北京正在經歷一個詭異的時刻,或者更確切地說,北京正處於永久無常歷史的正常時刻。自1980年代以來,這座城市一直保持著中國地下/另類文化之都和權力中心的矛盾地位。由於北京有藝術和電影學院、租金低廉,而且北京也相當國際化,且沒有上海因殖民歷史而蘊含的負面影響,因此是中國無可爭議的地下音樂中心,也可以說是中國當代藝術從邊緣被推向國際舞台的源頭。

但事情發生了變化,2017年的夏天,胡同裡突然出現了大量的商店,以及同年11月移民工人和小工廠被迫搬遷事件,都突顯了這種改變。雖然這些變化似乎很突然,但它們代表了長期進程,是北京都市更新為更加官僚化集中管理的首都計畫的一部分。這個城市的轉型不太可能直接針對一小群擁有特權的音樂和藝術製作人,而且因為提供了改善住宅環境的機會,可以說是具有利他主義的面向,雖然這是依照政府的願景而進行的計畫。

然而,有意或無意地,次文化活動被擠出首都。如果有樂觀的一面,那就是創意活動被重新導向全國各地,但這個結果依據一般國外地下文化的標準來評估,是否能夠持續,並且具備足夠的識別度,仍有待觀察。如果文化分類中的「地下」文化定義為不以追求利潤為主要目的的非主流活動,而且不管是刻意或無意地都不受到媒體的關注,並且透過自己的網路進行傳播,那麼這個詞就很難適用於當代超網路系統的中國,在這裡一切訊息都可透過網路取得。但由於缺乏更好的選擇,這個詞本身仍然可以用來形容某種逆向的創造性衝動(contrarian creative impulses)。

反思北京的聲譽,我們可以想到在D22(2006至2012年營運的著名音樂場地)的鼎盛時期關於這個城市音樂場景的故事,今天仍然獲得許多迴響――北京骯髒且工業化,因此這個城市的音樂家也聽起來具備骯髒且工業化的風格,繼承了紐約的無浪潮(No Wave)和柏林的後龐克。實際上,我們不難想像北京與柏林的相似之處。北京的汙染、煙囪和寒冷的冬天讓人很容易聯想到東歐給人的刻板印象,並且這兩個城市共同擁有(雖然規模小而逐漸消失的)類似的建築遺產(如構成798藝術區核心的包浩斯工廠)。在迎接2008奧運和之後的幾年裡,對於年輕的中國人和外國人來說,北京如同承諾創造了一個新柏林的化身,人們可以在政治壓迫的夾縫裡,弔詭地尋找自由的空間,過著混亂且廉價的創意生活。街道上有警察,也有空的建築物,地下排練空間的樂隊盡可能地發出許多噪音,還有煙霧繚繞的酒吧⋯⋯

曾經,北京猶如新柏林的化身,同樣骯髒且工業化,並擁有類似的建築遺產(如圖之798藝術區),人們在其中開鑿混亂且廉價的創意生活。圖/Wikimedia Commons

曾經,北京猶如新柏林的化身,同樣骯髒且工業化,並擁有類似的建築遺產(如圖之798藝術區),人們在其中開鑿混亂且廉價的創意生活。圖/Wikimedia Commons

當然,傳說總是聽起來很棒。但這只是一個傳說而已――當時(或實際上在1990年代),各種音樂場所被拆除和關閉仍然經常發生。這些地方留下來的音樂遺跡現在在哪兒呢?當時備受讚譽的樂團大多演奏一種音調優美的吉他流行音樂,只有少數人參照了衝撞當代的前輩,並且更少的人(應歸功於White和蘇維特波普(Soviet Pop))重新挪用其聲音的影響力創造奇特和風格新穎的音樂。今天,北京的音樂以堅毅、原真和噪音聞名,但回顧北京音樂的發展,大部分時間都與現實不符。

