海灘、沙漠、叢林、山脈、巨型都市、噪音污染、無端暴行、種族主義,再加上警察濫權與性愛旅遊,這就是拉丁美洲,不是隨便什麼人都可以來的。然而,世界各地的藝術家們,似乎對它越來越感興趣。文化上長期缺乏國家資源的挹注,卻又因為社會分配不均與洗錢的推波助瀾,而有了強大的藝術產出與火熱的藝術市場,要在拉丁美洲動盪不定的創作環境中生存,若不選擇仰賴門路取得當地的金援或房地產(常見的情況是與毒梟、礦業大亨有連帶關係的家族背景),就得與來自富裕國家的創作者建立夥伴關係。其餘那些由藝術家自己在當地慘澹經營,提供同儕交流平台的進駐空間,往往淪為所謂的「老美集散中心」(gringo hubs),不是變成撮合異國鴛鴦的桃花源,就是僅僅累積外國藝術家的資歷,並未真正讓當地激起化學反應。

拉丁美洲由33個國家組成,使用的都是殖民者的語言,也就是羅曼語族(Romance)。從墨西哥北部邊境開始,穿過中美洲與加勒比海,一直到智利最南端為止,講的是西班牙語、葡萄牙語和法語。拉丁美洲的面積約佔地球陸地的13%,人口至少六億,其中四億在17個國家裡講西班牙語,二億在巴西講葡萄牙語,另外的四千萬人則講法語、英語、荷蘭語,還有諸如奇楚瓦語(Quechua)、克里奧爾語(Creole)、馬雅語(Mayan)、艾馬拉語(Aymara)、納瓦特爾語(Nahuatl)、圖皮語(Tupi)等眾多原住民的語言。以圖皮語為例,從巴西的殖民初期開始,圖皮語一直是當地歐洲人與美洲原住民之間的通用語,及至18世紀,拉丁美洲的成員為了脫離殖民地的行列,創建自己的帝國,在一場標榜「獨立」並高舉「文明進化」的旗幟、實則進行文化滅絕的漫長運動之下,圖皮語終被打壓到近乎消失的程度。

