5月初,我因為足跡經過萬華一帶,收到來自疫情指揮中心的細胞簡訊。在疫調尚未明朗的時刻,這封訊息讓辦公室人人自危,同事們紛紛向我確認近期足跡,隱晦地探問為何下班不直接回家,到處跑要做什麼。我陷入自責和被誤解的不滿,天天上演內心的小劇場。

「妳被當成病毒了。」印尼移工朋友Toni聽完我的遭遇,犀利點評。沒等我回話,他隨即笑笑地抱怨,就像他總覺得來臺灣工作以後,好像一直在健檢抽血,疫情爆發至今,還得不時被臺灣同事叮嚀假日別亂跑。再這樣下去,可能整個廠的移工都要被叫去快篩戳鼻孔。

「因為怕我們有病啊。」他說。

我想起前陣子苗栗移工宿舍的群聚感染,徐縣長被問到移工禁足的爭議時,振振有詞地說著「確診了哪來人權」,然而病毒不分國籍,只對移工進行管制,本就是對特定群體的歧視。被禁足的移工,被當成病毒的移工,會不會像我一樣感到不平或恐懼?他們在疫情期間經歷了哪些遭遇?

去年的「移民工文學獎」,已經有不少入圍及得獎的作品寫下疫情期間的經歷,有人無法回印尼幫兒子慶生,有人擔心自己在異鄉染疫不治。當時評審提到,從檔案保存的角度看這些以疫情為主題的移工書寫,可以讓未來人們回顧武漢肺炎時,了解不同社會位置的人各自受到什麼影響。

這也是為什麼疫情下的移工創作顯得格外重要,無論是站在弱勢發聲的立場,還是做為歷史見證的檔案留存,我們都必須更細緻地爬梳官方宏觀的防疫敘事背後,尚未被主流社會聽見的聲音。我們成立的「Trans/Voices Project」(簡稱TVP)團隊 1 便是以這樣的想法為起點,試圖用不同藝術形式的活動,與移工一起進行疫情下的創作及對話。

透過工作坊以詩歌創作為主題,希望讓移工朋友有機會沉澱並寫下自己在疫情這年的感受。起初TVP團隊計畫邀請印尼作家Selvi Agnesia來臺灣,與喜愛寫作的移工們交流,但受疫情影響,許多跨國的藝文交流停擺,最後我們改成自己帶工作坊的形式,和屏東祈禱室的印尼朋友一起創作詩歌。

屏東祈禱室是由屏東的印尼移工及新住民共同籌辦的宗教空間,每到週末,許多移工和留學生就會聚在祈禱室禮拜、煮飯共食。TVP團隊成員吳庭寬在祈禱室教中文,所以我們選在祈禱室的中文課後舉辦詩歌工作坊,並搭配該週中文課的內容,教大家許多與情緒感受有關的中文形容詞,做為後續集體創作的暖場。

希望這場詩歌工作坊可以鼓勵大家以COVID-19為題寫一首詩,但想到如果過去很少寫作經驗的朋友,聽到即席創作可能會有壓力,為了引導大家拋出自己的想法,帶動集體創作的能量,我們以問答的方式設計這場活動。