另一方面,音樂像中國的許多其他事物一樣,已經貨幣化和加速發展,這樣的專業化對於組織和產業結構來說,絕對是值得歡迎的變化。但通過不斷擴展的摩登天空(Modern Sky)或太合音樂集團旗下的赤瞳音樂(Ruby Eyes)這樣的唱片公司,獨立搖滾音樂早已成為一個產業。《中國有嘻哈》就是值得一提的例子,雖然這個比賽節目崛起於另一個不同的社群,卻將中國的嘻哈文化從地下非主流推到了萬眾矚目的媒體中心,甚至引發國家審查的強烈反對,而這些事情都在短短一年內發生。事情發展得太過快速,導致許多樂團圍坐在酒吧裡的奇特景象,他們聚集在一起是想趕快被選中簽約,就能辭掉現在的工作。這個景象在紐約或是倫敦幾乎都不可能發生,因為西方音樂產業正不斷萎縮。除了這個令人費解的現象,圍繞音樂的系統已經發展穩固,但內容仍處於一個曖昧不清的狀態,有許多的音樂節與樂團巡迴發生,但市場上每年真正值得建議聽眾聆聽的好專輯仍然很少。

公平來說,北京仍然存在不那麼循規蹈矩的音樂,但很難說它代表了某種時代精神,這種音樂也很難既保有激進的潛力,又吸引廣泛大眾的喜愛。由薩克斯風樂手王子衡、昔日的噪音吉他手李劍鴻和筆電即興音樂創作者Vavabond等人領軍而重獲活力的噪音方興未艾。2018年,王子衡和朋友們開始在靠近長城的荒野舉辦小型戶外音樂節,讓噪音和即興創作的脈絡重新遠離城市,並藉由邀請日本噪音團體Astro(最初是C.C.C.C.的長谷川洋創立的計畫),加強與日本噪音場景的聯繫。

在長城腳下舉辦的戶外音樂節「荒音祭」,王子衡、大傅與WV Sorcerer Production巫唱片主辦。圖/張晶蕾&GEEK SHOOT JACK films攝影,荒音祭提供

在長城腳下舉辦的戶外音樂節「荒音祭」,王子衡、大傅與WV Sorcerer Production巫唱片主辦。圖/張晶蕾&GEEK SHOOT JACK films攝影,荒音祭提供

然而,儘管北京擁有某些優勢,那些讓非商業、非主流音樂在北京茂盛發展的因素正在逐漸消失。五年前,人們可以很容易地形容北京對於玩音樂的人來說是生活費低廉、堅韌不拔、令人興奮的環境,最重要的是,這裡可以說是音樂網絡與系統的中心,但是現在很難這麼說了。

當代藝術也有類似的例子,出生於內蒙古、在北京發展的藝術家尉洪磊2015年在《Kaleidoscope》雜誌的採訪中,就大大抱怨北京的生活環境,他說:「我沒有搬到另一個城市的唯一原因是我必須和我的雕塑工廠密切合作。」尉洪磊的雕塑工廠關閉後,他搬到重慶,這裡突顯的問題是當其他創作者留在北京的理由消失後,他們會怎麼辦?

上海對於這些創作者是一大誘惑,因為新興畫廊和國際合作增加,上海的藝術場景可以說已經趕上北京。拜ALL Club(由防空洞酒吧的前團隊經營)成立之賜,這座城市已經成為國際前衛電子音樂地圖的重點之一,不僅是國際巨星的巡迴演出之站,也是Tzusing、Hyph11e、Scintii、Osheyack等製作人以及Genome 6.66 Mbp等唱片廠牌藝人聚集之處。他們的音樂受到外國媒體重視,也為歐洲知名樂手和DJ所知。上海讓全球媒體界開始關注另類音樂和青年文化,而這是北京很長一段時間沒有達到,或者說從來沒有過的影響力。值得注意的是,在上海活躍的音樂人有些來自臺灣、亞洲各國或美國,顯示上海具有強大的國際吸引力。

上海的崛起讓人興奮,但也招致批評,如果說上海的創意與網路社群的連結超過和在地環境的關聯,那這些影響力真的算是來自上海嗎?上海電子音樂在國際上引發的熱潮可能只是反映出觀眾從加速的城市發展中對中國未來景觀的投射,而不是完全由在地產生的美學。甚至Genome 6.66 Mbp的聯合創辦人Tavi Lee也於2018年稍早時在《Bandcamp Daily》平台發表了較悲觀的看法:「人們常過度誇大和迷戀中國,或許將其視為一種崛起的未來力量,將拯救西方明顯的停滯狀態。事實上,在中國除了『官方文化』之外,任何事物要在這裡生存都變得越來越難。中國的未來不會有好的政黨,只有人工智慧的大規模監控和強制執行。」