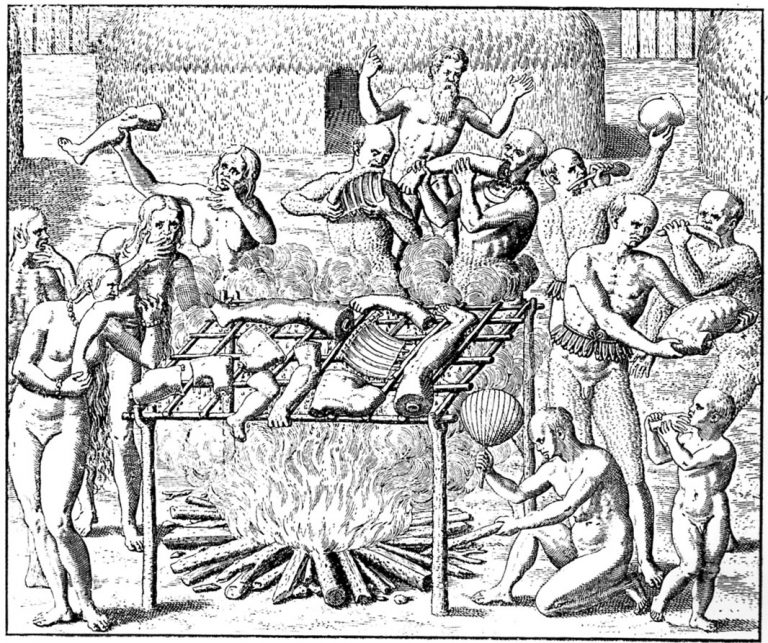

20世紀初,巴西現代主義(Brazilian Modernism)、墨西哥壁畫運動(Mexican Muralism)、烏拉圭建構主義(Uruguayan Constructivism)等前衛運動紛紛湧現,昭示了一個拉丁美洲的新時代;這些運動不僅回應全球社會與工業變革,也處理在地特有的議題:巴西詩人奧斯瓦爾德.德.安德拉德(Oswald de Andrade)於1928年發表的《食人宣言》(Anthropophagic Manifesto),正是其中一個標準的示範。該份宣言利用歐洲現代主義者對「食人」這項古老部落儀式的興趣,提出看法,將「食人主義」視為巴西展現自我的一條途徑,用來對抗歐洲在後殖民土地上的文化宰制。宣言中最經典的,是一句原本即以英文寫成的句子:「Tupi or not Tupi: that is the question」(圖皮,還是非圖皮,這是一個問題)。這話一面透過諧擬,暗喻「吃掉」莎士比亞;一面藉機頌揚圖皮人,因為據稱他們對敵人進行了同類相食的儀式;16世紀歐洲作家漢斯.史達頓(Hans Staden)便在其遊記《Collectiones peregrinatiorum in Indiam orientalem et Indiam occidentalem》中仔細描繪了這些「蠻夷行為」,內容與喬治.撒瑪納札(George Psalmanazar)所杜撰的偽民族誌《福爾摩沙變形記》(Historical and Geographical Description of Formosa)異曲同工。

二戰之後的權力移轉,讓美國置身於全球中心的地位;對拉丁美洲來說,殖民政權也由歐洲換成美國。1960年代到1980年代末,大多數拉丁美洲國家均為軍事或獨裁政權,政治流動與自由皆受到限制。當時幾乎所有拉美國家都陷入冷戰的氛圍裡,其中不少國家更在美國的支持下,透過「兀鷹行動」(Operation Condor)推翻民選的領導人,轉而建立軍事獨裁政權,延續所謂的「紅色恐慌」(Red Scare),亦即美國對共產主義政客與政黨莫名偏執的恐懼。

反獨裁示威運動,巴西聖保羅,1968。圖/卡蒂嘉.德寶拉提供

反獨裁示威運動,巴西聖保羅,1968。圖/卡蒂嘉.德寶拉提供

經歷過Bossa Nova誕生、拉丁美洲文學爆炸(Latin American Literary Boom)、美國向毒品宣戰,以及熱帶主義運動(Tropicalia)興起,許多拉丁美洲的藝術家不得不流亡海外。之後,隨著「民主制度的恢復」,曾在國際舞台上打滾過的藝術家陸續返國,開始經營一些文化交流的空間,他們以自己的住所、家產或閒置場所打造非正式的進駐計畫,來接待國外的藝術家。1990年代末至2000年代初,這些由藝術家所主持的計畫,相當程度回應了獨裁統治時期的拉丁美洲在藝術上缺乏體制支持的情況。

卡帕塞特(Capacete)即為這樣的一處所在。1998年,在法國研習歌劇,並以藝術家、舞台設計與攝影助理的身分遊走巴黎、維也納和米蘭的海穆特.巴蒂斯塔(Helmut Batista)回到巴西,創立了拉丁美洲最早的藝術家駐地空間之一。Capacete,葡萄牙語的意思是「頭盔」(譯注:其英文Helmet與海穆特的名字Helmut發音近似)。鑑於在地社區需要一個可以聚會、集思、投注時間的場所,正好海穆特又透過特殊的個人管道取得空間,卡帕塞特因此應運而生;最初設在拉帕(Lapa,里約熱內盧一個傳統波希米亞社區)的一處家宅裡,後來又遷至聖特雷莎(Santa Teresa)山上。這是一個風景如畫的社區,周遭被里約熱內盧市中心包圍,以蜿蜒狹窄的街道、為數頗多的藝術家人口聞名,是里約熱內盧最適合觀景的地點之一。

