The fifth event of the series “Afterimage of History: Photography History Narrative Workshops” organized by Voices of Photography in collaboration with C-LAB invites Yumi GOTO, the founder of multifunctional photography-focused project space “Reminders Photography Stronghold” in Tokyo, to deliver a “Visual Narrative Bookmaking Workshop.” In the workshop, GOTO leads photography practitioners to explore how one or multiple narrative structures can be created through the use of images.

Yumi GOTO started the series of bookmaking workshop “Photobook as Object” in Tokyo in 2014 and “Masterclass” in 2015. “Photobook as Object” invites participants to bring their photographs intended for their books, to share how and in which context the mages are created, to discuss possibilities of photobooks, and then to make sample books. On the other hand, “Masterclass” is a collaborative project with an experienced Dutch graphic designer couple, Teun van der Heijden and Sandra van der Doelen, who both specialize in photobooks and photography exhibitions. Participants are asked to have a comprehensive proposal for a photobook ready that is to be carried out during the workshop.

The event at C-LAB this time, taking place for eight days, is more like “Photobook as Object.” Participants use images as departure points to weave together threads of messages conveyed by photography, including the subject, style, and color of a photo. They then collage images with other non-photographic materials such as documents, maps, poetry, or even some paper notes with random words. From what is gathered, GOTO assists participants to picture the story and construct a feasible blueprint for a narrative.

During the process of arranging photos, the development of a narrative is like the proceeding of a slow prelude, unfolding gradually through images. With discussions and debates with GOTO over and over again, creators try to get a hold of every element of bookmaking and attribute meanings to each detail: the material, texture, ink absorbency of paper, as well as how a book is flipped through, how it is bound, and the choice of material for the book cover. This multilayered complexity of materiality contributes to further complications, elaborations, and transformations of meanings of photobooks.

In the interview, Yumi GOTO shares with us how she steps into the world of photobooks and starts to organize workshops in Japan. We also get a glimpse of her views on photobooks, her aesthetics, and, how, via hand-made books, readers and bookmakers alike are able to be part of the (physical and psychological) journey through which photos come into being, and further become more aware of what’s happening around the world.

Firstly, could you please talk about how the bookmaking workshops began?

Yumi GOTO (GOTO):I have officially started photography relevant events in 1994. My husband is a professional photographer. Even though I am not professionally trained, I get to learn a lot of techniques while helping him. One can pretty much say that I have taught myself a great deal of knowledge about photography.

During this journey, I realize that knowing photography and showing photographs are two different matters. My husband is good at taking photos, yet he doesn’t know how to present his works in a well-thought manner. His works, however, need to be well presented to make sense particularly because they address social issues. I then start to help him show what he shoots in various forms. That’s why I work on photobooks and curating in the first place.

As I keep learning from practice, I also notice photographers other than my husband share this similar struggle: they don’t know how to present their works. So I help other photographers too. Although I start off as an amatuer, I have gradually gained considerable experience through collaboration with different photographers, with us editing photos and curating exhibitions together a lot. So far I have assisted a huge number of projects to their completion, most of which address social issues. These projects have to engage the public; they have to be well documented and preserved as well. Nevertheless, when photographers and I try to convey the message to an audience via photography works, we are aware of the existing limitations to a certain extent. What those photos have to say is not fully fulfilled in their presentation forms. We then experiment with various mediums and methods of presentation, including adjusting exhibition formats and finding other platforms to show photos, yet we still feel rather limited.

It was not until 2013 did I meet Jan Rosseel in the Hague, the Netherlands. At that time, Jan was studying at the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague (KABK). He had just finished his degree work Belgian Autumn. Although it was quite common to present a degree work in the form of a photobook, not many people discussed the possibilities in the production and forms of photobooks, whereas Jan had given quite some thoughts about it. He shared his ideas about potential developments of photobook-making with me. I was impressed and moved upon seeing what he created.