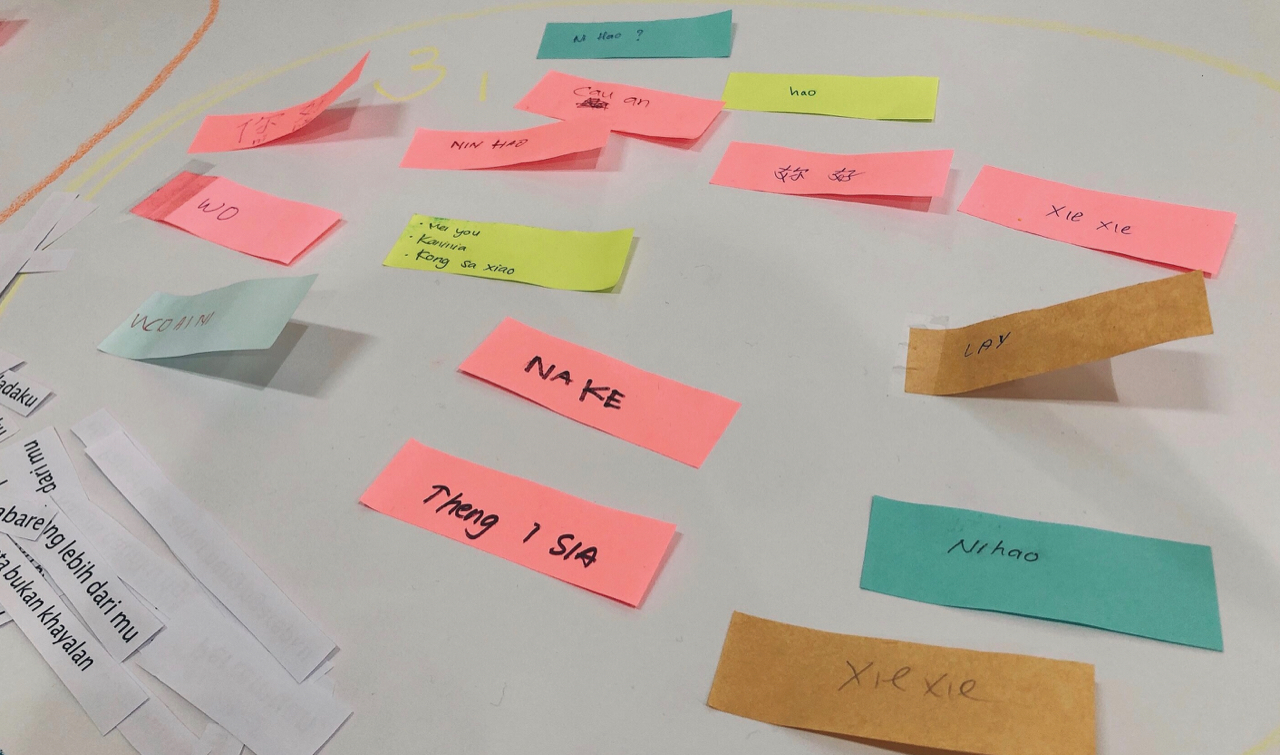

首先我們擬了幾個問題,請大家把答案寫在便利貼上面貼出來,這些問題包含:你第一個學的中文單字是什麼?請形容家鄉的味道?同時我們也列印一些印尼歌曲的歌詞,剪成一條一條的單字和句子,這些歌都是印尼家喻戶曉的大眾歌曲,不少人看到一行歌詞就能哼唱整首歌。

這些問題讓大家回溯自身移動的生命經驗,有人第一句學的中文是「等一下」,有人最先學會說「累」,因為工廠是忙碌的流水線。有人說家鄉的味道是稻穗成熟的香氣,也有人說是爸爸身上的汗味。

問完所有題目後,我們邀請大家從這些便利貼和歌詞挑出五張做為素材,以COVID-19為題寫詩。

詩是斷裂的語言,可以容許詞彙的拼貼、天馬行空的字詞排列。這些便利貼上的答案和歌詞,除了是文學創作的詞庫,更重要的是把平時不會表露的感受,例如愛、想念、氣味,透過他人寫下的答案,偷渡自己的真實情感在詩作當中。

儘管是指定題目的創作,但大家很快地完成作品,甚至拿起蠟筆在自己的稿紙畫上五顏六色的邊框。或許是因為詩歌是保留虛構空間的文體,融入耳熟能詳的歌詞和他人寫下詞語後,反而給創作者更大的空間,自在地表達內心想法。