從聖特雷莎看過去的瓜納巴拉灣。圖/卡蒂嘉.德寶拉攝影

從聖特雷莎看過去的瓜納巴拉灣。圖/卡蒂嘉.德寶拉攝影

大約五年前,卡帕塞特的總部搬到海穆特自己設計、建造的新居,地點十分便利,就位於榮耀區(Gloria)一帶;這個一直「整建中」的空間,另外配備了不少支援的設施,包括一棟緊鄰在側、可以眺望瓜納巴拉灣(Guanabara Bay)的公寓;一塊靠近里約的山上野營用地,其間綴有幾處瀑布;一層置身傳奇的現代主義建築――科潘大廈(Copan)的套房,作為我們進駐聖保羅的據點。位於榮耀區的卡帕塞特是一座現代主義式棚舍,既像殖民地堡,又類似砲火肆虐下的巴格達公共生活空間,人們在此,時而發現自己與安德烈.弗雷澤(Andrea Fraser)一起做飯,時而與西爾維亞.費德里奇(Silvia Federici)一起用餐,或與亞瑟.林賽(Arthur Lindsay)一起喝啤酒。在意外邂逅國際大咖、看盡眼前里約的田園風光,並享受過這座城市各種放浪形骸的機會之後,原本欠缺舒適、隱私和安全感的種種不便,全都煙消雲散。但請注意!舉凡提款機詐騙、持槍搶劫或目擊兇殺這一類的事情,沒人可以免疫。遇到了算你倒楣!

作為藝術進駐空間,卡帕塞特並不生產作品,而是一個聚焦於當代議題的研究型智庫,關注人類、人類存在的方式、人類彼此之間的交流,以及人類與世界的相互作用。卡帕塞特善於聯繫不同領域的人才,協助他們進行研究。這也是一個認識朋友、適合一再重遊的好地方,許多在此駐地的藝術家均開發了長期的計畫,必須不斷回來,其中有些甚至搬到巴西,與當地人結婚生子。這些定義模糊的實驗計畫,一般而言通常在里約熱內盧與聖保羅進行,但也曾以展覽的形式遠赴法蘭克福的門廊博物館(Portikus),更曾以教育性活動的方式於上屆文件展的雅典展區露出。

1990年代,拉丁美洲出現許多藝術家自營的進駐空間,有些堅持至今,成為赫赫有名的先驅者,在這份名單上,除了卡帕塞特之外,還有1993年成立於阿根廷科爾多瓦的Casa13;它們從當初的非正式交流一路摸索,逐漸找到將自己的實踐體制化的途徑。然而,一直要到2000年,隨著越來越多具有左翼社會意識的政府掌權,這類空間才如雨後春筍般崛起,開始在拉丁美洲蔚為一股潮流。

其中,哥倫比亞是一個有趣的例子。在麥德林集團(Cartel de Medellín,1970和80年代活躍於國際上的專業販毒組織)被「銷聲匿跡」了十年後,哥倫比亞革命武裝力量(FARC)與政府之間的衝突因而「較為平靜」,像麥德林這類過去幾十年來暴力猖獗的城市,也因此從2000年開始,獲得了文化、都會發展與教育資金的挹注,致力發展出平和的居住環境,為拉丁美洲開啟了一段更加穩定、更少暴力,也更社會化的時期。

哥倫比亞革命武裝力量(FARC)與一位身分不明的小女孩在鏡頭面前持槍擺拍,攝於南哥倫比亞。圖 © 哥倫比亞國家警察、路透社

哥倫比亞革命武裝力量(FARC)與一位身分不明的小女孩在鏡頭面前持槍擺拍,攝於南哥倫比亞。圖 © 哥倫比亞國家警察、路透社

在此時空背景下,Taller 7於2013年的麥德林誕生。由七名視覺藝術家組成的團體所創立,Taller 7的成員雖然運用不同的媒材,但卻關注相同的議題,也就是既定體制外藝術實踐空間的缺乏(這是因為政府多年來忽視文化,加上大大小小的各種衝突所產生的後果)。七名藝術家聚在一起,合租一棟附帶露台的大房子,在那裡共享空間,也與其他人一起合作。這幢房子位於邦波納(Bomboná)一帶,靠近聲名狼藉的騷莎舞酒吧Eslabón Prendido,以及la Plaza del Periodista(在那裡可以買到大麻或小包古柯鹼,而且還附吸管)。Taller 7從創設之初便是一個以創作和實驗為主、聚焦於繪畫及自費出版的場域,很快地又開放展演空間,容納不同領域、背景與資歷的藝術家前來展覽、進駐,讓所有參與的藝術家與策展人在此生活、創作。Taller 7主要的基底不是它的硬體設備,而是這七位藝術家的專業知識,他們全心全意地建立聯繫、協助產製,最重要的是,他們也確保了大家在進駐期間都能安全快樂。