In Belgian Autumn, Jan documented several robberies and murders that happened in supermarkets in Belgian in the 1980s. 28 people died of this series of violent incidents, one victim among which was Jan’s father. In order to make this photobook, Jan had to carry out a thorough investigation of the incidents. Information about his father’s death was part of what he could easily know. The photobook included investigation results and new photography works based on the results. The incidents happened in the 1980s, a time to which he couldn’t go back and take photos at the crime scenes. However, he tracked down the locations of the incidents, revisited them, and took photos there. Since I had been thinking and exploring alternative ways for photos to convey a bigger picture, Jan’s approach provided a possible long-awaited answer just right to my questioning. When I saw the book, I knew that is what I want.

Luckily, Jan was intending to visit Japan. We then decided to organize a workshop together: the first bookmaking workshop in 2014, “Photobook as Object.” This workshop later became an annual event happening in May each year in Tokyo. Last year, we brought it to Latvia and attracted around 100 participants. As for “Masterclass” which started in 2015, we invited graphic designer Teun van der Heijden, who designed Jan’s photobook, to lead participants into in-depth consideration regarding the production of photobooks.

Among these workshops over the years, the first year attracted only Japanese participants, whereas many foreign participants joined in the following years, including those from Peru, Hong Kong, or China. This time in Taiwan, there was also one Taiwanese participant who had taken “Masterclass” in Japan before. I am hoping the participants of this event would have the opportunity to join our class in Japan in the future. Through international exchanges, the circle of photography and photobooks would grow bigger and bigger.

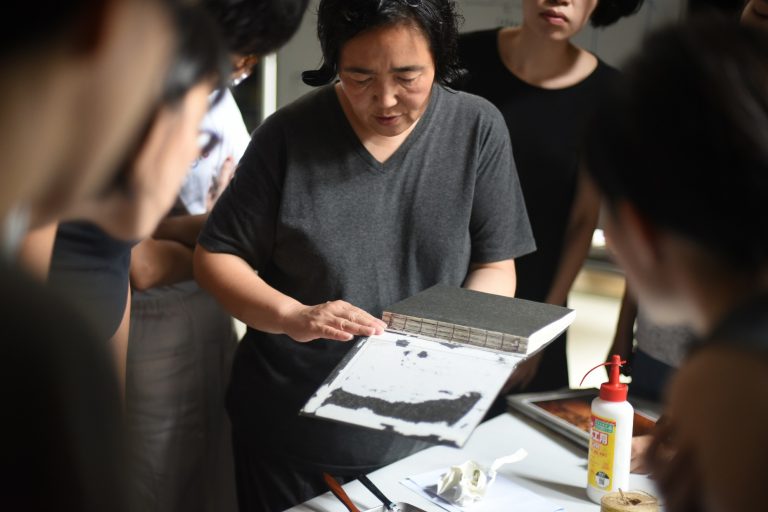

Yumi GOTO delivers the bookmaking workshop at C-LAB and leads Taiwanese photography practitioners to share how and in which context images are created, to contemplate over possibilities of photobooks, and to make sample books. Photo provided by Voices of Photography

Yumi GOTO delivers the bookmaking workshop at C-LAB and leads Taiwanese photography practitioners to share how and in which context images are created, to contemplate over possibilities of photobooks, and to make sample books. Photo provided by Voices of Photography

With discussions and debates with Yumi GOTO over and over again, creators try to get a hold of every element of bookmaking and attribute meanings to each detail. Photo provided by Voices of Photography

With discussions and debates with Yumi GOTO over and over again, creators try to get a hold of every element of bookmaking and attribute meanings to each detail. Photo provided by Voices of Photography

The workshop in 2014 is named “Photobook as Object.” Is there any particular implication of this title? In English, an “object” could mean a “goal” as well as an “object (as in philosophy in contrast to the term subject)” or a “thing.” Is it relevant to your views on photobooks?

GOTO: The word “object” involves “haptic perception,” meaning the feeling and understanding arising from the act of touching. Through caressing and touching objects, feelings also ripple through the inner sensitivity. Texture is not merely about materiality. It is, moreover, about palpability at a mental level.