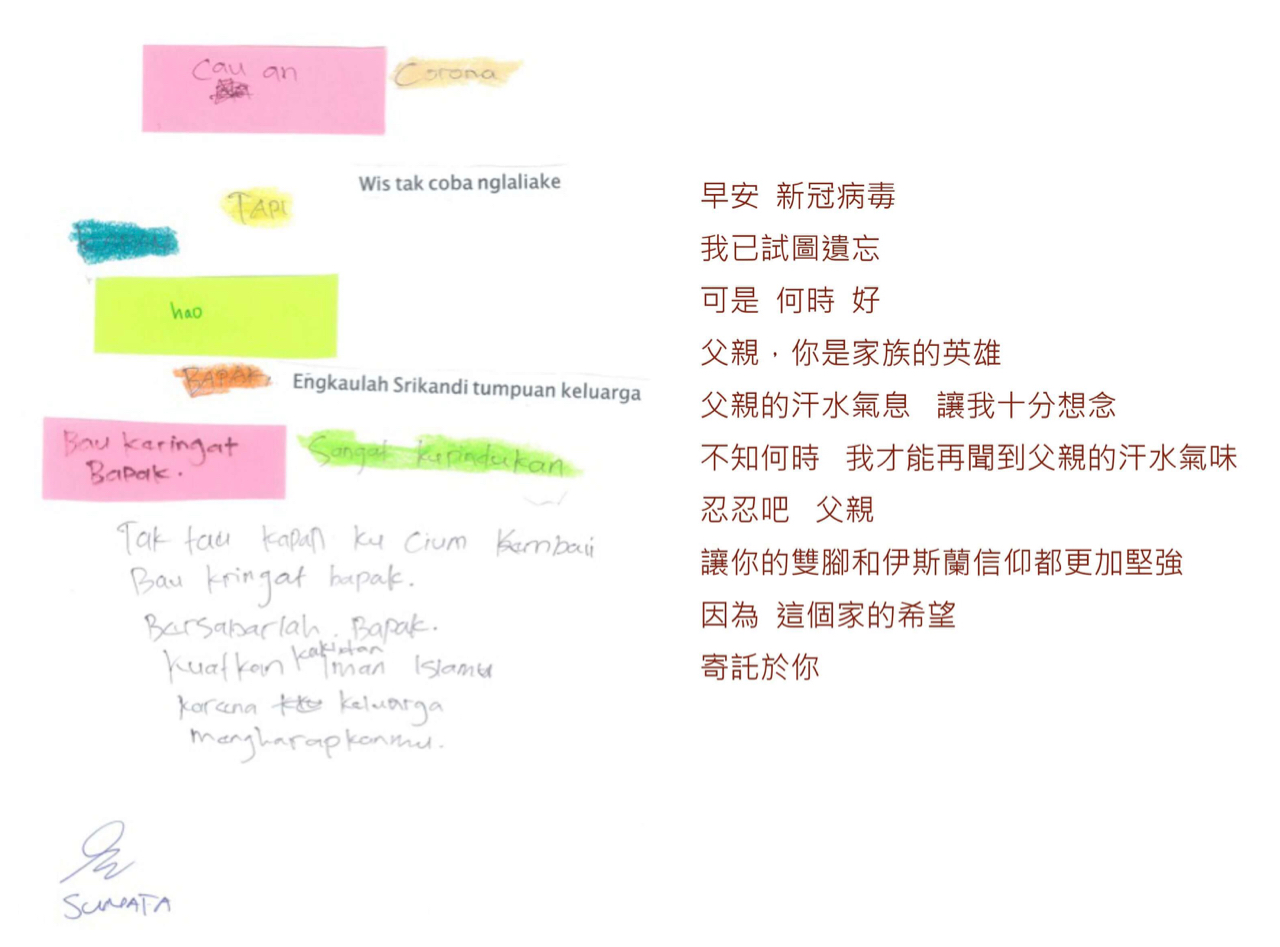

最後朗讀詩作的氣氛很熱絡,有人寫出逗趣的內容引起眾人大笑,也有人讀完詩作後集體靜默,陷入惆悵感傷的氛圍。所有作品中,印尼移工Nata寫的詩情感格外強烈,他以自身經歷,描述他對家鄉父親的掛念。

屏東祈禱室的詩歌工作坊,來自印尼的Nata寫出心繫父親病情的作品。圖/Trans/Voices Project提供

屏東祈禱室的詩歌工作坊,來自印尼的Nata寫出心繫父親病情的作品。圖/Trans/Voices Project提供

今年是Nata來臺灣工作第三年,本該是盡情體驗異鄉生活的年紀,卻接到父親突然中風的消息。因為疫情,他不便丟下工作回印尼,只能每天都握著手機與印尼家人視訊,時刻關心爸爸的病情。年幼時母親病逝的經歷,讓Nata害怕又會失去父親,在他寫下這首詩的同時,正面臨著是否該續約留在臺灣工作的抉擇。