15年來,Taller 7一直藉著各種途徑、形式和組織型態自行營運,試圖透過另類平台建立新的連結點、創造新的交流管道,並經由演講、工作坊與展覽,將集體創作社會化。Taller 7是一個推廣視覺藝術的彈性平台,媒合不同的單位,例如安蒂奧基亞博物館(Museo de Antioquia)的麥德林國際交流中心(MDE),在那裡,藝術家與策展人能夠彼此認識,分享經驗。 Taller 7於2018年正式關閉,但在同一棟房子裡,目前正進行著另一項類似的計畫,由不同的藝術家團隊依照不同的方針營運,並取了一個不同的名稱:Lengua Negra,意思是「黑色語言」。

Lugar a Dudas是哥倫比亞的另一個例子,由探索哥倫比亞暴力的作品而聞名國際的藝術家奧斯卡.穆尼奧斯(Oscar Muñoz)於2005年所創,原名的意思為「一個懷疑的所在」。這個獨立的非營利空間位於卡利市(Cali),透過展覽、工作坊和駐地計畫,作為研究、討論、反思與批判性分析的實驗室,此外,這個空間還包括一個大型的檔案中心,收藏了以視覺藝術為主的近三千多本書籍、雜誌與錄像。

2006年,Lugar a Dudas於卡利市成立後不久,來自北美阿布奎基(Albuquerque)的湯尼.伊凡科(Tony Evanko)即憑藉傅爾布萊特研究獎助金(Fullbright Lecturing and Research Grant),從美國新墨西哥州遷至麥德林。他與聖地亞哥.韋萊茲(Santiago Vélez)一起在麥德林成立了一個非營利的藝術家自營中心C3P(Casa Tres Patios,意思是「三個庭院」)。 C3P最初作為另類空間、藝術實驗室與展覽場地,讓本地藝術家體驗、發展與展示種種實驗成果,接著,該處亦很快地成為一處駐地空間,與相鄰的 Taller 7各自接待前來造訪的藝術家。

同樣是2006年,瑞秋.施瓦茨(Rachel Schwartz)在玻利維亞的聖克魯斯市(Santa Cruz)打造了一個獨立的另類藝術空間Kiosko,亦由藝術家們自行管理。這是一個創作、推廣和培育當代藝術的平台,對象不分在地或全球。使用上包括辦公室、設計與建築工作室,以及藝術家進駐、展覽、舉辦活動的空間。除了策劃並主辦一個國際駐地計畫之外,Kiosko亦製作教育相關的活動,並將玻利維亞的新銳藝術家推廣至國際舞台上。

Lugar a Dudas的正門,圖中亦可見凱文.曼瑟拉(Kevin Mancera)的作品。攝於哥倫比亞卡利市,2012年。圖 © Lugar a Dudas

Lugar a Dudas的正門,圖中亦可見凱文.曼瑟拉(Kevin Mancera)的作品。攝於哥倫比亞卡利市,2012年。圖 © Lugar a Dudas

Kiosko位於玻利維亞聖克魯斯的展場。圖 © Kiosko

Kiosko位於玻利維亞聖克魯斯的展場。圖 © Kiosko

新聞工作者邁克爾.瑞德(Michael Reid)在其2008年出版之《Forgotten Continent: The Battle for Latin America’s Soul》一書中提到,拉丁美洲「既不像非洲那樣窮到足以喚起道德十字軍,也不像印度或中國那樣經歷爆炸式的繁榮,因此很大程度上被西方忽視了。然而,這個擁有五億人口、全球8.5%石油儲量,以及世界最大可耕地的廣袤大陸,正忙著在政治與經濟上改頭換面。」關於這點,他是對的,儘管2008年發生全球金融危機,拉丁美洲卻享受著「粉紅浪潮」(Pink Tide)或「向左轉」(turn to the left)的美好時光。經過幾十年的壓迫、剝削和不平等待遇,拉丁美洲的民主化開啟了新的可能,儘管新自由主義的全球洪流來勢洶洶,民意仍前所未有地轉向左翼政府,標誌出一個歷史性的變遷,試圖透過更為進步的社會經濟政策乘上粉紅浪潮的勢頭。