這並非完全不可能,但希望事實並非如此。然而,基於這些東方主義幻想投射問題和上海夜生活的薄弱地位,從長遠來看,可能更令人興奮期待的反而是中國知名與先進城市之外發生的事情。

2018年7月份,我和一位藝術家一起去了武漢,檢查裝置作品的部分進度。我們在一個被稱為「光谷」的地方會面,此處經常停電。我們搭了計程車,快速經過低樓層公寓和轉變為建築工地的空地,突然間來到了新建的大學校園裡。走了幾階樓梯,我們來到一間大閣樓,兩個20多歲的人正在聽迷幻搖滾,並且用電腦將LED燈的光線與音樂的節奏同步。

這是中國未來創新的面貌。有許多的廣告看板和政府口號鼓吹「創新」和「創業」,我們不應該全然相信,但有足夠的錢被拋到這個問題上,所以事情最後仍會有所改變。問題是這些新的創造活動是否能夠成就一些依照現有標準認為是高價值的成果。就像是利用音樂軟體創造演算法生成的聲音,或者是變化多端的視覺投影,不必然等於創作讓人難忘的歌曲,或是發現有趣的聲音,或者甚至使用這些科技的材料來創作超越「科技」概念本身的裝置作品。在創作發展的過程,形式會不斷演進,新媒體能夠讓新形式的內容流通,所以我們也該調整對新形式創作的期待,但現在最受到大家重視的不是創作者本身,反而是透過媒體藝術和電子音樂而使用到的技術。但我相信隨著時間的推移,這些多媒體的藝術仍然能夠成為在地創意發展的泉源。

同時舊有的創作形式和假設的新浪潮也透過一些活動進行整合。杭州就是目前中國在音樂發展中最令人興奮的城市之一,無論是實驗搖滾、新的夜店音樂,或是更偏向前述「駭客」模式的聲音藝術。事實上,杭州從來不缺乏人才,知名創作者李劍鴻就曾在杭州發展,而杭州具備繁華、地理位置靠近上海,而且是中國美術學院所在地等因素,這些都是對這個城市發展音樂有利的背景,只是過去杭州要維持穩定的音樂社群或經營穩定的觀眾群一直有其困難性。

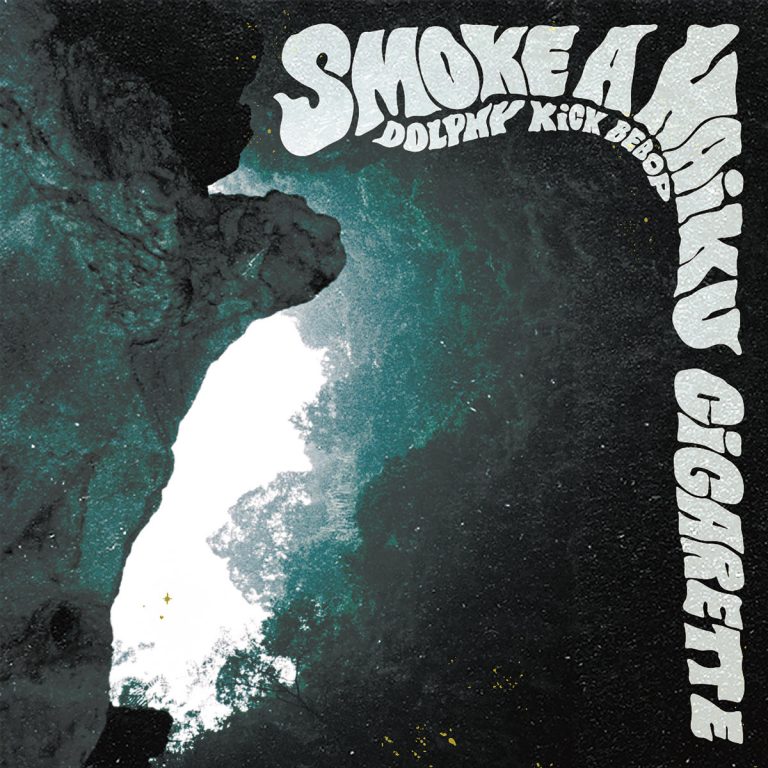

Dolphy Kick Bebop樂團是中國多年來最引人入勝的迷幻搖滾。他們的《Smoke a Haiku Cigarette》專輯於2018年6月6日,由Spacefruity Records發行。