工作坊結束後三個月,Nata結束合約,回印尼照顧臥床的父親。近期他在家鄉買了一台餐車,自己開業賣牛肉丸湯。或許就是因為這場疫情,拉開空間的距離,讓他更明白自己對親人的重視。

另一位近期回印尼的移工朋友,是屏東祈禱室的創辦人Idi大哥。在臺灣工作超過十年的他,此次回印尼是為了陪伴病重的母親,目前沒有再來臺灣的規劃。Idi對文學的熱愛讓我印象深刻,過去他不僅是印尼母語雜誌的專欄作家,甚至曾即席創作Pantun(班頓,馬來傳統詩體)朗誦給我聽,我非常珍惜他與我分享的書寫作品及生命故事。

Idi回國前幾天問我是否再見一面,但身處疫情熱區,只能透過電話向他道別。最終他悄悄地離開臺灣,活躍於在臺印尼移工社群的他,沒有在社交平台公佈自己已經回去印尼的消息。疫情限制了我們的行動,也阻隔與親朋好友送別的機會。

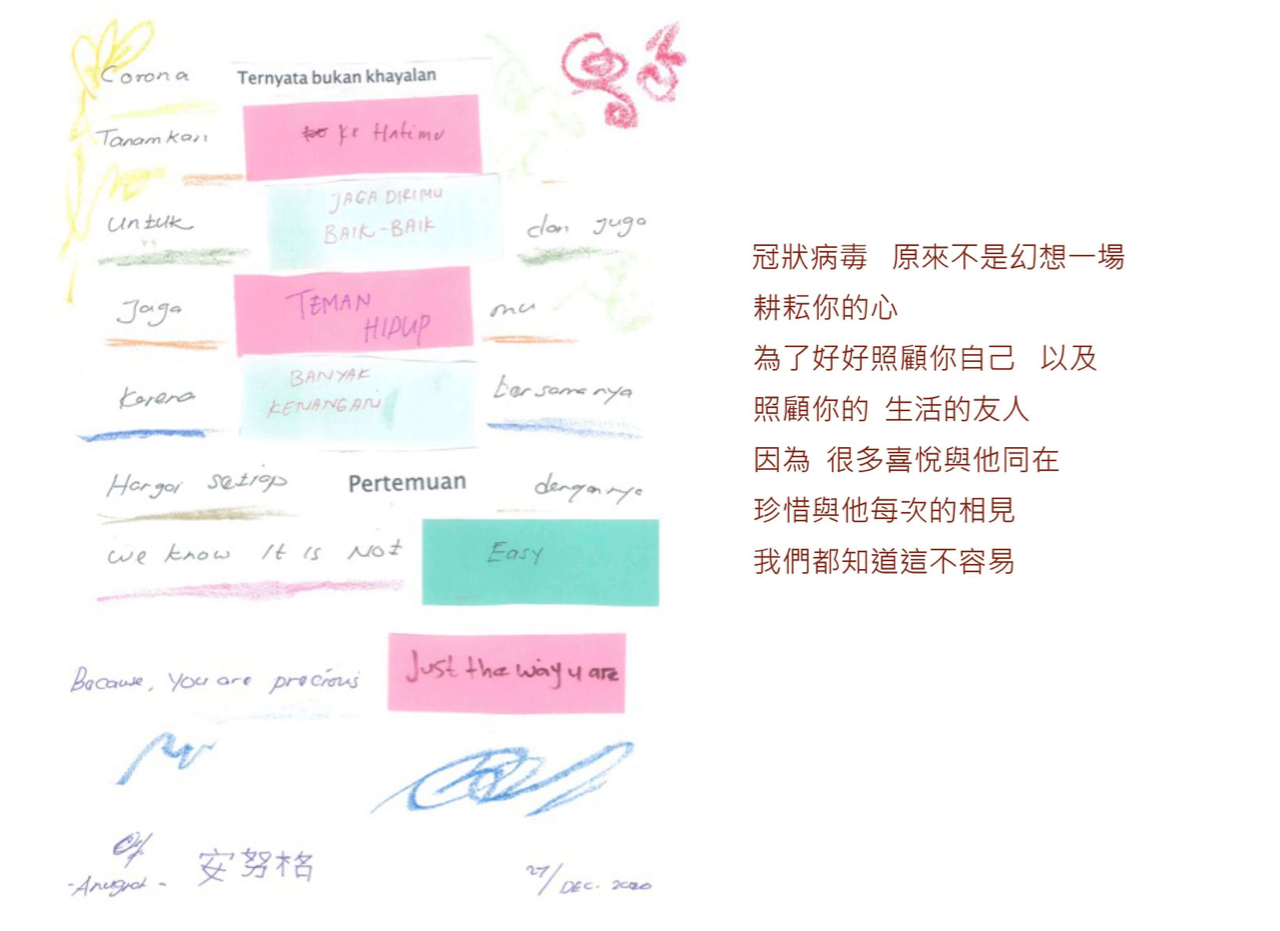

這幾天我回頭重讀工作坊的詩作,發現印尼留學生Anugrat的詩作雖然是運用許多便利貼和歌詞素材串成,卻寫出我近日無法與好友Idi當面道別的惆悵感受。

此刻讀Anugrat寫的詩,才切實感受到疫情下的我們都該珍惜每次相見,因為疫情時代的每一次再見,或許就是永遠的道別。

屏東祈禱室的詩歌工作坊,印尼留學生Anugrat的詩,以疫情下的相見與別離為主題。圖/Trans/Voices Project提供

屏東祈禱室的詩歌工作坊,印尼留學生Anugrat的詩,以疫情下的相見與別離為主題。圖/Trans/Voices Project提供

這場詩歌工作坊我們收集了17首詩作,由TVP團隊成員藍雨楨翻譯成中文,在4月的新住民市集展出大家的手稿,並邀請祈禱室的移工朋友Muri上台朗誦自己寫的詩作。為此,Muri很慎重地將自己的詩作擴寫,搭配其他祈禱室的夥伴現場彈奏配樂,朗誦三分多鐘,許多台下的印尼朋友聽到他的朗誦,紛紛流下眼淚。