彼時巴西的經濟發展特別繁榮,更與俄羅斯、印度、中國並列金磚四國,因而引起國際間的興趣,各路資金紛紛湧入,連文化領域也不例外。由於殖民歷史的爭端,過去像西班牙這類國家一直未能涉足巴西,如今終於找到介入的理由。不過,西班牙受到那場金融危機的嚴重衝擊,可挹注的資源著實有限,只得以他們擁有的籌碼下注,亦即文化、政治價值與外交政策這些傳統、美好、非強制性的「軟實力」。

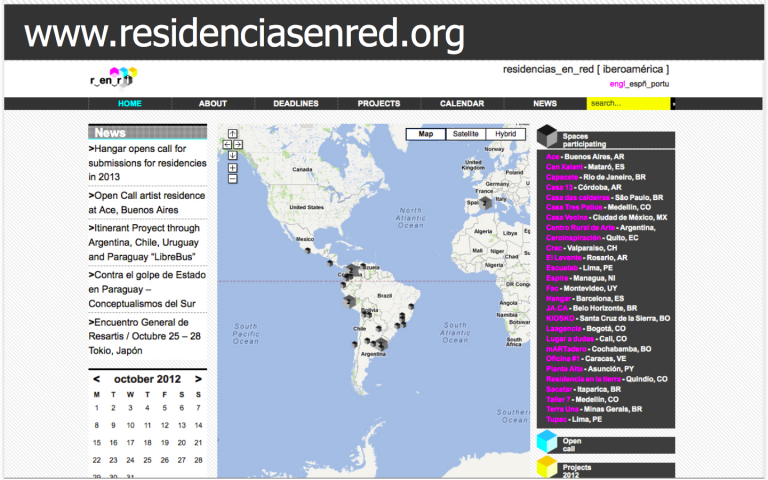

2008年,幾乎在拉丁美洲所有的西語國家裡都設有據點的西班牙國際合作發展署(AECID),首次於聖保羅成立了辦事處。由安娜.托美(Ana Tomé)領軍,AECID在聖保羅植下種子,其中之一名為 「伊比利美洲駐地網絡」(residesias_en_red [iberoamérica] ),這是一個伊比利美洲網絡平台,由27處空間組成,致力於當代藝術與文化的研究、產製和展覽,透過平台在14個拉丁美洲國家與西班牙之駐地計畫進行串聯。基於西班牙在拉丁美洲(尤其是巴西)戰略布局的需求,「伊比利美洲駐地網絡」和許多來自國外的文化投資一樣,被包裝在「區域整合願景」的名目之下;儘管背後帶有真正的政治動機,這個計畫仍在拉美藝術界帶來非常正面的影響。

2008年初,「伊比利美洲駐地網絡」只有八個成員空間,及至2010年已集資聚合了27個,而這只不過佔了藝術進駐空間的一小部分而已,拉丁美洲從來不缺那些更上軌道、更具政治色彩、更加熱門的進駐空間。在這塊土地上,過去曾有、現在也還不斷有新的類似機構,而「伊比利美洲駐地網絡」的首要任務,便是加強這些機構(無論是否為其成員)之間的交流;AECID所提供的資源,使藝術家、贊助者與其他空間都能透過「伊比利美洲駐地網絡」看到這些類似的藝術組織。以國際文化政策的微觀與宏觀層面來看,此舉都推進了拉美藝術駐地的整體展現。以哥倫比亞為例,當時網絡的成員舉辦了一次會議,召集其他性質類似的駐地空間(不一定是網絡成員),共同成立一個全國性的聯盟,要求政府在國立、省立與市立的層級上,分別發展特定的藝術駐地政策與獎助;而這些政策與獎助,至今依然運作不輟。

2012年,當AECID停止贊助「伊比利美洲駐地網絡」時,該網絡的成員與非成員均已具備卓越的能力,可以透過國際合作來籌資,並調整其計畫,以適應拉美環境中不斷捲土重來的經濟與政治動盪。其中,有的空間原本就隸屬於外面更大的國際網絡(像是由英國出資的Triangle Network),這些空間便開始針對複製了類似網絡模式的國際出資者加強聯繫。例如,2007年成立的藝術合作社(Arts Collaboratory),在彌補「伊比利美洲駐地網絡」的未竟之功上,即扮演了十分重要的角色。由荷蘭的DOEN和HIVOS基金會發起,藝術合作社於2013年重新設計了一個修正版的計畫,以促進永續的、合作的和開放的視覺藝術實踐,裨益社會創新,並在非洲、亞洲、拉丁美洲、中東等25個參與組織裡,建立跨地方的社群。