Let me make an example. There is a photobook whose narrative centers around an old lady who lost her leg in the Bombing of Osaka. From her recent photos, we can see her uncovered prosthesis sticking out of her pant leg. Yet in her elementary school graduation photo, a crease on the lower part of the photo is noticeable—after losing her left leg, for a long time, she folded away parts of photos where other people’s legs are shown or drew upon her revealed deformed leg with black ink. She wouldn’t admit, nor would she want others to notice her deformity. The creator of the photobook uses the arrangement of photos and the preserved creases and stains, in order to allow readers to share this prolonged psychological journey with the subject when they approach the images. This is what I call haptic perception.

Often times, when we discuss the tragedy of the Second World War, we talk about how many houses were destroyed, how many people died, and how many were orphaned. These big numbers, however, consist of innumerable individuals. And everything every single individual has been through and suffered from during this war is what I would like to convey via the means of photobooks.

The creator purposefully preserves the crease at the bottom of the photo while making the photobook, which allows readers to feel the image and share the psychological journey with the subject. This is what Yumi GOTO called “haptic perception.” Photo © C-LAB

The creator purposefully preserves the crease at the bottom of the photo while making the photobook, which allows readers to feel the image and share the psychological journey with the subject. This is what Yumi GOTO called “haptic perception.” Photo © C-LAB

Such as the rough texture of the book cover, the use of different threads in the pages, and choices of special kinds of paper—all are relevant to what you called haptic perception which speaks correspondingly to the inner state of the subject?

GOTO: Yes. Instead of saying these design details are for technical concerns, we can say that they serve to embody the inner landscapes of the subject. The material chosen for the book cover also carries a message. For example, using fabric to make the book cover implies associations with tailoring, a stay-at-home occupation for those who weren’t able to go out to work because of their deformed bodies after the war.

As we mentioned earlier, “Photobook as Object” began as a collaborative project because of your encounter with Jan. Do you share similar opinions regarding photography and techniques of producing photobooks?

GOTO: Frankly speaking, our views are not perfectly aligned. After all, we only work together once a year during the annual workshop. Of course, Jan’s photobook resonated with me strongly when I first met him. When we are leading the workshops, however, it’s unavoidable that we have conflicting opinions and different focuses. Compared with him, I put much emphasis on narrativity, such as why a creator chooses a certain narrative technique, how he/she keeps developing the narrative with it, etc. I also care about accuracy. A creator has to know what he/she precisely wants to get across instead of a mere vague feeling or impression. That is to say, a creator needs to be able to explain what purpose each detail serves in the book accurately and persuasively when producing a photobook. I will also keep questioning creators: why is there such an arrangement? What can you achieve or do with these curated details? A creator has to know with clarity what he/she wants to express.

You mentioned narrativity. On the market, however, there are a lot of photobooks that focus purely on the layout of photos, or presenting photographs in abstract forms. Why do you emphasize so much on the narrativity of a photobook? You said in a previous interview that photos are not able to completely reveal the context of an incident which in itself is usually very complicated. Is this why you particularly focus on narrativity?

GOTO: To merely make a photobook is very simple. Taking photos is easy. Arranging photos is not difficult either. To make it a bit more complex, one can easily use photos to form another image or pattern. A piece of cake. Yet who wants to read such works? There isn’t always supposed to be a story or a narrative for a photobook, but there must be a precise conception, even for abstract works – we can say exactly because they are abstract, a clear conception is even more crucial. Creators can thus avoid blindly taking photos without any clue.

Contrary to image, narrative itself is indeed much more intricate. Readers can hardly understand the antecedents and consequences of an incident from what appears to be. Therefore, what we are doing is to visualize or materialize a deeper, more complex dimension in the presentation for readers. Creators don’t necessarily have to express himself/herself in a direct manner. It can be an abstract representation. Nevertheless, they must know what they are getting across to readers. Even if readers don’t get it while reading the finished products, creators can explain with definite confidence that every detail in the book means something – albeit the abstraction, works should be solid and should illustrate the inner states of creators.