原來許多參加市集的朋友,都是迫於疫情無法回鄉的移工和新住民,大家掛念著遠方的家人,卻總是默默消化這些擔憂。Muri寫的詩以思念故鄉的親人為題,配上情感豐沛的表達,讓許多人聽了深受感動,瞬間,原本氣氛歡樂的新住民市集,變得有些感傷。

在新住民市集朗誦詩作的印尼移工Muri。圖/Trans/Voices Project提供

在新住民市集朗誦詩作的印尼移工Muri。圖/Trans/Voices Project提供

面對疫情的三個提問,團隊收到最多的回答,是希望疫情後可以「回家」。圖/Trans/Voices Project提供

面對疫情的三個提問,團隊收到最多的回答,是希望疫情後可以「回家」。圖/Trans/Voices Project提供

當天市集的攤位,我們設計了關於疫情的問答小互動,提出三個問題,請大家把答案寫下來貼在板子上,分別是:疫情讓你想到什麼?疫情讓你失去什麼?疫情結束後你想做什麼?

許多經過攤位新住民姐姐熱情響應,認真寫下自己的心聲,其中讓我印象最深刻的一題是疫情後想做什麼。要是現在問臺灣人,一定很多人說疫情結束想出國、想出去玩。但我們收到最多的回答,是希望疫情後可以「回家」。

如果說與移工一同探索創作的過程是相互學習的鏡子,當天新住民市集短暫出現低迷的思鄉氣氛,以及一張張寫著想回家的字條,都讓我意識到原來在武漢肺炎爆發這一年多來,台灣還有一群移民和移工朋友,長期活在擔憂故鄉疫情、無法回家的無奈。

移工在疫情下的詩歌創作,既是釋放他們內心的情感,也是疫情時代必須被正視的聲音,在武漢肺炎的影響下,其他國家也出現許多與疫情相關的書寫。今年4月,新加坡的孟加拉移工詩人出版散文集《Stranger to My World》,記錄下他在移工宿舍隔離那段時間的生活日記;去年臺灣出版郭晶的《武漢封城日記》,更讓大家開始發現,市井小民的生活紀錄,似乎是官方發佈消息之外更貼近真實的觀點。

這次的移工詩歌工作坊是一個新的嘗試,也是與移工共同創作及對話的契機,只要疫情未歇、不平等仍在,我們依然會支持並關注移工,如何運用不同的發聲媒介,對臺灣社會提出叩問。