未來的前景並不振奮人心。過去十年裡,拉丁美洲的「粉紅浪潮」已為新自由主義的洪流所染。如今,警察與示威者在智利、厄瓜多爾、玻利維亞和海地的街頭發生衝突,有如2011年委內瑞拉與2013年巴西場景的重現。這一次無需軍事干預,只見民眾的抗爭。透過惡質的媒體操作,極右翼的黑暗時代在民主的認可之下再度回歸,其背後的靠山依然是代表跨國公司利益的美國。拉美的藝術駐地空間在右翼政府的暗影之下,必須轉型才能力求生存,而教育的崩潰則發出警訊,敦促我們再度填補社會動盪不安所造成的缺口,重新思考其他更為平等的教學方式,而這些或許可以從藝術上的經驗開始。

於波哥大的查皮內羅(Chapinero)社區發起的Laagencia,是一個始於2010年的集體藝術創作計畫,發展的歷史尚稱年輕,正好示範了藝術家自營空間如何調適與再造。同樣為「伊比利美洲駐地網絡」 的前成員,Laagencia最初是一個用來進行藝術計畫的辦公室,早年提供展覽與駐地空間,現已轉型成一個開放式的教育計畫,稱為「車庫學校」(Escuela de Garage),讓參與成員得以在過程中清楚地表達各種迫切、突發或偶然的問題。它在現階段激發了藝術實踐的辯證;這些實踐試驗了不同的工作策略和方法,以提出調解的方式、公眾活動的協作、自主發表出版,以及與他人一起產製、傳播知識的另類途徑。車庫學校由五位藝術家組成,不分階級,大家都是主導者、製作者和參與者。

計畫參與者於卡帕塞特共度週三,攝於2015年的巴西聖保羅。圖/佩卓.維多.布蘭道(Pedro Victor Brandão) 攝影

計畫參與者於卡帕塞特共度週三,攝於2015年的巴西聖保羅。圖/佩卓.維多.布蘭道(Pedro Victor Brandão) 攝影

無獨有偶,2015年,卡帕塞特也重新設計駐地模式,調整為一個調度靈活的學校計畫,供參與者、講師和顧問之間彼此交流。該計畫目前為期九個月,由九名來自不同背景的講師主持為期三到五天的研討會,並舉辦開放給當地民眾的講座。此外,全年還與其他客座講師或進駐的參與者共同籌備各式各樣的活動,包括演講、表演、出版、展覽、論壇等。

同樣地,Lugar a Dudas也創立了專屬的教育計畫「無形學堂」(Escuela Incierta),這個教育計畫並沒有實體學校,而是從獨立藝術空間出發,重新審視教學動能,以及不同社群在特有環境中所形成的自我組織與自我學習模式,試圖從藝術實踐的角度重新思考無層級或非正統教育,並透過這些經驗,再次引發我們反思教育的社會功能,以及計畫的促成者和社會行動者在過程中所扮演的角色。

新自由主義對環境造成的威脅也推動了跨域計畫,結合藝術與其他領域,例如環境永續、科技發展等議題,以合作學習的可能性,面對未來的巨變。

2006年,「伊比利美洲駐地網絡」的另一個前成員Centro Rural de Arte在阿根廷成立,以跨域平台讓不同知識背景的人相互交流,透過駐村、工作坊、講座等方式進行創作和研究,其中有些活動是游牧式的,交由固定合作的空間暫時主持。Centro Rural de Arte將能量導向出產原材料的地方,並對社會形態、自然多元性之間的交互關係進行試驗;自2013年以來,他們已在距離薩拉迪洛(Saladillo,位於布宜諾斯艾利斯省)12公里處的卡松村(Cazón)展開一些活動。此外,在巴西也有類似的藝術組織,例如Terra Una、Silo和Nuvem,位於哥倫比亞麥德林的Platohedro亦致力於結合藝術、環境、科技與教育。