Yumi GOTO is particularly interested in family histories. During the exploration of related issues, she reminds participants of the importance of research and addresses how unique investigative journeys contribute to the authenticity of a work. Photo provided by Voices of Photography

Yumi GOTO is particularly interested in family histories. During the exploration of related issues, she reminds participants of the importance of research and addresses how unique investigative journeys contribute to the authenticity of a work. Photo provided by Voices of Photography

In the workshop, participants have to discuss and examine every element of bookmaking over and over again, in order to figure out what they want to say, and to create a solid representation of their inner states. Photo provided by Voices of Photography

In the workshop, participants have to discuss and examine every element of bookmaking over and over again, in order to figure out what they want to say, and to create a solid representation of their inner states. Photo provided by Voices of Photography

A large part of the photobooks you make is about family, history, and archives. Are you personally interested in these topics? How does it affect your choices of subject matters?

GOTO: I indeed have a strong interest in social, political and historical issues. This is why I particularly endeavor to work on family history. No matter how grand an issue is, it consists of many individuals. Take the Japanese Peruvian who participated in a previous workshop as an example. He makes photobooks to document his family history. When his works are put into a wider social context, what he addresses is actually part of the history of immigration.

I also remind participants that when approaching these issues, their research relevant to the issues should take up to 80% of the creation. In order to give a bigger picture, photobook-making should not be limited to one kind of material. Besides images, documents and notes which help illustrate the narrative more comprehensively are to be used as much as possible.

The reason why I emphasize much on research is that while a creator engages in investigation, he/she naturally gets in touch with people. It can be asking for information or interviewing people to gain an in-depth understanding of an incident. Via interactions and numerous unexpected encounters, a creator gathers information on and of his/her own. Such an irreplaceable investigative journey contributes to the authenticity of a work.

What needs to be stressed is that this is not exclusive for highly talented people. Everyone can do this – every individual possesses something truly unique to himself/herself.

For Yumi GOTO, making photobooks and curating a photography exhibition are the same: there are topics, contexts, consideration for an audience, and an aim to help people recall their memories—the reason why she named the project space as “Reminders.” Photo provided by Voices of Photography

For Yumi GOTO, making photobooks and curating a photography exhibition are the same: there are topics, contexts, consideration for an audience, and an aim to help people recall their memories—the reason why she named the project space as “Reminders.” Photo provided by Voices of Photography

You mentioned at the beginning of the interview that you get to know more about photography because your husband is a photographer. Are you also interested in practicing photography? In addition to making photobooks, do you also try to create images?

GOTO: Although I am deeply interested in photography, I don’t really have a passion for creating images myself. Of course, like everybody else, I take random photos and upload them onto Instagram, but I don’t really dedicate myself to photography practice. When I work with other people to discuss how to demonstrate photography works, I feel I am a part of it with my wholehearted participation.

Since you teach participants to make photobooks, your role is like an editor and a curator. In your opinion, what are the differences and similarities between making photobooks and curating exhibitions?

GOTO: For me, they belong to the same category. “Reminders Photography Stronghold” also serves as an exhibition space. When holding exhibitions, we don’t simply show photography works. Instead, photographs are thematized and contextualized in exhibitions. The audience can be aware of the topic and respond to it. In this sense, organizing an exhibition and making a photobook are the same for me: there are topics, contexts, a curatorial process, and consideration for an audience.

You mentioned “Reminders Photography Stronghold,” a multifunctional photography-focused project space founded in 2012. Is it named as “reminders” because of the meaning of “reminding”? What kind of space do you intend it to be?

GOTO: “Reminders” indeed intends to take from the meaning of “reminding” or “helping someone remember.” People are forgetful. Images make those who remember the past keep remembering; they also allow those who have forgotten to remember again. The aim of founding “Reminders Photography Stronghold” is to help people recall their memories and think of things once important yet getting forgotten in the whirl of vicissitudes. In addition to exhibitions, we also have a library with a big collection of books. The second floor is our living space which offers accommodation for artists and writers. By living together, sharing daily life, and discussing social issues, we hope to inspire one another to think and reflect more.