Dolphy Kick Bebop樂團是中國多年來最引人入勝的迷幻搖滾。他們的《Smoke a Haiku Cigarette》專輯於2018年6月6日,由Spacefruity Records發行。

談到吉他音樂,Dolphy Kick Bebop樂團是中國多年來最具有說服力也最引人入勝的迷幻搖滾。他們的特色是密度很高的吉他獨奏和嘈雜的薩克斯風。2018年夏天,他們在Spacefruity唱片公司發表了《Smoke a Haiku Cigarette》專輯,這個唱片公司是由北京音樂演出場地fRUITYSPACE所經營的,而fRUITYSPACE被認為是北京最好的現場音樂演出場地之一,儘管它的音響系統非常安靜,但這裡仍是北京音樂社群重要的中心。這張專輯在浙江義烏市的某個叫做「隔壁」(Gebi)的場所錄製,義烏市昔日並非是以文化著名的城市,反而是以龐大的批發市場為其特色,在這樣的環境下義烏市居然存在著一個特別的錄音場所,就可看出中國音樂環境的變化。

夜店音樂的前線有新生代電子音樂廠牌FunctionLab竄起,這是年輕製作人Juan Plus One、GUAN、XHANKONKON和Yung Min(實際上在南京)所組成的團體。他們在派對上擔任DJ,並且在網路上發表音樂作品,靈感來自工業音樂、碎拍(breakbeat)、經典銳舞(rave)文化和當代夜店音樂。雖然FunctionLab顯然受到目前流行的後網路時代電子音樂的影響,但要將他們的音樂放到音樂分享平台SoundCloud和線上廣播社群來理解感覺更難。與其說是希望創作某種聲音潮流,不如說這個廠牌的音樂美學更像是幾個朋友間分享的音樂。

FunctionLab和另一個電子音樂廠牌play rec有共通之處,但創辦於上海的play rec是較為嚴肅的學術唱片公司,其共同創辦人之一的王長存曾是杭州中國美術學院的講師,另一位創辦者徐程則是上海噪音團體「虐待護士」(Torturing Nurse)的創始成員,而play rec品牌的音樂系統是屬於挑戰電腦音樂的新類型。王長存和徐程屬於中國實驗音樂和聲音藝術中較為成熟的一代,但play rec仍為年輕藝術家透過自造空間和新創企業中習得的技能創造出的成果提供了一個很好的範例。

提到杭州,當然不可能不提到其音樂演出的重要場地「噜噼」(Loopy)。噜噼出乎意料地位於一個購物中心內,但卻是擁有Funktion-One音響系統的黑盒子演出場所,並附帶咖啡廳/酒吧空間,提供高水準的西班牙小菜和義大利麵。噜噼不管是針對來自柏林的DJ巡演,或是當地另類搖滾樂團的演出,都能提供同樣出色的聲音品質。

_Loopy提供-768x574-1.jpg) 杭州重要的音樂演出場地「噜噼」(Loopy)。圖/Loopy提供

杭州重要的音樂演出場地「噜噼」(Loopy)。圖/Loopy提供

杭州雖然聚集了一些有趣的音樂家和藝術家,但他們在幾年前的重要表演大多發生在上海和北京,在杭州頂多只能舉辦一次性的藝術節和活動。如今這種情況已經逆轉了,杭州擁有中國最好的展演場館,而北京的表演者則要面對不完美的酒吧和夜店,或者更加混亂的臨時場地。

這並不是說杭州的音樂家是中國地下音樂的救星――杭州的情況極可能很快會改變――但是這個城市提供了一個案例研究,說明北京(和上海)以外的地方有什麼樣的可能性。下一批聚集類似動能的藝術家可能來自成都、廣州、深圳、廈門或福州。對這些藝術家來說,情況和十年前已經不同,他們不用透過到北京表演來「證明自己」。

首都將以某種方式持續存在,但它將不再是中國地下音樂唯一的定義。北京缺乏可靠的音樂展演場所,也許不僅是商業考量或為了保持某種特定的美學導致,但中國的地下文化活動能在地理位置的發展上更為分散是值得肯定的。即使大眾對北京的注意力會因此轉移,但實際上這可能反而讓更多有趣的事物在北京發生:不需要宏偉的敘事和自我宣稱的重要性,這個城市可以建構一個新的故事。