光放遠,才能堅持不懈。

時間是個有趣的東西,我們必須與它合作,才能替現在和未來建立一些扎實的基礎,而這個基礎將是我們能夠得到與施予的禮物。我問那三個年輕音樂家的父母,明知沒有多少人能在音樂的領域出人頭地,為何還要支持自己的孩子追求夢想?他們的回答都差不多,因為這是他們孩子唯一感到熱情,下定決心去做的事情。其中一個爸爸說,他正考慮存錢送小孩到格拉茨(Graz)去深造。

當然,世界很大,我們都應該拓展視野。但是,一個藝術中心如果沒有具備才華的人在裡頭盡情發揮,扮演合適角色,那麼只關心它的未來建築會是什麼模樣又有什麼意義?於是我告訴Soldo,請她給那些勇於參與的年輕音樂家一個機會,讓他們現在就來計劃當前的節目。